"Guns of Maiden Hill" (1934)

The publication page of The Eerie Mr. Murphy says that this story appeared "in a much different form" in the July 1934 Astounding under the title "Guns of Eternal Day." It was printed in F. Orlin Tremaine's magazine under the pen name Howard W. Graham, Ph.D, apparently because Howard's brother Donald also published stories in Astounding. If Wandrei didn't actually earn a doctorate this pseudonym is all the more amusing, and perhaps a sign that Tremaine or whoever felt that Astounding's slide rule-cradling readers really wanted their fiction to be produced by people with noggins full of book-learnin'--even if the stories didn't necessarily present eggheads and their knowledge as an unalloyed good!

"Guns of Maiden Hill" is a case in point. It is one of those SF disaster stories for which the author has come up with a wild science idea of how the Earth might get totally wrecked and the human race threatened with destruction, and then tries to construct some human drama to add to his speculative cataclysm in an effort to produce a full-fledged story and not just a list of horror scenes of buildings falling over on screaming crowds and oceans boiling fish alive or whatever. Marrying the human story to the science idea can be difficult, however, and I think Wandrei doesn't quite hit the mark this time around.

A doctor has been practicing in Philly for three years since the death of his father. Tonight, finally, Doc and his adult daughter drive up to the Minnesota farm he inherited from Dad, planning to move in now that Doc has retired. The moon looks very strange, very red, and when they get out of the car Doc and daughter feel that the moon is actually emitting heat!

They notice something else--someone has built some massive structures on the stony hill on their property! Doc and daughter drive over there, confront the men there, and are eventually directed to the boss of the project, a college professor of independent means. This brainiac explains that he has figured out how to turn the moon into a second sun by projecting rays from powerful ray guns (the structures on the hill) at Earth's beloved satellite for a few hours. These particle projector cannons requires a stable platform, and this farm was chosen because of the exceptionally stolid granite deposit that forms the hill. The college prof claims that he tried to figure out who owned the farm, so he could buy it, but was unable to and just went ahead and set up his huge apparatus on the hill anyway. He asserts that he now legally owns the property because of "squatter rights." (As if a go-it-alone college professor wasn't scary enough already, this guy also thinks he's a god damn lawyer!) This guy has deep pockets to match his big ego and bog brain, and hands the Doc a big check right there, in hopes this will placate the physician. An overly large portion of this story has to do with the psychological and legal ramifications of just taking over apparently abandoned property; not only is this stuff disconnected form the science idea that is the raison d'etre of Wandrei's story, but it doesn't make any sense, as Doc has continued to pay property taxes on the land, so the local government is well aware of who owns the farm and figuring out who would have been trivially easy.

As for the science idea, the scientist says he is turning the moon into a second sun because it will diminish crime and increase agricultural yields. He thinks he is presenting mankind with a terrific boon! But the last page of the story describes how wrong this college professor was. The increase in heat drives people bonkers. The polar ice caps start to melt. Changes in the environment lead to plagues, and the prof is one of the first to die from the new pathogens. Giant gila monsters and giant scorpions appear in the desert states and cause even more havoc than the lanternflies I keep seeing in Hagerstown. And so on.

Then comes the deus ex machina ending. By coincidence, a huge comet passes by the Earth three years after the moon has been transformed, and it carries the moon away, liberating us from its terrible light and heat.

Mediocre, and I am being generous with that assessment, perhaps--the legal property rights stuff is boring and has little bearing on the SF elements, and the comet business is even more out of left field and equally unnecessary--the story would be better if the college professor had killed us all.

"The Eerie Mr. Murphy" (1937)

Editor D. H. Olson tells us "The Eerie Mr. Murphy" represents the high point of Wandrei's career as it was printed in the prestigious and high-paying Esquire. (Most of the previously published stories in The Eerie Mr. Murphy saw print initially in the low class and poorly paying Spicy Mystery and Speed Mystery.) This is the only story we are reading today to have originally appeared in print under Wandrei's real name, and you can see his moniker right there on the cover, next to the cartoon about how a guy will waste his money on a fancy car in order to impress a blonde. "The Eerie Mr. Murphy" has been reprinted in a number of places, including August Derleth's The Night Side and John Pelan's The Century's Best Horror Fiction.

In the title story of this collection we have a gimmicky sort of thing, basically a series of gags. Murphy is an unattractive little guy who I guess you could call a jinx, though Wandrei doesn't use that word. Sporadically, tools and machines inexplicably fail around Murphy, and natural laws temporarily cease to operate; Murphy does not really cause or will these failures, and in fact wishes they wouldn't happen; Wandrei suggests this "power" is like a hungry monster inside of Murphy. Though he has little if any control over what failures will occur, Murphy is able to predict them, and feels guilt over them.

After his presence triggers an airplane crash that kills a bunch of people, Murphy gives himself up to the police, but they can't confine him. They experiment on him, shooting pistols at him--the bullets lose velocity after leaving the barrel and harmlessly fall to the floor--and nail him up in a crate--he disappears.

This is another underwhelming piece that consists of an idea and is lacking in plot and human feeling, and the idea is actually less compelling than the idea in "Guns of Maiden Hill." Barely acceptable.

When I was a kid, quicksand was a menace you would often see on the idiot box, but, in the same way that today everybody knows that "Every Breath You Take" is not a sweet love song but is in fact about a creepy stalker, the once-esoteric knowledge that quicksand is not real or is not dangerous is now widespread.

Fortunately, "Danger: Quicksand" is about more than the debunked danger that gives it its name; it is a decent monster story. It isn't as original as "The Eerie Mr. Murphy," I guess, but it has more tension and excitement and has a beginning, a middle and an end instead of just being a gimmick and a catalog of gags. (I don't actually read Stephen King, but from hearing people talk about Stephen King, I feel like "Danger: Quicksand" is the kind of story Stephen King writes.)

A new dam has just been completed, and a swamp in a depression is going to be flooded by tomorrow morning, creating an artificial lake. Four rich kids in their twenties, after midnight, after they have had a few drinks, decide to drive on the treacherously narrow and winding road that goes through the swamp one more time. (Remember Deliverance?) Their car gets stuck, and it turns out they have driven onto a huge monster, a big flat thing like a skate or ray that has orifices on its upper surface that can generate enough suction to hold the car fast and suck the flesh right off a wealthy young lady's bones! This monster is, apparently, the product of chemical reactions in the swamp's abandoned garbage dump that were activated by a lightning bolt. (Remember Donald Wollheim's "The Rag Thing?") Will the rich kids be eaten and their bones lost forever under the artificial lake, or will they escape with their lives?

The rich kids are portrayed in a less than sympathetic fashion, which helps to make you wonder if they are going to make it out of the swamp alive or not.

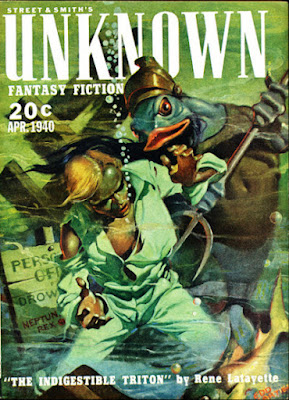

"Danger: Quicksand" first appeared in John W. Campbell, Jr.'s Unknown, but was not reprinted until the 21st century here in The Eerie Mr. Murphy.

"The African Trick" (1940)

Here's another piece from Unknown. Wandrei's "The African Trick" appears alongside stories by an entire roster of famous and important writers, from L. Ron Hubbard to Theodore Sturgeon, Henry Kuttner and Jack Williamson. I will have to read more from this magazine some day. (Every week I read X pages of material and discover 2X pages of material I want to read.)

"The African Trick" is far and away the best story we are reading today, and I strongly recommend it to fans of the weird and of horror stories in general. A really good story of sex, violence, exotic climes and black magic!

Vladimir Kirov lives in a fine Manhattan apartment and lives a fun lifestyle, going to nightclubs at all hours. How does he finance this lifestyle? By blackmailing his employer, Dr. Junius Leyden, world explorer and crack shot with a revolver! As the story begins, Kirov receives a strange package from the perennially out-of-town Leyden, postmarked Africa, containing a bizarre seed or bulb and detailed instructions in how to plant it. Kirov, you see, is an expert gardener. The seed, suspended in a jar full of special fluid, is a beautiful brunette white woman, comatose and six inches tall!

As the story progresses we learn how Leyden acquired this outré seed (from a lost tribe of blue-eyed white people in a remote village in an almost inaccessible region of Africa whom he befriended by saving their leader from a monster snake) and all about the Leyden-Kirov relationship, particularly the foul deed which Kirov witnessed, thereby securing for the Russian green thumb both Leyden's enduring financial support and eternal enmity. And we witness the occult purposes Leyden has for sending the seed to Kirov, and Kirov's reaction to returning from the clubs long after midnight to find a beautiful woman in his apartment clad in his clothes.

The structure, pacing, writing style and characters of this story are better than those of the other three we have read today, and I love the subject matter--I am of course crazy about mad scientists, black magic, exploring weird places, and disastrous sexual relationships. Wandrei does a great job describing everything and everybody, really bringing them to life.

An enthusiastic thumbs up for "The African Trick." It is odd that it was never reprinted until the publication of The Eerie Mr. Murphy--a reminder that gems can lie uncollected in the rich veins of the old pulps for decade upon decade!

**********

I am thrilled by Howard Wandrei's art and so I am very glad to own The Eerie Mr. Murphy, but I cannot deny that the fiction in the book has been a little disappointing. Happily, "The African Trick" goes some distance towards easing that disappointment. We'll be reading more Howard Wandrei in the future, and I am hoping we'll find more stories as good as "The African Trick" or at least "Danger: Quicksand."

No comments:

Post a Comment