"The Lone Wolf" AKA "The Creature from Cleveland Depths" (1962)

Preceding each story in The Night of the Wolf is a little intro that tries to link the four tales into a sort of grand narrative or episodic future history, and hammers home the book's main themes. In the intro to "The Lone Wolf," Leiber tells us we humans, in contrast to our cousins the apes, are homicidally crazy, and hide our insanity from ourselves "by inventing paranoid ideas like God." Fritz, you are supposed to show me, not tell me!

Fears of a Soviet missile attack have become so severe that most Americans now live underground! These subterraneans rationalize their decision to dwell beneath the Earth's surface with such convincing arguments as "It's a lot easier living in one room....You don't have to tramp from room to room hunting things."

Gusterson and his wife Daisy are still living above the surface with their three kids in their twentieth-floor apartment in Cleveland. A friend of theirs, Fay, comes up from the shelter city to visit every so often. Gusterson is a novelist and he is full of ideas, and Fay, who manages an "invention team" down below, often prods him for ideas for new inventions. Leiber is fascinated by the sexual charms of teenaged girls, as we have seen in so many of his stories, and one of Gusterson's ideas is a mask that can make an adult woman "look like a seventeen-year-old sexpot." Another of Gusterson's ideas is a portable reminder machine that will alert you of appointments and when your favorite TV show is broadcast and that sort of thing.

Over the next several weeks on successive visits Fay reports on the progress of these two inventions. The beauty mask is a disaster, as rioting teenagers have been using them as a disguise and the young actress used--without her authorization--as the model for the mask is suing the manufacturer. But the reminder device, dubbed "a tickler" (after what it is said secretaries would call the file of stuff they were supposed to remind the boss of), is a big hit with the government and other large institutions. The tickler sits on your shoulder and a little wire leads to a little earphone through which it speaks to you. The device can not only keep employees on schedule, but teach them their jobs and manage their labor, outlining every step of a process. Later models of the tickler manage morale via subliminal messages based on the mantras of Emile Coue, and even manage mood by intravenously injecting drugs into those who wear them. Gusterson worries the ticklers are graduating from becoming tools or servants to becoming masters, and goes down into the subterranean city to warn Fay--but he's too late! Below ground, he finds that the ticklers are already self-aware robots intent on self-preservation and that wearing one is already mandatory among the subterranean population and will soon also be required of the remaining surface dwellers!

The ticklers take over, and their leader, the tickler riding Fay, comes to Gusterson to consult him. The ticklers regard Gusterson as a sort of god or guru, he having "invented" them. Gusterson saves the Earth from robot tyranny by convincing the ticklers they should build spaceship bodies and divorce themselves from the slow and dim lummoxes that are humans and search the galaxy for a planet of their own.

"The Lone Wolf" AKA "The Creature from Cleveland Depths" moves at a brisk pace and is basically pleasant and intriguing, with all kinds of SF ideas and cultural references and some philosophical forays. While it does have horror and misanthropic elements its general tone is jaunty and light. Twenty-first-century readers will perhaps see some parallels between the ticklers and our ubiquitous smart phones. There are also plenty of Cold War references--to the Soviet Union and the fear it inspires, for example, and various missile tests and hypothetical weapons systems. I can moderately recommend this one.

"The Creature from Cleveland Depths" first appeared in Galaxy. The tale there is adorned with quite good illustrations by Wallace Wood (the robot is very fine as are the depictions of young ladies--hubba hubba) that spoil everything that happens in the story; the intro there stresses not that your religious beliefs are a paranoid reflection of your homicidal tendencies, but one of the story's themes, the distinction between the rare inner-directed man (exemplified by Gusterson) and the typical, outer-directed, man. Under its original title, which is far more appropriate (Gusterson has a good relationship with his wife and kids and tries to help his friend and the entire human race--he is in no sense a lone wolf) the story has appeared in a number of Leiber collections, including another one I bought in the same batch with The Night of the Wolf, You're All Alone, and several printed in foreign translation.

"The Wolf Pair" AKA "The Night of the Long Knives" (1960)

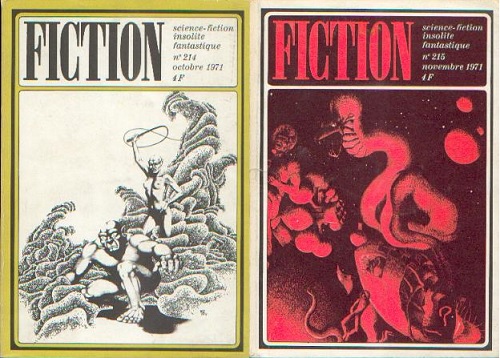

Under its original title, "Night of the Long Knives," which again is superior to the lupine title affixed to it here in The Night of the Wolf, this tale was an Amazing cover story. In 1971 it was split in two parts and serialized in the French magazine Fiction (here in The Night of the Wolf, "The Wolf Pair" is like 80 pages.)The intro to "The Wolf Pair" here in this collection indicates this story takes place in the same universe as "The Lone Wolf," but later, 20 or 25 years after a nuclear war that wiped out the subterranean cities and reduced most of the American countryside to a Deathland of radioactive dust. "The Wolf Pair" is a first-person narrative presented by a guy who wanders the Deathland, and describes to us in great detail the terrain of the Deathland and the psychology of the people like himself--Deathlanders are loners who don't talk, and who are driven by a powerful urge to kill all they meet--though sometimes the urge to slay is overwhelmed by the urge to fuck!

Among ruined gas tanks and electrical towers that Leiber waxes poetic in describing (the red light of the sky shows through little cracks in the gas tanks, forming a lace pattern), the narrator meets a woman with a hook for a hand and a radiation scar on her face--our hero finds the scar sexy, and the two, without speaking, go through the Deathlander ritual of laying down their arsenals of weapons to have sex. The narrator even removes his special razor-sharp dentures!

There are still a few civilized spots in North America, and an anti-grav aircraft from one of them makes an emergency landing near the two lovers and they appease the murder lust Leiber insists we all have in our hearts by slaying the pilot. A third Deathlander appears, an old geezer who is atypically voluble, and our narrator and his new girlfriend finally speak and we finally learn their names, Ray and Alice. The old guy they call "Pop."

(The cover of the British edition of The Night of the Wolf depicts Ray and Alice, but inexplicably suggests the story takes place in the United Kingdom.)

The trio pile into the aircraft to loot it of high tech devices and food, and then, dreaming it will take them someplace that wasn't ruined in the nuclear war, activate its automatic pilot system. The vehicle leaves the Midwest, where they are, and heads east. A voice addresses them; it turns out that the aircraft is carrying a precious cargo from one spot of civilization to another; these two high-tech areas are at war with a third. The voice convinces them to drop the cargo out the door at a specified point, though Alice is reluctant to and tries, unsuccessfully, to stop Pops from making the drop. Mission accomplished, the anti-grav vehicle carries them back west.

On the flight the three Deathlanders share reminiscences, unburdening themselves. Pops talks about how he is a member of Assassins Anonymous, a group of Deathlanders who have killed but want to stop killing. (In this story Leiber not only puts forward his theory that we humans are hardwired to be murderers, but the idea that killing is addictive, that our desire to kill is like the desire for booze of alcoholics or the need to gamble of compulsive gamblers.) Alice tells the story of how she was raped by the gang who killed her father and eventually got her revenge on them. And Ray, our narrator, reveals that twenty or twenty five years ago he was an officer in the United States Air Force and pushed the button that sent a flight of ICBMs to Moscow. (Buttons are a leitmotif of this story; the aircraft is full of buttons--there are no control levers or knobs or anything, just buttons--and that precious cargo Pops tossed out the door was a box full of little cubes with buttons that Ray presumes are some sort of grenades.)The automatic aircraft returns them to where they murdered the pilot. Pop figures out what the pilot was up to and what the cubes are--the cubes are hypodermic needles that can cure a plague that was running rampant in the civilized city to which they delivered most of the cubes, while the pilot had made an unauthorized stop to administer a dose to his girlfriend, who was staffing a one-man secret base hidden among the gas tanks. Our cast finds this poor plague-infected woman and Pop gives her a dose he pocketed before releasing the box out the aircraft's window. Their adventure, particularly the chance to talk over their experiences in the confined space of the aircraft, has inspired in Ray and Alice a desire to reform, and they join Pop and Assassins Anonymous.

While Leiber is confident we humans are inherently murderous, this story suggests he thinks that individuals can reform, can break their addiction to murder. The story also feels like an endorsement of Alcoholics Antonymous, and like something Leiber would write while working through his own feelings of guilt over some misdeed; perhaps it expresses his hope that he might be forgiven and learn how to behave. (Wikipedia does point out that Leiber was an alcoholic and had a close association with AA.)

"The Wolf Pair" is well-written on the level of individual sentences and is sort of shocking and throws a lot of philosophical and sociological ideas at you--it is ambitious and heartfelt and so certainly a worthwhile read. But is it fun, is it entertaining?

Though the story ends on a note of hope, it is bleak and depressing, and I had no sympathy or affection for the main characters--I was rooting for the doomed pilot when Ray and Alice were stalking him, and over the succeeding pages I kept hoping that our main characters would suffer some sort of punishment for their monstrous crime. I'm not the forgiving type, and I'm not the type to take seriously "who killed the Kennedys? Well, after all, it was you and me" arguments that society creates criminals, and I'm not the type to think the United States deserves any blame for the Cold War--I think burglars, muggers, rapists and murderers are to blame for the things that they do and that they should be severely punished, and I think the Communist Party of the USSR was to blame for the Cold War. I don't think crime and war are usually the result of psychological problems--I think most crimes and wars are the result of rational calculations of criminals and aggressors, calculations that are often severely flawed. So, I am not the intended audience of Leiber's story...or maybe I am the intended audience and I am just not finding Fritz's arguments persuasive.

Another issue with "The Wolf Pair" is the possibility that readers will feel Leiber goes overboard--Assassins Anonymous and razor sharp dentures so you can bite your victims to death are sort of silly, aren't they--and the passages about the urge to kill and all the strange behaviors Deathlanders engage in, like refusing to talk, are a little too extreme to be believable and even worse go on quite long and can be repetitious. The silly stuff in "The Lone Wolf" seemed to fit because the whole tone of that story was jocular, but the tone of this story is super serious, so wacky stuff that pops up sticks out like a sore thumb.

It has its problems, but I still can give "The Wolf Pair" AKA "The Night of the Long Knives" a moderate recommendation.

"The Wolf Pack" AKA "Let Freedom Ring" (1950)

Here's another story that debuted in Amazing and was presented as a two-part serial in the French periodical Fiction. "The Wolf Pack," which more often has appeared as "Let Freedom Ring," rehashes some of the elements and themes we just saw in "Crazy Wolf" AKA "Sanity," and, according to the little intro that precedes it, takes place some time after that story, when the system of diagnosing people's insanities and slotting them into appropriate jobs has broken down.For 200 years there has been no real war, economic scarcity or outbreaks of disease--life is easy! But the lack of challenge, and the lack of opportunities to appease the death wish and lust for murder that dwells in every human heart, periodically lead to alarming spikes in suicide and murder rates and raise the specter of some kind of revolution and total collapse of civilization into barbarism! The solution to these social and political problems is war! But not a real war with fighting; after all, there are no material or ideological disputes to trigger conflict and no foreign enemies to fight against. Instead, every two or three decades, a bogus "war" is conducted, in which the world government just drafts 5% of the population of young men at random, and spends vast amounts of money and resources building a huge armada of unneeded warships. After a few months of pointless training the randomly selected fighting men board the warships and sail to some arbitrary point where the ships self destruct and all the draftees are slain! The sadness of those families who lose a son, the relief of those who don't, and the atmosphere of fear and death and hardship generated by the human sacrifices and the waste of resources on mountains of unnecessary military equipment and supplies, reduce almost to nil the suicide and murder rates and unite the public, preserving order.

As the story begins, a new one of these fake wars that will kill millions of young able-bodied conscripts (and a small group of women volunteers!) has been declared.

"The Wolf Pack" is like 65 pages, and the narrative is in the third-person omniscient, and we see the story from the different vantage points of numerous characters, none of whom is interesting or likable. Some sections focus on a young man, Norm, who is one of the unlucky one in twenty eligible men marked for sacrifice. Some star the chief executive of the world government, a guy who, like the chief exec in "Sanity," is a 20th-century history buff. He and his inner circle of advisors have come to believe there is a secret underground working against them, endeavoring through subtle and sneaky means to "cure" the mental illnesses the underground believes the top government officials suffer from (each minister has a particular mental issue--one guy is obsessed with chess, for example.) Some sections foreground individual members of the administration, others describe the plotting and meetings of the members of the underground of would-be psychiatrists dedicated to giving therapy to all of humanity. This underground has come to the conclusion that they must stop the current war; they are convinced that if they can't succeed in curing the insanity of the human race this time, they never will.

Norm flees his home when he is shaken by the realization--in the only good scene in the story--that his family members are a bunch of government-loving sheep who truly think he should accept being sacrificed. In the crime ridden parts of town, he meets a "trim" pretty girl (Leiber refers to her repeatedly as "elfin") who is a member of the psychiatric underground. She enlists Norm into the underground, and he returns home to join the suicide army as their spy. The "war" effort is sabotaged and public morale undermined so effectively by the underground that the prosecution of the war is in doubt--the chief executive boldly responds by volunteering to join the doomed fleet on the day it is to set sail, and "volunteering" all his top minsters to join him! Norm is an officer on the flagship of the doomed fleet, and meets the chief exec and the man's great charisma tests Norm's loyalty to the underground.

The story ends very unsatisfyingly, with the leaders of the underground short-circuiting the suicide mission of the fleet by using their many devices and tactics, apparently including telepathy, and their encyclopedic knowledge of the particular mental problems of individuals, to drive everybody totally insane so that they fight each other, scatter, take off their clothes, whatever, rendering them unable to detonate the explosives that will annihilate the fleet. I guess it furthers Leiber's point that the human race is hopelessly irredeemable that the underground, which was trying to achieve its goals by curing people surreptitiously, resorting to exacerbating everybody's insanity when it seems the resourceful chief executive has foiled their Plan A.

There is a lame surprise ending, which has been foreshadowed several times, and seems to have little to do with resolving the plot--the chief exec's particular insanity is that he thinks he is Abraham Lincoln. Maybe we are supposed to think that a global civil war is going to break out (as the insanity outbreak of the fleet spreads to the entire world) and he will be a good leader who will help bring the civil war to a satisfactory conclusion? I don't really get it.

Of the four stories in The Night of the Wolf, the experience of reading this final story, "The Wolf Pack," was the worst. For one thing, after reading 150 pages about how all people are insane, reading another 65 pages of the same stuff was kind of a drag. I think there is more to my disappointment than that, though--I think this story really is objectively the worst of the lot. "The Crazy Wolf" had the virtue of being short. "The Lone Wolf" and "The Wolf Pair" each had a marked and consistent tone that gave them a distinctive flavor--the former was sort of jokey and light-hearted, the latter unrelentingly grim--and each also had characters endowed with personality. "The Wolf Pack" is long and dull, with no atmosphere and no interesting characters; much of the story consists of dry depictions of strategy sessions or the inner deliberations of individual strategists, and the character interactions (like the leader being some sort of recreation of Abraham Lincoln, and Norm's girlfriend's brother being a member of the secret police) don't add anything to the plot or atmosphere.

Gotta give "The Wolf Pack" AKA "Let Freedom Ring" a thumbs down.

**********

The back cover of The Night of the Wolf suggests that the stories therein are an attack on "militarism" that encourage people to be peaceful and that Leiber is a voice of sanity in our insane world. I think we can quibble that "militarism" and "urge to kill" are two different, though I suppose somewhat related, things. A more substantial complaint about the back cover text is that The Night of the Wolf doesn't really seem to offer any solutions to the problems of war and widespread insanity, but just to bemoan them. Rather than "an ironic encouragement to the peace of the world," what the book actually is is unbridled misanthropy and hopelessness, a series of variations on the old saw that "man is wolf to man" that argue that humans are essentially insane--irredeemably murderous and suicidal and addicted to the scam that is religion. Individual stories may have elements of hope, but the linking introductions seem intent on quashing any hope.

Maybe we can't blame Fritz for the text on the outside of the book, but perhaps we can blame Fritz for the effort to shoehorn these stories into a single narrative with those tendentious introductions, an effort which is a failure. The intros actually undermine the book as a whole, robbing the stories of nuance and surprise and puzzling the reader by referring to a "League of Sanity" that doesn't actually appear in all of the stories and, when it does, doesn't go by that name as far as I can remember.

I think we have to consider the possibility that crafting a collection of stories which all have the same theme and make the same argument is inherently a risky proposition, because reading them can get monotonous. Luckily, three of these stories are not bad.

**********

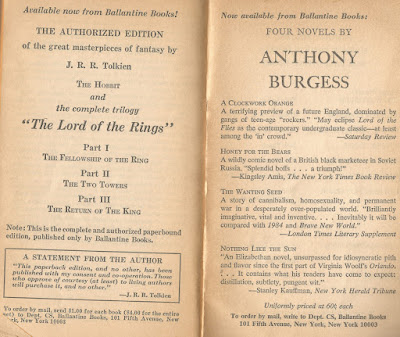

|

| Squint or click to read J. R. R. Tolkien's dissing of the first American paperback editions of The Lord of the Rings |

I read FUTURE TENSE when it was first published in 1964. Like you, I love the Powers cover! And, the stories are great, too!

ReplyDeleteNice haul from Wonder Book and Video, sounds like your car came away from that parking lot with its catalytic converter, oil pan, and CV joints, all intact.....?!

ReplyDeleteYour fortitude in reading FOUR Lieber stories from 'the Golden Age' is impressive...........I will avoid 'The Wolf Pack' at all costs.

There is nothing in The Night of the Wolf to match "Lean Times in Lankhmar," "Ship of Shadows" or "The Button Molder," but the first three stories in the collection have their virtues. And we should be hitting up old Fritz again soon here; maybe we'll come across another gem.

Delete