"I loved you then. That was when I could still love. But you were right, Sandivar. It is a freezing of the soul. All laughter is frozen, and all love. What remains is death; but for my purposes, death is enough."Benjamin Leopold Haas wrote mainstream novels and nonfiction about the American South under the name Ben Haas, and paperback genre fiction, like sex novels and Westerns, under a variety of pen names, including three fantasy/SF titles listed at isfdb, all of which I own. I read Quest of the Dark Lady, published under the Quinn Reade pseudonym, back in 2015, and today I am cracking open the first book in Haas's two-volume Gray Lands series, The Sword of Morning Star, published under the Richard Meade pseudonym in 1969. I liked Quest of the Dark Lady, and with luck this novel, and its sequel, Exile's Quest, will be equally entertaining.

Our tale is set in what we today call Europe, thousands of years in the future, long after "the Worldfire," which is either a euphemistic term for a nuclear war or a catastrophic war between wizards that Haas is using as a sort of allegory for nuclear war. Mankind has been reduced to feudalism; most people are illiterate, men ride horses and fight with swords and are ruled by kings. Living alongside human beings like you and me are mutants, people who are half man, half wolf! But human and wolfman aren't exactly living in comity--one of the leitmotifs of The Sword of Morning Star is how terrible the wolfpeople smell to purestrain humies, and the contempt most humans have for the wolfmen, and the inferiority complex felt by the wolfpeople, who can't stand to look a real human in the eye!

The most civilized and sophisticated polities of this future world lie to the South in what are called "the Lands of Light," this is Italy, its capital Neoroma. To the North and East are "the Dark Lands," where live dangerous barbarians; I guess these are Scandinavia and Eastern Europe. Lying between the peaceful people of Italy and the barbarians is the "Empire of the Gray Lands" of what I assume is Germany, including the Kingdom of Boorn, whose king is Emperor of the Gray Lands; the duty of the Emperor is to protect the South from all those barbarians. (The novel's setting presumably reflects the fact that North Carolina-born Haas lived in Austria for some years.) Our hero, Helmut, is the 12-year-old bastard son of the King of Boorn; Helmut spent his youth in the palace, living the life of a prince, learning how to read, ride horses and sword fight and all that. The Emperor recently died of a mysterious illness, and the Emperor's legitimate son Gustav is the current holder of the throne, but he's a kid himself and rules under the close supervision of Albrecht, Duke of Wolfsheim. Albrecht is one of the few humans who like the wolfmen, and his ducal army is constituted of these smelly brutes--these lupine creeps can talk and walk bipedally and ride horses and fight with swords, just like a purestrain human, but their claws and fangs make them unbeatable in unarmed combat, a fact we see demonstrated in Chapter I when Albrecht lays a trap for Helmut's personal guard. The wolfmen kill Helmut's retinue, and Albrecht wants to kill Helmut as well, but Gustav insists his half-brother be spared. Helmut is sent into exile in the swamps, but only after Albrecht has chopped off Helmut's right hand so he can't wield a sword--a precaution meant to short circuit any attempts on an older Helmut's part to seek revenge or the throne for which he has a claim, should anything happen to half-brother Gustav.

In the swamps an ailing Helmut is revived and educated by a mentor character, Sandivar, a sorcerer who lives in an old 150-foot tall tower and can talk to the animals. This dude can put a saddle on a bear and ride around on it, which comes in handy when a ten-foot tall mud man, a mrogg, attacks in Chapter III.

Sandivar's powers enable him to view events over long distance of both space and time; in fact, his magical abilities seem practically unlimited, but whenever his powers threaten to undermine the plot, Haas has him claim that he can't do such and such a thing (like annihilate Albrecht's army with lightning bolts) because that would go against a vow he took to limit the use of his powers; it was overindulgence in special powers that led to the Worldfire, after all. (Following similar logic, Sandivar advises Helmut to refrain from building catapults, arguing that constructing such engines will set off an arms race that will lead to catastrophic results. This presumably reflects Haas's concerns about nuclear war, and perhaps a romanticism about war before industrialism, when, at least as Haas envisages it, combat was a test of bravery and muscle power conducted at close range.)

Anyway, thanks to abilities Sandivar does not hesitate to employ, he knows that the evil Albrecht has murdered Gustav and made himself Emperor, and that as Emperor he is going to make common cause with the barbarians of the North and pillage the practically defenseless South. This will be an even bigger disaster than it initially sounds like because the peaceful people of the Lands of Light are developing a vaguely defined "New Learning" that will bring peace to all the world. Sandivar can also see Helmut's future, and knows Helmut is the man who can stop Albrecht. Of course, Helmut is only twelve years old, but Sandivar has a plan for that! After getting Helmut all charged up to seek revenge by telling him that his father the Emperor didn't just get sick but was actually poisoned by Albrecht, Sandivar uses his sorcery to send Helmut to hell!

Haas proposes a universe of multiple dimensions that operate at different speeds. One such dimension is a world of war, where the shades of the great fighting men of history fight eternally; Beowulf, Siegfried, Arthur and Charlemagne are name-checked--interestingly, they are all Northern medieval heroes, and Haas directly names not a single one of the famous Mediterranean heroes of ancient times like Achilles, Hercules, Alexander or Caesar. Helmut stands in a pentagram and Sandivar intones a spell and the twelve-year old prince vanishes. Ten minutes later Helmut returns, but for each minute Sandivar waited an entire year passed in the dark and dreary dimension of war, and Helmut is now a twenty-two year old muscleman and a master of the battlefield! His trials in hell (which Haas only ever hints at--like Sandivar, we readers only see little Helmut vanish and then return as a grizzled veteran) have turned Helmut's soul to stone--he can no longer laugh or love, never again will the sight of the blue sky or the scent of the sea air bring him joy: "There was no love of life left within him." All he cares about is overthrowing Albrecht.

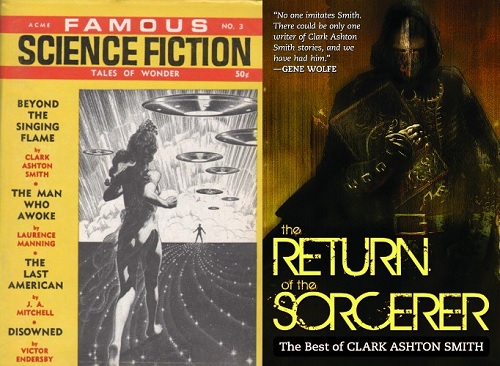

Sandivar takes Helmut on a trip to sunny Neoroma to get a powerful warhorse (a tremendous beast that, reminding us of the story of Alexander and Bucephalus, only Helmut can tame), a pair of huge hunting dogs, and weapons and armor made from a special super-strong metal. Halfway through the 144-page novel we get the scene we have all been waiting for after seeing Jeff Jones's cover for The Sword of Morning Star: the scene in which a blacksmith affixes to the stump at the end of Helmut's right arm the head of what Haas variously calls a mace or morning star. "Morning Star" soon becomes the name by which people far and wide call Helmut.

The second half of the novel deals with Helmut and Sandivar's campaign to overthrow Albrecht and put Helmut, the rightful heir now that Gustav is pushing up daisies, on the throne of the Kingdom of Boorn. Albrecht has disbanded the Empire's army of humans and replaced it with an army of wolfmen. The fortified town of the one noble who has been actively resisting Albrecht, Hagen of Markau, is under siege by an army of wolves (the quadruped kind) led by a sexy sorceress, Kierena ("dark of hair and ivory white of skin and red, red, red of lip"), who can transform herself into a huge black shewolf. Her enemies call her "The Black Bitch," but Albrecht has a crush on her and hopes to make her his Empress. As there is no human army at Helmut's disposal, Sandivar, saying that "fire must be fought with fire," recruits an army of bears and wild boars to lift the siege of Markau.

Sandivar's raising an army of bears and boars, while kind of cool, illustrates some of my gripes with the novel. First, there is the fact that Sandivar's capabilities wax and wane to suit the needs of the plot. Second, it is one of many examples of Sandivar, not Helmut, making decisions and solving problems. Helmut doesn't come off as an ambitious hero who makes decisions and bends his environment to his will, but as a guy who is led by the nose by a clever wizard to fulfill a prophecy. The Sword of Morning Star isn't about an individual's ability to overcome obstacles and achieve his vision, but about respecting limits and fulfilling the role handed you by others or by impersonal forces. Obviously the reader can see this is a strength, say that the novel is about one's duty to the community and the need to accept fate, but I kind of think following a bold individual who carves his own path might be more fun.

Anyway, the siege of Markau is broken and the wolf army wiped out. Kierena, whom I had hoped to see develop into an interesting character, is stabbed to death by Sandivar as she embraces him in hopes of seducing him--she knows she is not a powerful enough witch to match his wizardry and tries to undo him with her feminine wiles in a brief, cursory, scene. The bears and boars depart and Helmut rests in Hagen's castle, tended to by Hagen's beautiful blond daughter, Nissilda.

A recurring theme of the novel is men rejecting women's sexual advances. Back in Neoroma, Helmut, after having that mace head attached to his arm and fighting off five of Neoroma's muggers (I guess "the New Learning" has a ways to go), quickly became a celebrity, and the most beautiful woman in town, Lady Viira, came to his room intent on having sex with him, but Helmut, dead inside after his ten years in the bleak dimension of constant war, was indifferent to her charms, and in fury she slapped his face. Then Kierena, recognizing Sandivar, her former teacher in sorcery, as her wizardly superior, sought to seduce Sandivar rather than fight him, without success. And now, while Helmut and Hagen try to rebuild the Gray Empire army to use against Albrecht's army of wolfmen, we get Nissilda trying to win Helmut's heart. When Helmut tells her he is dead inside, she tells him that, to a woman, such talk is not discouraging, but is in fact an irresistible challenge:

"No man's so dead but what the right woman can bring him back to life. For that is what women are, my prince--life. It comes from us, and we tend it till it's grown, hold, suckle, nourish it. Women are specialists in life, as men are in killing one another off. And this I will say to you: show me a man convinced he cannot love, and every woman in the country will attempt to prove he's wrong. Your condition, to a woman, is not a disability, only a challenge."

"A challenge?"

"The greatest man can present to woman; and no woman could e'er turn it down."

|

| You have to love how they integrated the morning star idea into the back cover design |

As so often happens here at MPorcius Fiction Log, after airing a list of grievances against a piece of fiction I am going to tell you that it is fundamentally sound and I enjoyed it despite its various shortcomings; The Sword of Morning Star is alright. One frustrating thing about it is that Haas presents numerous intriguing ideas that he doesn't develop, like Helmut's relationship with Gustav (they grew up as brothers, but there was tension because strong warlike bastard son Helmut was Dad's favorite but fat Gustav, as the legitimate son, was destined to take the throne) and Sandivar's relationship with the dark beauty Kierena (Kierena seduced Sandivar before Helmut was born and convinced him to teach her his magic powers, which she used for evil); similarly we only get hints of what hell was like and what "the New Learning" down in Italy is all about. Still, the novel is competently constructed and written, and I'm judging this one acceptable/marginally good.

In our next episode, the sequel to The Sword of Morning Star, 1970's Exile's Quest!