|

| The cover of the British hardcover edition of The Other Side of the Moon (left) illustrates Clark Ashton Smith's "The City of Singing Flame" |

"The World of Wulkins" by Frank Belknap Long (1948)

It is the future! Ralph Denham is an antiquarian who has his study decked out to look like he's living in the nineteenth century and spends his free time at antique shops. He has a flirty wife, Molly, and two precocious kids, seven-year-old Betty Anne and eight-year-old Johnny. This guy is living the good life! But the universe is full of cosmic terror, and Ralph and his happy family are not immune!

Betty Anne insists they buy an ugly child-sized antique robot (a "goggle-eyed horror"), a wreck covered in rust, that they see at an antiques store. The droid is inert, but she wants play with it as if it were a doll, and christens it "Wulkins." The family takes a ride on a roller coaster, and the rattling and shaking of the machine brings Wulkins back to life! Immediately, Ralph notices bizarre visual effects all around him and surmises that Wulkins is no Earthly robot, but a scout from another dimension, sent to our world to seize samples and bring them back to its home plane of existence. Ralph grabs the little spy, pulls out some of its wires, and it is again deactivated.

Instead of simply destroying the alien invader, Ralph puts it in the basement, planning to show it to his scientific buddies. Betty Anne and Johnny, not realizing the danger their new friend poses, sneak down into the basement and repair Wulkins! Wulkins snatches up the kids and transports the entire house into another dimension; Molly realizes something is amiss when she looks out the window and the moon and stars and landscape look different than usual.

The Second Amendment must be alive and well in the future because when Betty Anne and Johnny's parents realize that their kids are in peril, Ralph grabs the energy pistol he keeps in his drawer and hoses down Wulkins, who has grown to ogre-size, with radioactive rays, damaging and driving off the alien robot. In a nearby building Ralph discovers a half-decayed insect creature lying on a slab; he presumes this alien built Wulkins and sent him out exploring the multiverse. Ralph also pockets some rolls of film he finds. Wulkins reappears, and after some more shooting, Wulkins dramatically commits suicide, and the Denham house and family somehow return to Earth. By examining the film Ralph figures out that Wulkins was not a robot; in fact, the bug was a robot built by Wulkins, whose body wasn't really mechanical but just looked mechanical to Earth eyes. One thing Ralph doesn't figure out is that it was his own kids, those scamps, who reactivated Wulkins and put all their lives in terrible jeopardy.

The premise and plot of "World of Wulkins" are not bad, and, in theory, a person who is actually good at writing could expend a little effort and shape such material into an effective horror and/or action-adventure tale. Unfortunately, Long doesn't develop the story carefully. The twist reveal--that the thing that looks like a robot is a scientist and the thing that looks like a bug is a robot--is poorly set up and pointless besides. (The obvious way to end the story is to reveal that the bug scientist put his soul into the robot body, and then while he was trapped on Earth his body decayed, and he committed suicide because he didn't want to live through eternity in a robot body.) One also wonders how Wulkins's suicide sent the Denhams back to Earth. Even worse, Long's poor writing style prevents the story from being told efficiently and mucks up the tone of the piece. Sentences and passages that should be concise and powerful, so that horror scenes convey terror or dread and fight scenes and chase scenes convey excitement and speed, are instead verbose and full of silly details that distract or confuse the reader. Long also tries too hard to be cute when describing the kids, which of course undermines all the horror and adventure elements.

Here are some examples of Long sentences that take the reader right out of the story and should have been taken right out of the story by the author or editor during revision or editing:

[Ralph rushes to dress quickly when he realizes the kids are in danger and he had to run outside:] Few men could have drawn on their shoes in exactly eight seconds. But Denham did it.

[Johnny, who has no idea what he is doing, starts working on the inert Wulkins in the basement:] There is a right way of tackling every problem and there is a wrong way. But there is also a way which is neither right nor wrong, but just--a way.

[Betty Anne has escaped into Molly's arms but Johnny is still in danger:] It was not only terror that she felt, but shame, that she could have forgotten even for an instant that she had a son. She hadn't really forgotten, not deep in her mind, but her relief at finding Betty Anne in her arms had spilled over into the warm, bright little compartment reserved for her son. Now that compartment was as cold as ice.In an October 11, 1926 letter to August Derleth*, H. P. Lovecraft says of Long that "Fiction is to him only a means of corralling cash--he is a poet and aesthete, & has put his real soul into the thin volume of verse he issued (at a doting aunt's expense) last winter." I can certainly believe that Long did not put his "real soul" into "The World of Wulkins," but just threw it together for money and sent it off to Thrilling Wonder Stories, where it first appeared. I'm afraid I have to give this one a negative vote.

After being reprinted in The Other Side of the Moon, "The World of Wulkins" lay dormant until it was revivified for inclusion in the 1972 Long collection The Rim of the Unknown, versions of which appeared in Great Britain in 1978 and in Italy in 1995.

*My source is the excerpts from this letter printed in the 2000 volume Arkham's Masters of Horror edited by Peter Ruber.

"The City of Singing Flame" and "Beyond the Singing Flame" by Clark Ashton Smith (1931)

The Other Side of the Moon includes a long story by Clark Ashton Smith, "The City of the Singing Flame," and I initially planned to read it, but isfdb suggests the version here in Derleth's anthology, a joining of two 1931 stories, was rewritten by a Walter Gillings, so I decided to check out the original versions from Wonder Stories, readily available at the internet archive.

"The City of Singing Flame" is introduced by a beautiful illustration by Frank R. Paul of a city of skyscrapers of diverse architectural styles inhabited by a throng of equally diverse alien beings. There is a brief prologue, and then comes the main text, the journal of Giles Angarth, who has disappeared along with his friend Felix Ebbonly. (There is a slight "meta" element to the story: Angarth and the man to whom the journal is addressed, Philip Hastane, are writers of fantasy stories, and Ebbonly an illustrator of such tales. Maybe these characters are jocular portraits of Derleth, Lovecraft, and Smith himself?) Angarth relates how, hiking alone at Crater Ridge, within sight of the Nevada Mountains, he stumbled on a hidden gateway and was mysteriously transported to a world of purple and yellow forests, just outside a city of red spires.

This story feels long and slow, with lots of description and little plot. There is none of the sex and violence, little of the humor or terror that has made so many other Clark Ashton Smith stories so effective. Another disappointment is the style: many Smith stories are written in a sort of poetic or fairy tale style which is good at generating a fun or creepy "I'm in an alien world" mood, but, I guess because this story is written in the voices of early 20th-century people, the style of "The City of Singing Flame" is sort of flat and boring.

One thing that makes the story feel slow is that Angarth keeps taking the gateway back and forth between Earth and the alien world over a course of some days, on each trip advancing a little further, getting scared, and scurrying back to Earth to write in this journal.

Anyway, Angarth discovers that the red city is a place of pilgrimage, where aliens come from all over the universe to see a huge flame in a vast shrine. Many of the pilgrims jump into the flame to be incinerated. A musical vibration with hypnotic effect apparently entices people into this flame; like the many different aliens, Angarth is strongly attracted to the flame, but he puts cotton in his ears and resists the urge to immolate himself. On his last trip he brings along his friend, Ebbonly. Ebbonly decides to forgo use of the cotton and he runs into the flame and is annihilated. In his last journal entry, Angarth tells us that he is going to throw himself into the flame tomorrow--the influence of the musical vibration has apparently convinced him that dying in the flame will be "splendid" and "glorious" in comparison to his "monotonous" and meaningless day-to-day life.

I like the themes and ideas of this story, but it is just too long and Smith doesn't bother to set up the characters of Ebbonly and Angarth ahead of time as people who are depressed or bored with the monotony of life. If Angarth and Ebbonly had been frustrated in their careers or love affairs or hated society or something, their suicides would make more sense and would represent a culmination and/or catharsis; as it is, Hastane in his prologue says they are successful in their careers; we readers have to assume they only commit suicide because of the vibration's powers, which is less interesting than if their actions were a result of their own psychologies.

I'd have to say this one is merely acceptable, but maybe it is not fair to judge "City of Singing Flame" on its own, and I should reserve final judgement until I have read "Beyond the Singing Flame." (Though SF fans in 1931 would have judged "City of Singing Flame" on its own, as it appeared in the July issue of Wonder Stories, with the words "THE END" on its final page, and the sequel would not appear until the November issue, four issues later.)

"Beyond the Singing Flame" is as boring and plot-lite as its predecessor, and more nonsensical, and throws away all the suicide stuff that made "The City of Singing Flame" sort of interesting. This entire story is narrated by Philip Hastane, who goes to Crater Ridge to find the gateway. He is transported to the red city, as were Angarth and Ebbonly, but finds it under attack by another city, a city of towers that walk on mechanical legs and project bolts of energy at the city of the Flame. Hastane is carried aloft by two friendly aliens, butterfly-people on a pilgrimage to the Flame, who fly him right into the Flame!

To Hastane's relief and my dismay the Flame doesn't burn you up, it "revibrates" your atoms so you are sent to a higher plane of existence, one of "immense joy," "liberation" and "ecstasy." Here one has new senses and abilities that enable one to experience new forms of beauty and happiness. Angarth and Ebbonly have been waiting for their friend Hastane, and welcome him to this Eden. This paradise, however, begins to shiver and shake--it is sustained by the Flame, and the Flame is under attack back in the red city! The three Earthlings fly (that is one of their new abilities) towards another gateway that will take them to another paradise, but they don't make it; when the Flame expires the paradise expires, and the three men reappear in the ruins of the red city, next to where the Flame once burned. Poor Ebbonly is crushed to death by a falling column, but Angarth and Hastane live on, haunted by the memories of their time in heaven. Luckily, the evil city that demolished the red city left intact the gateway that leads back to Earth.

I have to give this exercise in tedium a thumbs down.

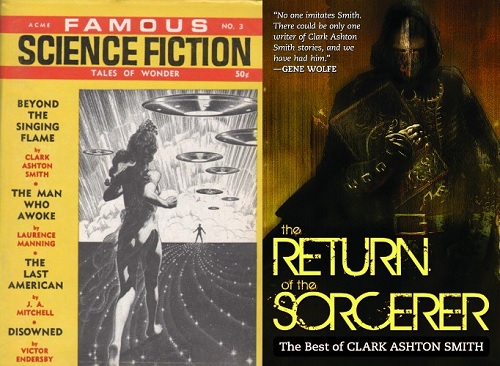

MPorcius Fiction Log may have lowered the boom on "The City of Singing Flame" and "Beyond the Singing Flame," but many SF fans over the decades have sung the praises of these tales. Editor Mort Weisinger reprinted "The City of Singing Flame" in the same 1941 issue of Startling Stories that saw the debut of Edmond Hamilton's A Yank in Valhalla, and alongside it is an essay by Harry Warner, Jr. explaining that "The City of Singing Flame" is his favorite, "one of the finest fantasies ever written." Robert A. Lowndes reprinted the stories in his 1960s magazine Famous Science Fiction, and they were also included by editor Robert Weinberg in 2009's The Return of the Sorcerer: The Best of Clark Ashton Smith. What can I say? Here at MPorcius Fiction Log we are iconoclasts!

"Beyond the Wall of Sleep" by H. P. Lovecraft (1919)

The narrator of "Beyond the Wall of Sleep" is a medical professional with some unconventional ideas about sleep and dreams. "From my experience I cannot doubt but that man, when lost to terrestrial consciousness, is indeed sojourning in another and uncorporeal life of far different nature from the life we know....Sometimes I believe that this less material life is our truer life, and that our vain presence on the terraqueous globe is itself the secondary or merely virtual phenomenon." So he is pretty stoked when an inbred and illiterate hillbilly from the Catskills, Joe Slater, who is said to have really crazy dreams, is dragged into the insane asylum where the narrator is working as an "interne."

All his life Slater has disturbed and amazed his fellow hill people (whom the narrator variously describes as "white trash," "primitive," "barbaric," "repellent," "decadent" and "degenerate") with the vivid stories of his dreams, which he himself forgets within an hour of waking. The police nabbed him after he, in a fit of madness during which he yelled about his need to achieve revenge on an alien "thing," beat a fellow hillbilly to a pulp. Acquitted by reason of insanity, Slater has been consigned for life to the state mental hospital, where the narrator conducts unauthorized experiments on him.

These experiments consist of the narrator attaching to Slater's head a sort of transmitter and to his own head a receiver, which he hopes will allow him to experience Slater's thoughts. It is on the night that Slater dies, his health having precipitously deteriorated in captivity, that the narrator finally gains the insights he seeks, and learns the astonishing truth, that cosmic entities that are chained to our bodies by day explore the universe at night, interacting with alien life forms and waging war against malevolent oppressors.

Technically, "Beyond the Wall of Sleep" is vulnerable to the kind of complaints I leveled against Smith's "Singing Flame" stories: it is mostly description and has little plot and is kind of nonsensical. But Lovecraft's story is far superior. First, it is short, and does not get tedious. Second, Lovecraft fills the story with uneasiness and tension by including the horrible killing, the constant reminders of how primitive and disgusting the hillbillies are, the obsessive quest for vengeance of the cosmic entity bound to Slater's body, and the fact that the narrator's theories and experiments are not approved by his superiors. I like this one.

"Beyond the Wall of Sleep" first appeared in an amateur periodical called Pine Cones, and in 1934 was reprinted in the fanzine The Fantasy Fan; in 1938 it was printed in Weird Tales. In 1943 it was the title story of the Lovecraft collection Beyond the Wall of Sleep, which features Clark Ashton Smith sculptures on its cover, and since then has been reprinted in many anthologies and collections. I read it in my Corrected Ninth Printing of Dagon and Other Macabre Tales (2001.)

"Something From Above" by Donald Wandrei (1930)

In July of 2017 I read three stories by Donald Wandrei; two of them, "Raiders of the Universes" and "The Fire Vampires," start with astronomers spotting some odd phenomena in the heavens. "Something From Above" starts similarly, with a detached journalistic account of some astronomers noticing lights in the sky and the occlusions of some stars. The second part of the story details the horrible adventure suffered by a Norwegian-American farmer, Lars Loberg, and his wife Helga, in western Minnesota. (Wandrei attributes some of Loberg's character traits to his ethnicity in a way we perhaps would not today.) To make a long story short, Lars and Helga encounter a number of strange phenomena, like red dust falling from the sky, the discovery of a huge gouge in their field that is occupied by a large invisible object, and then, horrifyingly, Helga's disappearance while Lars isn't looking--she later falls from the sky, frozen and dead. Lars goes insane and burns Helga on a funeral pyre, and then sets fire to the large invisible object, which we readers of course recognize as an alien space craft. The space ship explodes, killing Lars.

In the third part of the story the mysteries of the first two parts are explained. Solo pilot Larry Greene was flying over Minnesota when aliens from Saturn sucked his plane up into space with a tractor beam to ask him to be Saturn's liaison with Earth. (Poor Helga got sucked up by mistake.) The Saturnians, people made of gas, are defending our solar system from some hostile extrasolar aliens--the dust and invisible wreck that landed on the Loberg farm were what was left of an invading ship shot down by the Saturn flyboys. While he visits their ship, the Saturn people explain a lot of sciency stuff and Saturn history to Greene; then they send him back down to Earth. Unfortunately, Greene's time in space has frozen parts of his body and he dies of these injuries--fortunately he lives long enough to write about his adventure.

"Something From Above" isn't bad. Maybe the prevalence of collateral damage is sort of unusual? The story first saw print in Weird Tales, and besides in Wandrei collections and here in The Other Side of the Moon, it would be republished in Donald Wollheim's Avon Fantasy Reader, in the same issue as reprints of Robert Bloch and Henry Kuttner's "The Black Kiss" and Frank Belknap Long's "The Hounds of Tindalos."

**********

It is always fun to dig into what the Weird Tales gang was up to in their heyday, but for our next few blog posts we'll advance forward a few decades and check out some sword-swinging paperbacks from the late '60s and 'early '70s.

No comments:

Post a Comment