Here at MPorcius Fiction Log we are reading stories by authors whose names begin with "S" that were published in 1958 and recommended by every New York newspaper's favorite SF anthologist, Judith Merril. Last time we read stories by Margaret St. Clair, Thomas N. Scortia and John Shepley. Today we've got stories by two big names in the SF world, Robert Silverberg and Clifford Simak.

"The Man Who Never Forgot" by Robert Silverberg

"The Man Who Never Forgot" debuted in an issue of F&SF with a story by Poul Anderson we read back in 2021, "The Last of the Deliverers," and stories we have yet to consume by Chad Oliver and Avram Davidson. [UPDATE 4/30/2025: Further research indicates I read the Avram Davidson story in question, "I Do Not Hear You, Sir," back in 2018. Oops.] Maybe we'll come back to this ish soon.I talk too much about how SF readers want to simultaneously be members of an oppressed minority and members of an elite with special powers--I just did it in my last blog post--but here we have another example. The protagonist of "The Man Who Never Forgot" has super intelligence and a super memory and this causes others to resent him, to make fun of him, to shun him. He leaves home in his early teens to travel the country, forging no long-term relationships as he moves from city to city, state to state.

Around age 30, by chance, he encounters his mother and realizes he has changed, that he has grown up--maybe he can have normal healthy relationships, build a family, contribute to the world. "The Man Who Never Forgot" has a happy ending, but one more like that of a realistic and mature piece of literature than that of a run-of-the-mill SF story--instead of resolving the plot by going on a campaign of revenge or leading a paradigm-shifting revolution that changes the world, the protagonist changes himself. Good advice for all you angry young men out there!

"The Man Who Never Forgot" is more like a character study then an actual story, and the plot just sort of resolves itself, but Silverberg's story is an engaging and smooth read nonetheless. Grade: the high end of acceptable.

Silverberg included "The Man Who Never Forgot" in the 1974 anthology he edited, Mutants, and it has appeared in a few other anthologies as well in addition to numerous Silverberg collections.

"Slice of Life" by Robert SilverbergThis baby debuted (under the Calvin Knox pseudonym) in the same issue of Infinity which offers a story by John Bernard Daley which we've already read, "Wings of the Phoenix," and a Clifford Simak story we are about to read. Merril was really into this issue of Infinity!

Here we have a story that questions the desirability of utopia and also romanticizes the figure of the great artist, and yet again depicts with sympathy the alienated young person who is superior to the common run of humanity. "Slice of Life" is about as good a read as "The Man Who Forgot Everything," but the plot works better because a main character faces a dilemma and must make a difficult decision.

It is the future! Not only is everybody healthy and happy, but everybody has empathic psychic powers and their ability to sense other people's emotions facilitates healthy human relationships. But little Danny, eleven years old, three years ago fell out a fifth-floor window and his leg bones were smashed to bits--he has been bedridden ever since--and lost his psychic abilities! Cut off from psychic rapport with other people, Danny has almost entirely stopped communicating with other people, and he doesn't read books or listen to music either--he just sits in bed all day and daydreams, just grunting in response to his parents' efforts to speak to him.

A therapist comes to visit Danny, hoping to cure his psychic disability. (Don't worry about his leg--this is the future and as soon as he is fully grown they'll saw that thing off and give him a robot leg.) The therapist realizes Danny has constructed an elaborately detailed dreamworld where he has adventures with a wide cast of characters. The headshrinker is astonished by how vivid and thrilling is the fantasy world Danny has conceived; Danny, he realizes, is one of the world's great artists! Such artists have been few and far between since modern society became as peaceful and stable as it is today, because the minds of great artists are generally some cocktail of unhappiness, ill-health, alienation, and perversion. The therapist thinks of Beethoven ("deaf"), Mozart ("a sickly pauper"), Leonardo and Shakespeare ("sexual deviates")--seeing as today there is no poverty, no physical illness, no mental illness, there are today no Beethovens, Mozarts, Leonardos or Shakespeares! The therapist is confident he can bring back Danny's psychic powers, but he is equally confident that if he neglects to cure Danny, the kid will become the greatest artist of the age and produce work that will delight millions! So he lies to Danny's parents, saying he can't cure the boy, but assures them that their son will grow into a great man."Slice of Life" has not been reprinted widely, even though Merril really liked it and I think it is fine; besides Infinity it looks like it only ever saw print in John Carnell's New Worlds.

"Leg. Forst." by Clifford Simak

So we move to the second "S"-man we'll be talking about today, Clifford Simak, and our second story today from the April issue of Infinity. I like Simak but his anti-city and pro-primitivism (people call this "pastoralism," I guess) attitude can get on my nerves. (I do not think the world would be a better place if all the humans except some Plains Indians died and the Earth was taken over by robots, intelligent dogs and intelligent ants.) Well, let's see if Simak is pushing some wacky line with this story, which certainly has a wacky title.It is about two thousand years in the future. The human race has expanded throughout the galaxy, and today has commercial relationships with untold numbers of alien civilizations.

Our hero is a widower who, following retirement from business as an interstellar importer/exporter (he was a pretty sharp dealer, he'll have you know) and the death of his wife, took up stamp collecting--with a passion! Over the last twenty years he has amassed a first-class collection of stamps from all over the galaxy as well as deep knowledge about the stamps of many nonhuman races, even though his only living relative, a nephew who himself is trying to make it in the business world, and his nosy neighbors are always trying to waste his time.

The plot of "Leg. Forst.," a story of almost forty pages, has many moving parts, but they all move smoothly together and make internal sense and all aspects of the plot are pretty entertaining. Even if the idea of stamps being used to pay for the shipping of documents and goods between solar systems is kind of silly, it and other SF concepts in the story are fun, and Simak's light and pleasant style carries you along and soothes away any desire you might have to pick apart the logic of the story.

To put it briefly, a series of coincidences involving traditional comic elements--a buttinski widow who is trying to seduce the stamp collector with her cooking; a woman who is scared by a mouse; an absent-minded old hobbyist whose apartment is an absolute mess of clutter and who is clumsy enough to spill broth on a rare stamp--leads to a world-wide paradigm shift when the stamp collector and his nephew accidentally revive, and then in pursuit of profit intentionally propagate, intelligent alien spores which can read minds and which have a passion for order. Employing their amazing telekinetic and telepathic powers, these spores not only render the physical Earth neat, tidy and efficient, but also the social and political Earth, compelling people to behave honestly and generously. The stamp collector, who has contacts all over the galaxy, enjoys access to an antidote to the spores' effects which will allow him to continue behaving selfishly when he feels like it, giving him a leg up on every other Terran.

Thumbs up for this fun and creative story. Maybe Merril liked "Leg. Forst." because it is fun, or maybe because it serves as a wish-fulfillment fantasy for leftists who dream of some deus ex machina power reining in business people and making the entire human race toe a line. Either way, a good choice on Merril's part.

"Leg. Forst." would go on to be reprinted in quite a few Simak collections.

"The Big Front Yard" by Clifford Simak This Astounding cover story won a Hugo, so has the endorsement not only of the idiosyncratic Merril but a sizable contingent of the active SF community. (We've already read a story from this issue of John W. Campbell Jr.'s genre-dominating magazine, Pauline Ashwell's "Big Sword," which we mildly recommended.)

"The Big Front Yard" bears some similarity to "Leg. Forst." There's the protagonist, a charming sort of rascal. And the aliens who help him out, unbidden and by surprise. And humans who seek to profit by the aliens' special abilities. And the ending in which Earth life is going to be irrevocably changed thanks not the the action of the government but relatively humble small business people.

Our protagonist is a handyman and antiques dealer in the upper mid west--people keep calling him a "Yankee" and implying a "Yankee" is a serious sharp efficiency-minded businessman who gets good deals by skillful "dickering." Simak also portrays the handyman as a good person who treats people fairly and loves his dog to death and would do anything for this beast, and as a man jealous of his liberties when it looks like the government is going to trample on him, and a man with a spiritual connection to his ancestral home. (This dude is alike an amalgam of stereotypes of the sympathetic American, or what Americans like to think of themselves as, at least before America became a nation of obese pot-smoking porn-addicts.)

Weird, but welcome, stuff starts happening around the house. For example, a black and white TV our hero was supposed to fix for the wife of the richest man in town gets fixed while he isn't looking and now can receive color images--images more clear than any color TV reception the richest man in town has ever seen. Moneybags owns a computer factory and wants to bring the TV to his factory to see if his techs can figure out what makes the improved TV tick so he and the handyman can get rich off this new technology.

The mysterious unseen aliens fix other broken stuff, and eventually construct a star-system spanning portal inside the handyman's beloved old house. The handyman, if he steps out his back door, finds himself in America as usual, but if he steps out the front door he is in a desert on an alien world.

This is a longish story and there are little subplots but the main thrust of the story is that the handyman, a man of business who loves to make a profit but who recognizes that good business is based on knowing how to treat people, proves better able to deal with the aliens who eventually show up (and are also serious but essentially fair-minded business people) than do the government people who invade the town when the world becomes aware of the portal, and, because the portal between worlds is on his property, and the only man available who can talk directly to the aliens is the local dimwit who happens to be a telepath (and whom only one man in town--the handyman--ever treated decently), the government people have to let the handyman take the lead in handling Earth's interstellar diplomatic and commercial efforts.

I like the story's ideology and its speculations on the nature of interstellar trade, and the characters and their relationships are pretty good, so even though the aliens themselves are a little too cutesy, thumbs up for "The Big Front Yard." When Simak soft pedals his pastoralism--just portraying small town people in a positive light and confining his attacks on city folk to government lackeys--his work is fun. A good pick by Merril and an understandable Hugo win (it beat Jack Vance's "The Miracle Workers," C. M. Kornbluth's "Shark Ship," Fritz Leiber's "Deskful of Girls" and Pauline Ashwell's "Unwillingly to School" among other novelettes I haven't read.) "The Big Front Yard" would be reprinted in many anthologies and Simak collections.

**********

I can't disagree with Merril's picks here, which is nice. We also might see these stories as good representatives of their authors' bodies of work. One of Silverberg's most acclaimed novels, Dying Inside, is about the psychological life of a psychic, his use of his powers and how it affects his relationships and how he responds as he starts losing his powers. (I read Dying Inside while I lived in New York, when my meat space life was interesting enough that I would never have started a blog, and I recommend it--I mean the novel, not just living in New York.) The Simak stories share the concerns of Golden Age science fiction (Simak started his career in the early 1930s) with paradigm shifts and new technologies and human interactions with aliens, while also forefronting the lives and relationships of simple (on the surface as least) "down home" characters and subtly attacking the elites in Washington and elsewhere.

Let's hope out next batch of 1958 stories by "S" authors is as comfortable as this one!

**********

"S" is only the latest letter in our long alphabetical march through the honorable mentions list at the back of the fourth of Judith Merril's "Best of" anthologies. Here find links to the previous stops on our campaign, those from from A to R.

Poul Anderson and Alan ArkinPauline Ashwell, Don Berry and Robert Bloch

John Brunner, Algis Budrys and Arthur C. Clarke

"Helen Clarkson" (Helen McCoy), Mark Clifton, Mildred Clingerman and Theodore R. Cogswell

John Bernard Daley, Avram Davidson and Chan Davis

Gordon R. Dickson

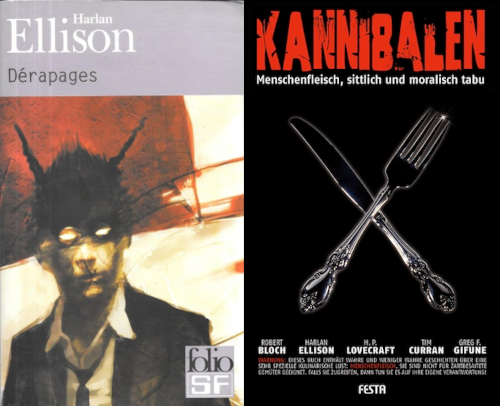

Charles Einstein, George P. Elliot, and Harlan Ellison

Charles G. Finney, Charles L. Fontenay, Donald Franson, and Charles E Fritch

Randall Garret and James E. Gunn

Harry Harrison, Frank Herbert and Philip High

Shirley Jackson, Daniel Keyes and John Kippax