We here at MPorcius Fiction Log are reading stories from 1958 that famous SF writer and anthologist Judith Merril recommended in the back pages of the fourth of her acclaimed SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy anthologies. Merril's list is organized alphabetically by author, and we are cherry picking stories that pique our interest, starting from the "A"s and making our way to the "W"s and the "Y" (Robert F. Young.) Today we finish the "B"s and start on the "C"s with three pretty big names in the speculative fiction world.

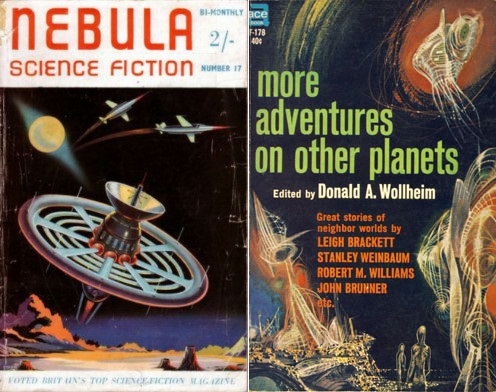

"Substitute God" by John Brunner (1956)According to isfdb, John Brunner's "Substitute God," printed in a 1958 issue of Fantastic Universe, is a version of the story "By the Name of Man," that was published two years earlier in a 1956 issue of Nebula. Somewhat amusingly, Merril actually recommended "By the Name of Man" in her list of 1956 stories in the second edition of her yearly Greatest anthology. Whether this is a mistake (I certainly don't recall the plots of every story I read two years ago) or intentional, Merril thinking this story is so awesome that she embraced an opportunity to spread the good news about it a second time, I don't know.

I don't actually read Brunner much. What work of his I read before starting this blog didn't impress me much, the stuff people say about his big famous novel, Stand on Zanzibar, makes it sound like a book that would annoy me, and when I read a 1960 story of Brunner's a year ago I found it to be a total waste of time. But today, in a spirit of exploration and reconciliation, I'm going to read "Substitute God" in Fantastic Universe. I actually own a copy of this magazine, and have blogged about three of the stories in it, those by Harry Harrison, L. Sprague de Camp and Edmund Cooper.

"Substitute God" is one of those SF stories that reminds me of Somerset Maugham tales that describe British guys spending long years far from England and other white people, administering native villages, and how differently different Britons respond to exposure to and responsibility over the locals. Lattimer is on Venus, managing a village of the primitive natives. The villagers consider him a god, practically infallible, and Lattimer lives under the stress of trying to appear perfect before them; he has made progress in this village, among other things guiding the natives in the building of levees and use of crop rotation to enhance the efficiency of their agriculture, and if they realize that he is fallible, that he is not absolutely wise and divinely just, not a god but just another person, all his achievements will be jeopardized and his own life, and even the position of all Earthmen on Venus, will be put at risk.

Another human appears within Lattimer's territory. This guy, Tomson, must be a fugitive, a criminal, fled to the swamps of Venus to hide from the Terran government. The Venusians think all humans are gods, and if the natives see this guy committing blunders or acting immorally they may realize that humans are no more divine than they, which will be a disaster. Sure enough, Tomson makes trouble but some good luck and some quick thinking on the part of Lattimer save the day.

"Substitute God" has a good twist ending. In this future, criminals are "psyched," which presumably means after conviction their brains are tampered with to make them more honest and law-abiding. Tomson is sent off to be psyched after the climax of the story, and in the denouement, some months later, he returns to Lattimer's village to take Lattimer's place as the villagers' god. Having been psyched, Tomson is now a responsible individual. On the last page of the story we learn that Lattimer himself is a murderer, that he killed a woman some years ago and was psyched and then sent to this village to manage it as the villagers' god.

This is a good story; the pacing and all that stuff is good, and Brunner does a good job of instilling in the reader the tension suffered by Lattimer as he tries to appear perfect in front of the natives and then finds another Earther has arrived to throw a monkey wrench into the carefully calibrated works. "Substitute God" also addresses the fascinating topic of the utility and ethics of religion and government--tricking savages into thinking you are a god, and messing around in a man's brain to radically change his personality, seem prima facie like immoral intrusions, but maybe in some circumstances these extreme measures are justified by the good that can be realized for those intruded upon as well as for third parties.

So it looks like I am giving Brunner an enthusiastic thumbs up here and may be revising my opinion of him. It is nice to have some good news.

In 1963 this story reappeared in Donald A. Wollheim's More Adventures on Other Planets under the "By the Name of Man" title.

Five or six centuries ago robotic probes discovered planet Thalassa, and three hundred years ago the world was colonized by Earth people who arrived in suspended animation after a trip of many decades. Thalassa is mostly covered in ocean, with only a single island upon which to build farms and homes, so no more colonization ships have ever come to the place, and Thalassa has been out of contact with Earth for all 300 of those years.

Clyde is a fisherman; his fiance Lena is the daughter of the Mayor of the Thalassan village where they live. Their simple lives are thrown for a loop when a colony ship, still over a hundred years from its destination, takes up an orbit around Thalassa and a space boat lands engineers and officers near Lena and Clyde's village to collect the supplies they need to repair the malfunctioning colony ship. Lena falls in love at first sight with one of the engineers, Leon, and they consummate their relationship after Lena is powerfully moved by the sound of Earth music that nobody on Thalassa has ever heard.

After a few weeks Leon and his comrades get all they need from the planet, and prepare to return to the colony ship and leave Thalassa. Lena is heartbroken and begs Leon to stay, and then to let her join him in the effort to colonize the far distant planet to which he is headed. Leon, as we expect of a sailor, isn't too hung up on Lena and to show her how impossible it would be for them to remain together he takes her up to the colony ship, a thing two miles long. Leon takes Lena to the vast chamber where the corpsicles of the two thousand colonists are stored, and shows Lena his pregnant wife. Clyde gets Lena back, but we have reason to believe she will always think of Leon as the love of her life.

The love triangle works, and all the speculative technology and society stuff Clarke comes up with (e.g., the colony ship propels a huge icebergs before its bow to absorb stray atoms and meteors that, when it is travelling at near-light velocities, could wreck it, and Leon and his colleagues have landed on Thalassa to use anti-grav technology to direct a huge volume of water up into space to their mother ship; and Earth people, Leon tells Lena, no longer live in cities because telecommunications technology has rendered living in close proximity pointless) is interesting. A solid classic-style science fiction story--thumbs up for "Songs of Distant Earth."

"Songs of Distant Earth" was included in the oft-reprinted Clarke collection The Other Side of the Sky, some of the American editions of which have a creepy cover by Fernando Fernandez, the creator of the awesome NSFW graphic novel Zora, which goes for over $100 on ebay but which you can read/ogle for free online if you look around a little.

|

| Left: Fernando Fernandez Right: Ralph Brillhart |

Three successful stories about human relationships in the space faring future; Merril guided us ably on this leg of our trip through 1958.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment