Past the dinosaur-centric cover, an ad for a free camera ("you pay only for film and processing!"), and the table of contents, we come to Fred Pohl's editorial, which which eloquently bears witness to the vagaries of the publishing world. After making tepid jokes about how Jack Vance's house is high atop a San Francisco hill, Fred promotes the appearance of Vance's The Killing Machine in the pages of If starting next month--but it seems that The Killing Machine was never printed in magazine form anywhere. Fred also touts the appearance in this number of new author L. D. Ogle's "The Heat Racers"--in fact, "The Heat Racers" would be printed in the coming January issue of If. Fred also urges us to start attending SF conventions, saying that the recent convention in Berkeley, where guests of honor Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett, as well as Harlan Ellison and Forrest J. Ackerman, spoke, was a "first-rate affair"--on this matter, at least, I am sure Fred is not mistaken.

|

| This issue of If is full of embarrassing mistakes, printing errors, and typos |

"When Time Was New" by Robert F. Young

The first story in the issue, and the subject of Gray Morrow's cover illustration, is Robert F. Young's "When Time Was New." Consulting the records, it looks like I have blogged about five Robert F. Young stories here at MPorcius Fiction Log:"Thirty Days Had September"

"The Dandelion Girl"

"Ape's Eye View"

"Starscape with Frieze of Dreams"

I liked four out of five of those stories; maybe "When Time Was New" can make it five out of six.

If memory serves, "Thirty Days Had September," "The Dandelion Girl," and "Starscape with Frieze of Dreams" were about things like failing sexual relationships and baleful changes in society, while "The Ogress" (like Starscape...") had as one of its themes terrible violence. These were, for lack of a better term, "adult" or "mature" stories. In contrast, "When Time Was New" reads like a juvenile. The story can be saccharine sweet, is full of squeaky clean G-rated jokes, and when the main characters have to fight monsters or bad guys they never directly threaten their lives--they employ force fields, stun guns or luck out when the villains kill each other or blunder into a deadly accident.

The main character of "When Time Was New" is Carpenter, a guy who works for a 22nd-centrury institution that sends people back in time in robotic dinosaurs to investigate anomalies in the fossil record. While plodding about the Cretaceous landscape in his robotic triceratops (the horns of which are powerful stun charge projectors) he spots two kids hiding from an aggro stegosaur! He rescues them and learns they are from Mars, where, 79 million years ago, there was an advanced spacefaring human civilization.

These kids, Marcy (11) and Skip (9), were kidnapped and brought to Earth, and recently escaped their captors. While he drives them around, giving their pursuers (who fly robot pterosaurs) the slip, the kids tell Carpenter all about Mars and its totalitarian society in which the government raises all children and in your teens you have to take drugs that suppress your emotions so you will behave like a good logical citizen. Marcy and Skip are geniuses (Marcy can multiply two nine-digit numbers in her head faster than Carpenter can type them into his calculator and Skip is a whiz with machines) and so are very valuable to the bolshies that rule Mars with an iron fist.

Carpenter then camps out with the kids, and Young describes in detail how he tells them all about American history and how they eat hot dogs and roasted marshmallows and so on. Skip falls asleep and Carpenter tells Marcy all about the woman he has a crush on, one of his colleagues back at the North American Paleontological Society. Carpenter is shy and afraid to talk to his crush (he calls her a "goddess" whom he "worships from afar") and Marcy urges him to be brave and tell her of his love.

The kidnappers are defeated (by the prepubescent geniuses as much as by Carpenter) and Martian government goons arrive to take Marcy and Skip back to perform their duty to the state on the red planet. The triceratops robot got damaged in the struggle with the kidnappers, so Carpenter can't get back to the 22nd century, and the Martians don't want a guy with emotions mucking up their logical world so he is left behind to be menaced by a tyrannosaur.

The tyrannosaur, luckily, is a robot driven by Carpenter's colleagues, including the woman he has a crush on. He is rescued! And, Young using a similar plot device to the one he used in "The Dandelion Girl"--and reminding us of some of the shenanigans we see in Heinlein novels--Carpenter's crush turns out to be a grown-up Marcy, who so fell in love with him on their camping trip that she and Skip built a time machine under the noses of the Martian commissars so she could come to the 22nd century to marry Carpenter!

Young's heart is in the right place--of course I like dinosaurs and of course I hate Martian commies--but this story, which takes up over 30 pages of the magazine, is long and slow and sappy. At first, seeing as the female lead is a math genius who saves the day, I thought I might be able to recommend this story to the feminist community, but since Marcy performs her arithmetical wizardry and demonstrates her heroic perseverance in pursuit of a man (and is the only female character in the story, besides) I guess "When Time Was New" fails the Baldanders test and must be categorized as patriarchal propaganda.

Maybe I would have given "When Time Was New" a thumbs up as a kid, but I'm afraid today I have to give it a regretful marginal negative vote. In 1983 an expanded version of the story was released as the novel Eridahn.

(On a side note, the story references the 1869 poem "Darius Green and His Flying Machine" by John T. Trowbridge, a poem I had never heard of before but was perhaps (?) famous in 1964.)

"The Coldest Place" by Larry Niven

Here we have one of Niven's Known Space tales. In fact, it is the first published Known Space story. In fact--again!--it is Larry Niven's first published story! Just recently here at MPorcius Fiction Log we read the Known Space novel Protector, and in 2017 we read the 1965 Known Space piece "Becalmed in Hell;" back in the forgotten days of 2014 I read the Known Space story that debuted in Harlan Ellison's famous anthology Dangerous Visions, "The Jigsaw Man."The copy of December '64's If that was scanned and uploaded to internet archive is actually signed by Niven, which is fun. (Is this an opportunity for me to remind you that I own a copy of Alone Against Tomorrow signed by Harlan Ellison?)

"The Coldest Place" is more like an anecdote than a full story. The narrator, an astronaut, and Eric, the disembodied brain that runs the spaceship, go to Pluto to investigate the possibility that there is life there. They take a sample of a big mobile blob, unsure whether it is an amoeba monster or just helium reacting to the temperature conditions that prevail on Pluto in a way that surprises Earthers. The End. I guess the "arc" and surprise of the story are supposed to be provided by the hinting and then revelation that Eric is a disembodied brain, but Eric appears in "Becalmed in Hell," which I've already read, so I knew what to expect.

Acceptable.

"At the Top of the World" by J. T. McIntosh

Multiple times on this blog, and elsewhere online, I have subjected J. T. McIntosh to derision. (Is this an opportunity for me to remind you that many years ago The Onion quoted some of my withering attacks on McIntosh's The Million Cities?) In 2016, in my hostile review of Norman Conquest 2066, I even declared that I was through with McIntosh. And yet here I am about to read 16 pages of his prose. Why? I wonder myself.Gallery 71 is an underground city housing 53,000 people, a place which has no contact with the outside world and where the government strictly controls population and forbids all inheritance. The founding documents of the 200-year-old settlement instruct that at the two-century mark the inhabitants should dig straight up for five thousand feet. We readers know this is to discover if the radiation on the surface has abated enough that the people of Gallery 71 can leave their subterranean authoritarian state, but, like the passengers in a generation ship in so many SF stories who don't know they are in a spacecraft, the inhabitants of Gallery 71 don't realize there is a surface. To them, "Gallery 71" is synonymous with "the world" or "the universe."

Some people are willing to follow the inscrutably mysterious instructions of the Founders, others think the vertical tunneling too risky or a simple waste of time and want to ignore this inexplicable decree from the forgotten past. The debate gets so heated a riot erupts, and McIntosh gets to indulge in his penchant for sexualized violence by describing the bloody beatings and fighting that takes place; the beautiful daughter of the head of government has her blouse stripped off by an attacker and then her constricting skirt ripped off by a friend so she can run away to Daddy's flat.

The head of government authorizes the digging of the new 5,000 foot vertical shaft, revealing the surface and sky, to the amazement of everybody. Thirty young people, including the government head's sexy daughter, explore the surface for a few hours--they love the feeling of the sun on their skin and take off their clothes! They return inside as the sun sets and temperatures drop. The next day these troglodytes have painful sunburns and the government thinks that sunlight is the dangerous radiation the Founders warned of, and collapse the tunnel, much to the consternation of the young explorers, who try to convince the old people in government, without success, that you can protect yourself from sunburn just by keeping your clothes on. The final paragraph, however, vindicates the caution of the olds--an enemy aircraft spotted the kids yesterday, and today this unidentified enemy, still at war with the people of the Gallery 200 years after driving them underground, drops a radiation bomb where the shaft was opened yesterday, making the surface above Gallery 71 deadly to all life again.

J. T. McIntosh doesn't seem to know what he is doing when he writes these things. The sex and violence that so many writers use to add tension and excitement to their stories and to emphasize their points he just tacks on in a way that feels inorganic and encumbers rather than strengthens the story. For a while I thought J. T.'s objective with the story was to make more or less legitimate but totally banal observations about politics that everybody already knows or at least pretends to believe while they are burning down the police station or looting the department store: that mob violence is wrong, that old people tend to be cautious and young people tend to be adventurous, that a society needs both conservatives and risk takers because sometimes it makes sense to be prudent and careful and other times it makes sense to strike out across frontiers and do risky new things, that tradition can be a useful guide but some traditions eventually outlive their usefulness when circumstances change, etc. But what are we to make of the two twist endings that have the old people making a mistake that inadvertently preserves the Gallery from the commies or aliens or whoever operates the bombers? That we should always be super duper cautious? Or that life is a random chaos and whether we survive or expire is down to luck?

Perhaps a bigger sin than bungling whatever argument McIntosh might be trying to make is that his writing is lacking in feeling and personality. There is no fun or fear in his work because his writing style is so lame--even a scene of a young woman having her clothes torn off generates no emotion in the reader.

Thumbs down!

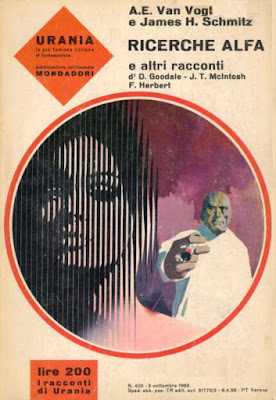

Our Italian friends were brazen enough (or negligent enough) to print a translation of "At the Top of the World" in a magazine with a characteristically terrific cover illo by Karel Thole. The issue is headlined by James H. Schmitz and A. E. van Vogt, whom I daresay are much better emissaries of English language genre literature than ol' J. T.

"Pig in a Pokey" by R. A. Lafferty

Here's a pretty straightforward, even traditional, SF story from R. A. Lafferty, a guy whose work is generally unconventional and often challenging to grasp. "Pig in a Pokey" does include the sort of gruesome violence and references to the American West we often find in Lafferty's work, however.Two people, a pig-like space alien and a human, have staked claims to an asteroid. The alien has secured his claim by killing an earlier human claimant via a cunning trick that leaves him safe from prosecution. The current human claimant also falls afoul of the trap, but figures a way out of it and turns the tables on the porcine alien.

The alien trap, which I won't describe here, is fun and interesting, and Lafferty's breezy pleasant style is enjoyable to read. "Pig in a Pokey" is the only story in this issue of If that I can recommend without reservation. Maybe it is slight compared to Lafferty's more crazy, more ambitious productions, but it works like a charm--I can't think of anything about it that should be removed and I can't think of anything that should be added, it is entertaining from start to finish.

"Pig in a Pokey" was included in the 1974 collection Does Anyone Else Have Something Further to Add?

In the middle of "Pig in a Pokey," in the center of the magazine, is an envelope and order form for those interested in taking advantage of holiday subscription rates for If, Galaxy, and Worlds of Tomorrow. These ephemera feature some pretty adorable science-fiction images of Santa Claus.

After the Lafferty story comes the conclusion of the Keith Laumer serial Hounds of Hell, which I am skipping, even though Emsh provided it with some pretty thrilling illustrations of monsters and office block-sized battle tanks. Hounds of Hell would be printed in book form under the title Plague of Demons, and maybe I'll read that version some day.There is also a heart-wrenching letter from a woman in Tacoma. She would like to join a club or discussion group of people interested in talking about SF and E.S.P. but the group has to be in Tacoma because she is "severely crippled" and has trouble getting around. Damn, I hope things worked out for this person.

(The letters column at If is an emotional roller coaster!)

At the end of the magazine is a full page ad for book plates, including two by Emsh, one of them featuring a slide rule, a circuit diagram, and a lot of other sciency stuff--I guess the SF fans of 60 years ago really knew, or aspired to know, about the hard sciences.

**********

I don't want to say this is a poor issue of If, because maybe the Laumer is good, and Emsh's contributions are certainly worth a look, but the two long pieces I read don't deserve a passing grade and only one of the short pieces, Lafferty's, merits a grade above "acceptable." Let's just say this was not Fred Pohl's finest hour, and he and Niven and Young would go on to do better things.

I do love the Grey Morrow cover! The 21st Century has so failed me! No flying car to go to the moon and no Triceratops time machine. Bet you get some respect in traffic with a 'dino truck! Oh, I have the same imaged copy and hadn't known about the Niven autograph before you mentioned. His handwriting is as sloppy as mine.

ReplyDeleteI'm guessing somebody brought this issue of If to a convention so Niven could sign it. It would be funny, and I guess brave and/or obnoxious, to ask Jack Vance to sign that ad for "The Killing Machine" by "Jack Lance."

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteThe danger of asking Jack Vance that question weighs in the balance of your belief in zombies. The Great Oracle says he left us in 2013. In 2016 I was doing a fan fic which referenced Vance, and someone told me he was still alive. HMMM! Perhaps they know something. . .

Delete(Sorry for the deletion-I had a garble in my dates. BTW, I'm from Iowa and I'm amused by your occasional noting of buying books here while on the road. FWIW, because of Alfred Bester's The Animal Fair, Rutgers is one of my favorite colleges I probably will never see.)

My wife is from Iowa and we lived in the Des Moines area for like 4 years. I made many great SF finds at Des Moines Library book sales, Half Price Books in West Des Moines, and even a church thrift store in Osceola.

DeleteAmazingly enough, we are currently on a road trip so it is not impossible I'll make some Iowa purchases in the coning weeks!

Very cool! I enjoy your reviews and spoilers don't bother me a bit.

DeleteThanks!

DeleteI ended up not buying anything in Iowa, but got some stuff in Ohio and Illinois that will soon turn up here on the blog.