"Warm Man"

"World of a Thousand Colors"

"En Route to Earth"

"Solitary"

"Eve and the Twenty-Three Adams"

"Journey's End"

"Prime Commandment"

"The Four"

"Dark Companion"

"Halfway House"

"World of a Thousand Colors"

"En Route to Earth"

"Solitary"

"Eve and the Twenty-Three Adams"

"Journey's End"

"Prime Commandment"

"The Four"

"Dark Companion"

"Halfway House"

Remember when I told you that "Dark Companion" and "Halfway House" had good settings and good characters but were a bit lacking in the story department? Well, the same description might apply to "By the Seawall," but this story is more entertaining and more satisfying.

The ocean is teeming with huge ravenous monsters of every type--fish, reptile, crustacean, you name it. These creatures like nothing more than to come ashore and eat people by the dozen. (This is some far future Earth, I guess.) So, a century ago, a towering sea wall was built to keep the monsters away. Our protagonist is an android, a being more or less genetically similar to a man, but grown in a vat and designed to be more resistant to boredom as well as stronger and faster than the general run of all-natural sex-produced humans like you and me. Such synthetic men have the job of patrolling the seawall, monitoring the condition of the wall and keeping an eye out for any monsters who might somehow figure out how to overcome the wall and its attendant electric and toxic defense mechanisms.

Our hero is doing this job as usual when he witnesses a human commit suicide by diving off the seawall (his fall eased by an anti-grav device) and swimming out to be devoured by one of the giant sea monsters. This turns out to be the first in an epidemic of such suicides that grips the human race, and the androids are hard pressed to deal with it. Nobody can really figure out why the suicides are taking place--maybe the human race can't bear to be separated from its ancestral home, the source of all life? When the protagonist arrests a woman who is trying to kill herself, he asks her about her motivations, and she says she wants to "belong" to the sea and insists that, as a "machine," he could not understand. Soon after, the android, perhaps shaken by his failure to prevent suicides, perhaps seeking knowledge of what it is like to be truly human, dives into the ocean himself to be eaten.

"By the Seawall" is better than "Dark Companion" and "Halfway House" because of the striking images Silverberg conjures up of the wall and the monsters, and because the ending is more conclusive, more satisfying, even though we don't find out why the humans--and now androids!--are feeding themselves to monsters, and the problem presented to the main character is not solved. The issues the story addresses--the mystery of human psychology and sociology and the question of what kind of relationship natural and artificial humans might have--are compelling.

Thumbs up for "By the Seawall." After its debut in If, the story would reappear in several European publications as well as Dimension 13.

This is a wacky story, I guess partly intended to shock the reader and partly intended to make him laugh with its matter-of-fact first-person account of a society whose social mores are radically divergent from the mid-20th-century conventional. These kinds of stories lack human drama and feeling, and I am not crazy about them, but "Bride Ninety-One" is competently told, so I'm calling it acceptable.

It is the future, and a civilization made up of many different intelligent space-faring species stretches across the galaxy. For these people, sex and marriage has been totally divorced from reproduction, and marriages last only six months, and it is normal for people to marry dozens of times, and to marry outside their species.

The narrator, a human, has just started his 91st marriage, to a slender being with petals, flexible limbs and an "ingestion slot" equipped with needle-like teeth. The story recounts their six-month marriage, which faces various crises because the needle-toothed alien wants to have a traditional Terran marriage, but her ideas of what constitutes a traditional Terran marriage is flawed, being based on historical novels she has read. For example, she thinks human males always cheat on their wives, so when the narrator passes up an opportunity to bang some other woman, needle-teeth is broken-hearted. Similarly, needle-teeth saves the day by pacifying a rogue beast at a rodeo after all the men have fled in terror from the berserk monster and has to be told that in a Terran relationship it is the man's job to protect the woman, not vice versa. (The prelude to this scene is depicted on the cover of the issue of If in which "Bride Ninety-One" debuted, but Gray Morrow didn't try to depict the bride, suggesting a lamentable lack of ambition or perhaps a failure to actually read the story--maybe Fred Pohl or Judy-Lynn Benjamin just told Morrow over the phone to "draw some cowboys with an alien bucking bronco.")

(Maybe I need to point out that the narrator insists he loves the little lady and that the two of them have sex often, the narrator does not hesitate to kiss his wife's needle-filled "ingestion slot.")

Marrying the same person twice is taboo, but, at the end of the story, needle-teeth wants to marry the narrator again. He agrees when she explains that the marriage will be totally different, as this marriage will follow the customs of her race. The narrator has his human teeth removed and needle teeth implanted, and learns that he will be married not only to this individual, but all her many sisters.

This studied bit of bizarrerie debuted in If and seems to have been a hit among European editors--"Bride Ninety-One" has been translated into five languages, according to isfdb. Karel Thole took a stab at depicting the bride on the cover of the issue of Urania in which the story appeared--as I have remarked before, Thole's work indicates he actually read the stories he illustrated.

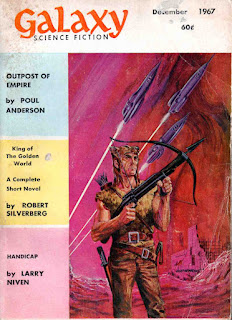

"The King of the Golden River" made its first appearance as "The King of the Golden World" in Galaxy. We've already read a story from this issue of Galaxy, Fritz Leiber's "The Black Corridor," and one presumes the day will come when we read the Poul Anderson and Larry Niven stories from the issue, "Outpost of Empire" and "Handicap." As "The King of the Golden River" the story would resurface in various Silverberg collections, and in 1969 translations appeared in the French edition of Galaxy as well as issue of Urania devoted to Silverberg and Kit Reed.

Here we have another story about a human who has sexual relations with an alien. Elena, a Terran, is on an alien planet, living among nudist monkey-people on a volcanic island. She is sleeping with the chief (if you are going to bang aliens, might as well shoot for the top, right?) and the very first scene of the story involves Elena, naked of course (when in Rome...), hanging around with a crowd of native kids, observing the smoking and burbling of an active volcanic crater, and how one of the kids, nine years old, keeps touching her thigh with his six-fingered hand--Elena wonders if he just being friendly, or if this constitutes erotic groping.

Silverberg must have read a book about volcanoes, because he spends a significant amount of time describing the different ejecta that come out of the crater as the eruption approaches, smoke, ash, pumice, cinders, lightning bolts, etc. Elena keeps asking the chief why everyone isn't evacuating, as it looks like when it comes the river of lava will run right through his villages, totally destroying them. Eventually the big cheese gives her an answer, and we have our twist ending--every five generations the volcano erupts, and the villagers eagerly embrace the event, all but a select few of them welcoming death. The chief and the priesthood have selected who will survive, and the elect depart to a safe distance--the chief and the clergy are not among them. As an alien, Elena will be permitted to flee, but Elena decides to put her money where her mouth is, so to speak--she has been trying to join this community of hairless monkey-people, to become one of them, and getting killed with her husband is a way for her to prove to herself that she is sincere. (As in "By the Seawall" and "Journey's End" the protagonist gets killed in the course of exploring or asserting his or her identity.)

I am guessing "The King of the Golden World" is not only Silverberg's opportunity to teach us about the behavior of volcanoes, but to express his own (or appeal to readers') fears of overpopulation and attachment to the theory of the noble savage. RE: Overpopulation, we are told that on Earth births are highly regulated and children are scarce and that Elena was initially disturbed by the hordes of children among the natives. RE: Noble savage, Silverberg certainly paints the monkey-people in the best possible light--they are graceful and the chief is "unhurried" and "confident, a true king" who is "hailed by all." Maybe Silverberg thinks we'd all be happier if we wore no clothes, were less sexually repressed, had admirable leaders we obeyed, and were so committed to the environment that we committed mass suicide every century or so.

It is dimly possible that this story is a subtle dig at hippies and the like who rebel against Western middle-class society and romanticize the ways of primitive foreigners without recognizing the unhealthy or dangerous aspects if those non-Western societies, but "The King of the Golden World" seems very earnest and I doubt it.

Either way, I'm judging "The King of the Golden World" acceptable.

Alright, another of our projects is behind us. Taken as a whole, the thirteen stories in Dimension Thirteen are not bad, though there are some clunkers in there, and the acceptable and good stories share a similar tone and structure. We get an interesting setting and some science material about future medical developments or volcanoes or teleporters or how to build a giant wall to keep out monsters, and then what feels like an abbreviated plot with a downbeat ending in which the protagonist fails to overcome the plot obstacle, or does so at tremendous cost--people tend to die at the end of these stories, and a lot of them feature suicide. Like half of the stories prominently feature sex between humans and nonhumans, or some other form of odd and potentially repulsive sex. The stories in this collection are not meant to cheer but to disturb or shock the reader.

There will be more Silverberg in our future, but first we'll explore some 1950s short stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment