(We read the first four stories in the book, in which feature plenty of scoundrels, mysterious deaths and strange artifacts, earlier this month.)

"The Sympathetic Souse" (1954)

After first appearing in Lilliput, "The Sympathetic Souse" has been in multiple collections, including Men Without Bones and The Best of Gerald Kersh.Dr. Almuna thinks the human mind is too complicated to really understand, rendering psychoanalysis bunk, and in conversation to the narrator likens Freud and the psychoanalysts to witch doctors, joking that Dracula, werewolves, and psychoanalysts all come form the same region of the world, the Carpathians.

At a party, a medical guy tells a story of sympathetic pains--a young woman in 1944 suddenly got a pain under her collar bone and cried out--it was later learned that at that very moment her brother had been shot on the battlefield under the collar bone. Then Dr. Almuna tells his story of "physical sympathy."

The brothers John and William came to see Almuna, John complaining that while William constantly drank booze and smoked, it was he, John, who never drank or smoked, who suffered the ill effects: a red nose, coughing fits, sickness in the stomach, etc. Kersh goes on in this vein for some pages, how William's vulgar and indulgent behavior inconveniences and discomforts the sober and abstemious John. Then at the end of the story comes the lame punchline which doesn't really make any sense--John and William were Siamese twins.

Besides the fact that the ending is an annoying trick, Almuna having conveniently forgotten to mention that John and William were conjoined twins, the three segments of the story barely go together--the first part is about how psychoanalysis is a scam, the second part has nothing to do with psychology but describes a psychic or supernatural phenomena, and the third describes a (quite dubious) purely physical phenomena.

Thumbs down.

"The Queen of Pig Island" (1949)

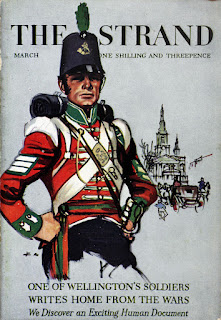

Here's another piece that was given the nod by Simon Raven for inclusion in The Best of Gerald Kersh. It first appeared in The Strand and later in Playboy under a different title ("Mistress of Porcosito") and in Nightshade and Damnations, the 1968 edition of which not only had an intro by Kersh superfan Harlan Ellison, but a cover by Ellison's favorite illustrators, the Dillons."The Queen of Pig Island" is the history of a circus freak, based in part on the memoir she wrote that was found in a bag near her skeleton on a small island; Lalouette, born with no arms or legs, died on that island after the ship her circus was sailing to Mexico upon sank.

Lalouette was a cultured genius, born to an aristocratic family, well-read, fluent in five languages, able to paint and write and clothe herself just with her mouth. When she was shipwrecked along with the circus strongman--a gentle giant--and two midgets--recalcitrant jerks--Lalouette became their leader, more or less, directing them to build a shelter and hunt for eggs and make a spear and hunt pigs and so on. At night she tells them the story of the Odyssey, unwittingly giving the jealous midgets inspiration of a method of murdering the generous and decent strong man, and their little colony of freaks is wiped out in a spasm of violent death.

A successful little tragedy, understated and sad rather than shocking, as we know from the start that a disaster will befall Lalouette.

"Prophet Without Honor" (1958)

It looks like this one was first published here in On an Odd Note and would be reprinted in 1960 in The Ugly Face of Love.Bohemund Raymond was a hard-drinking London newspaper editor in the first decades of the 20th century. He claimed descent from a leader of the First Crusade who married a Saracen prophetess. (Kersh in this story repurposes the famous story of the Holy Lance at the siege of Antioch, Raymond attributing the dream that revealed the Lance to the Crusaders to his Arab ancestor instead of French priest Peter Bartholomew.) After his death in 1939, our narrator (named Gerald) and his fellow journalists relate anecdotes about their old boss Raymond, in particular his propensity to make predictions. Their talk leads them to reexamine a sheet typewritten by Raymond in the Thirties, a document long thought to be gibberish, but which today they realize is in fact Arabic typed phonetically in the Roman alphabet; it seems that Raymond's ancestor, the Arab prophetess, contacted him from the beyond, because the translated text, by way of cryptic metaphors, predicted the course of World War II and of the Cold War, which, the prophecy contends, will end in 1995. It is unclear, but I guess the prediction is that the world will be destroyed.

Acceptable; the jokes about newspaper people being yelled at by their bosses, hired and fired on a whim, and playing practical jokes on each other are tired and obvious, but not bad--people going to bat for Kersh could convincingly claim the jokes are not tired, but "time-honored classics."

"The Beggar's Stone" (1941)

This one was first published in John O' London's Weekly as "The Stone," and would reappear in three Kersh collections before the Second World War was over; in 1945 it was published in Esquire under its new name, "The Beggar's Stone," accompanied by a dashing photo of Kersh in his uniform in front of a Union Jack.

No comments:

Post a Comment