'What I was told made me very unwell. I don't get my promotion. My father's philoprogenitiveness disqualifies me. And my own heterosexuality.'

|

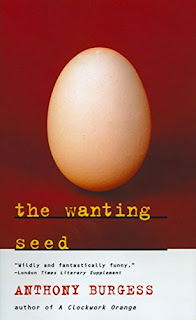

| My copy, front. Focus: cannibalism, terror, mind control (?) |

Beatrice-Joanna Foxe is a romantic, an atavist, an Anglo-Saxon heterosexual in a multi-ethnic future London of hundred-story tall skyscrapers, capital of a socialistic Britain dominated by gay men and eunuchs. Beatrice-Joanna has a voluptuous body, even though skinny girls are in fashion. She wants to be a mother even though reproduction is considered declasse by most members of her (middle) class ("Leave motherhood to the lower orders," she is told by a government bureaucrat, "like nature intended.") She believes in God even though she has never seen a Bible and religion has been largely suppressed. And despite all the government propaganda pushing homosexuality, she has an insatiable desire for men, while such common sights as that of lesbians kissing and of perfumed men applying lipstick make her retch.

Part One of the 223-page novel chronicles a single, terrible day in the rocky marriage of Beatrice-Joanna and her husband, Tristram. Tristram is a teacher of history, who, after completing the day's lecturing (Burgess uses the lecture to key us in to the novel's background and themes) is told that a gay man has been given a promotion Tristram himself was in line for because of Tristram's disfavored sexual orientation and because research indicated Tristram's parents had a shockingly large number of children (four.) For ages all government policy has been aimed at discouraging reproduction, but as the level of population threatens to overwhelm the ability of the Ministry of Agriculture to produce enough food to feed everyone, even on short rations, the authorities are cracking down harder than ever.

That very same day Beatrice-Joanna learns their infant son has died--public officials assure her it is for the best: "Think of this in national terms, in global terms. One mouth less to feed." While Tristram takes to a bar to look for comfort for the loss of his promotion in the bottom of a glass, his wife is comforted by Tristram's brother Derek. Derek, in reality a virile heterosexual who has been cuckolding Tristram behind his back, has for many years been putting on an extravagant and convincing imitation of a gay man in order to get ahead. And get ahead he does! When, as part of the crackdown, a new police force (the "Population Police") is formed, Derek is made its Commissioner!

|

| First edition, focus: skyscrapers and/or bar charts (?) |

(I'm not sure if we are supposed to take this cyclical theory seriously, or Burgess means it as a satire of mechanical Marxist and Whiggish theories that argue history is a kind of inevitable journey through various stages to a particular end point.)

In Part Two Beatrice-Joanna flees London for the countryside after discovering that she was impregnated (by Derek or Tristram, she is not sure) on the day her first child and Tristram's career hopes died. At State Farm NW313 she reunites with her sister Mavis and Mavis's husband Shonny, a man of unshakeable (or so it seems!) religious faith. For his part, Tristram gets mixed up in a street fight between striking workers (their gripe: rations have been cut again!) and the grey clad regular police and is tossed in prison.

In Part Three we briefly meet the Prime Minister, Robert Starling, and his catamite, Abdul Wahab. Starling is under terrible stress because a worldwide famine is leading to starvation and even cannibalism, and there seems to be no solution to the problem. Little Wahab is a Muslim and his naive (or is it cunning?) talk about the efficacy of prayer starts a chain of events in the government that leads to a lifting of prohibitions on religion. While Beatrice-Joanna is secretly giving birth to twins in an abandoned outbuilding on State Farm NW313 and underground clergymen are emerging from obscurity, Tristram, with the help of a Nigerian murderer and cannibal, escapes from prison.

|

| An earlier Ballantine, focus: reproduction |

Another aspect of an Augustinian Phase is militarism, and before he can get to his wife, Tristram finds himself shanghaied into the newly reactivated British Army! Part Five of The Wanting Seed is set a year into the new regime, that of George Ockham--all that anarchy only lasted a few days. While Beatrice-Joanna and the twins live in luxury (the new capitalist economy has improved living standards) with Derek (who has cast off his old nancy boy pose with the change in regime), Tristram, a sergeant, acts as an instructor to low-I.Q. privates, and then finds himself sailing off on a campaign. But, as the back cover blurbs of my copy warn you, the war is a sham: there is no war, and Tristram's platoon of dolts is simply murdered--this is the Augustinian government's solution to the overpopulation problem, to recruit the criminal and stupid and execute them, claiming they died defending their country.

In an epilogue, having survived the murder of his comrades, Tristram makes his way back to England and is reunited with Beatrice-Joanna. He also theorizes that the Augustinian period will not last long; soon the inevitable historical cycle will begin again.

|

| My copy, back |

As for being a novel about overpopulation, I didn't feel that Burgess was putting a whole lot of effort into developing an atmosphere of claustrophobia or impending doom, of describing how horribly overcrowded London was. It seemed to me that he was using overpopulation as an excuse to present his caricatures of Pelagian (leftist) and Augustinian (right wing) government, the former stifling people's freedom and natural inclinations and the latter indulging in gross violence and weeding society's losers out of the gene pool.

What I found more compelling than the overpopulation and strictly political themes was the novel's focus on love; as I read it, The Wanting Seed struck me as a celebration of heterosexual love, the kind of love that leads to the creation of children, the kind of love sanctioned and promoted by Christianity. I suppose I was primed to find such a theme in The Wanting Seed by my memories of A Clockwork Orange, published the same year as The Wanting Seed. In the final chapter of the original version of A Clockwork Orange (not the truncated American edition upon which Kubrick's film was based), Alex, after efforts of an overbearing and intrusive government have failed to reform him, is reformed by his own desire to have a child.

|

| A recent printing, focus: comedy |

While many of the religious characters in the book were silly or flawed, I still felt like Burgess was trying to put across a positive view of religion. Tristram, for example, follows a sort of Christian journey, learning to forgive his wife and to resist the (initially powerful) temptation to pursue revenge against his brother. The atheist characters in the story are not confident in their lack of faith, falling back into religiosity on slight pretexts, while, given the chance, the mass of people quickly reassert their belief in God, in the same way they enthusiastically embrace straight sex as soon as the Pelagian government falls. Burgess seems to suggest that a belief in God is as natural and irrepressible as physical desire for the opposite sex, that both are healthy urges that centuries of propaganda cannot extirpate.

The Wanting Seed apparently got good reviews when it first appeared, but if it was published in our 21st century I suspect the author would be at risk of being dragged before a court for the Michel Houellebecq / Mark Steyn treatment, not only for its portrayal of gays but for its attitudes about race. In the first dozen pages, as Beatrice-Joanna looks at a multiracial crowd, she reflects thusly:

Was it, she thought in an instant almost of prophetic power, to be left to her and the few indisputable Anglo-Saxons like her to restore sanity and dignity to the mongrel world? Her race, she seemed to remember, had done it before.As the novel presents heterosexuality as superior to homosexuality, and the pervasiveness of "homos" in Pelagian Britain as a source of disgust or horror, so too, I think, it presents the "native" British people as superior to the Africans and Asians who now make up the lion's share of London's population, and, as with gays and lesbians, suggests that the prevalence of nonwhites is a sign of an unnatural, unhealthy, cultural deviation. The widespread, government-sanctioned cannibalism of the Augustinian period, for example, is closely associated with non-white people--a cross-eyed "Mongol" at the labor strike voices his desire to have the police put in a stew pot, there is the aforementioned murderous Nigerian whom Tristram meets in prison, and when Tristram is in the army the soldiers' rations, he finds, are human flesh imported from China. While white British people and the government do embrace cannibalism, Burgess seems to be trying to suggest that it is a fundamentally alien practice, a foreign perversion which has infected the people of the sceptred isle.

I would expect many people nowadays to find The Wanting Seed's points of view reprehensible, and I have already suggested that it is too satirical for my tastes, that it did not elicit an emotional response from me. But the novel has its virtues and I am still happy to give it the old thumbs up--it is amusing and interesting.

|

| The final page of my copy advertises three Burgess novels, all of which I have read and can recommend |

Not a great novel, and not the shocking horror show advertised, but a good novel, readable, thought-provoking and entertaining.

No comments:

Post a Comment