...Many a time our race has been

Ill-fortuned, plaything of the fickle Fates...

-Statius

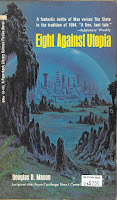

In May, the wife and I drove around the Carolinas, visiting members of her family who have fled the winters of the upper Middle West, taking in art galleries, and shopping at used bookstores. At one such store, Mr. K's, I purchased Eight Against Utopia, a 1970 paperback edition of Douglas R. Mason's 1966 science fiction novel, which appeared in hardcover as From Carthage Then I Came. I bought it largely because of its gorgeous blue cover, but also because it presents itself as steeped in sophisticated literature and Christian thought--the paperback title is no doubt a reference to the war between Polynices and Eteocles, the sons of Oedipus and rival claimants to the throne of Thebes, and I'm guessing the hardcover title is a reference to St. Augustine and/or T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land, and on the publication page we see acknowledgment that Eliot's The Waste Land and Four Quartets are quoted within the text.

I have been reading Eliot lately and so am familiar with The Waste Land and Four Quartets (if you want a taste of the MPorcius "genteel poverty" lifestyle, listen to Eliot read his poems here and here while you hand wash the dishes and fold your own laundry), but it has been years since I have read about Oedipus's unruly children, so I decided to reacquaint myself with their shenanigans by reading some of the classics in translation on my bookshelves. (During the early to mid-1990s, while I was working at a bookstore, I was considering a career as an academic focusing on late 18th-century Britain and its culture, and so purchased and read a bunch of Greek and Roman literature in translation, thinking it would help me get into the mindset of people like Samuel Johnson and James Boswell, whose education and entertainment consisted in large part of these ancient texts.)

If you dare, share my journey through a world of people who seem to spend all their time mixed up in incest, murder, and suicide, or fighting bloody battles against gods, monsters and each other, by clicking below.

Seven Against Thebes by Aeschlyus (467 BC) and some guy (c. 427 BC) (trans. Vellacott)

First up, Seven Against Thebes by Aeschylus in a Penguin edition of translations by Philip Vellacott, which I am pretty sure I have never read before. This drama is a quick read, only like 32 pages in this edition--I read it over the course of a day in which I hung around at the National Gallery of Art and at a table outside DC Pizza, which is right next to Wawa, my go-to place in "The District" for chocolate milk.

The entire play is set in a town square in Thebes, the location of statues of the gods. The first section of the play is sort of amusing—the chorus, consisting entirely of Theban women, panics upon recognizing the approach of the foreign army led by the vengeful Polynices, and they run to embrace the statues and beg the gods for help, to the aggravation of their king, Eteocles, who orders them to calm down lest their panic spread to the rest of the city and cripple resistance to the invaders.

Women! In wartime, or amid the blessings of peace,In the second part of the play a scout returns to the town to report to Eteocles on the movements of Polynices’s army. Thebes has seven gates, and the scout describes to his monarch which hero from the attacking army is in charge of assaulting each gate, complete with an assessment of each's personality and an inventory of his equipment. Some of these champions have pretty innovative kit. One has bells attached to his shield that "send forth a terrifying clang," while another has an image of a sphinx embossed on his shield, "pivoted ingeniously" so that it appears to move; the Sphinx, of course, is the very man-eating monster from which Oedipus liberated Thebes.

Save me from living among them! Give women their own way,

They're bold past bearing; but, once they're alarmed, they double

Every difficulty, in the city and in the home.

After each description of an enemy champion, Eteocles in turn describes the man he is putting in charge of defending that particular gate. The seventh gate of Thebes is attacked by Polynices himself, and Eteocles, over the objections of the chorus, takes up the responsibility of fighting his own brother.

The penultimate part of the play consists of the chorus fretting and retelling in brief form the story of Oedipus. In the final section word arrives that the city has been saved from the invaders, but that in the battle Eteocles and Polynices each struck the other a fatal blow. Their corpses are brought on stage, where their sisters Antigone and Ismene mourn over them. The government decrees that Eteocles will be buried with honors and Polynices’s body left in the wilderness to be eaten by scavengers--"vagrant birds his only tomb," but the sisters and chorus object--"my brother's flesh no hollow-bellied wolf shall tear"--and they insist they will give Polynices a decent burial. (In his introduction to the volume, translator Vellacott tells us that this business with the sisters and the dispute over Polynices's burial was not written by Aeschylus, but added decades later by another writer.)

Seven Against Thebes is short on incident and character and long on speeches and descriptions. It is kind of repetitive, Aeschylus reiterating main themes like the horrors of war and the fact that there is no escaping fate, again and again. (One of the "problems" of this play--and this is a common problem in classical literature and in modern adventure stories which are full of "chosen ones"--is that the characters spend lots of time negotiating with the gods in pursuit of a good outcome and preparing equipment and strategies in an effort to achieve a good outcome, but also repeatedly admit that everything is predetermined by either the gods or the fates and so their efforts are futile.) The play is sort of fun, though no blockbuster.

The Thebaid by Statius (c. 96) (trans. Melville)

Next, I tackled the much lengthier epic, the Thebaid, by the Roman poet Statius; my edition is Oxford World's Classic's translation by A. D. Melville. This thing is like 325 pages of text, with another 40 pages of notes and glossary to remind you where Mercury was born (Cyllene) or the name of Thiodamus's father (Melampus) in case you forgot. (Those appurtenances came in handy--though my underlinings attest to the fact that I read the Thebaid back in the Clinton era, it turned out that I had forgotten almost everything about it.) Statius's epic is split into twelve books, and I read a book a day, which was comfortably manageable and left me time for all the Eliot and Pound material I have been buying.

The Thebaid is a catalogue of fighting, murder, and horror. In Book I, for example, besides invoking the muses and sucking up to the Emperor, describing Oedipus's curse on his sons and the gods' response, Statius relates how Polynices met the first of his champions in his war on his brother. Exiled from Thebes, wandering through the countryside one dark and stormy night, Prince Polynices takes shelter under a palace wall, and then another prince, Tydeus, also seeking shelter from the inclement weather, comes by and they get into a sort of MMA match over this valuable real estate:

First a brief pause for threatening words, then rage

Swelled as taunts flew, and both sprang to their feet

And bared their bodies and stood stripped to fight.

....

Then as they battle, blow on blow is struckThese two hotheads shake hands and make up after the inhabitant of the palace, Adrastus, king of Argos, invites them in. As a bit of pleasant table talk Adrastus tells them the story of Apollo's affair with a Theban princess way back after the sun god had killed the monstrous Python, a serpent whose corpse "scarce a hundred acres could contain." Apollo impregnates this girl, and she is so scared that her father might find out that she hasn't maintained her virginity that, after she gives birth, she gives her son to a shepherd. Somebody should have called the Theban Office of Child Protective Services because this joker is no great shakes as a foster parent--he leaves the baby boy out in a field and dogs rip him to pieces! (If we can't trust this guy with a demi-god baby, how can we trust him with our sheep?) The princess, when she learns of this tragedy, runs to her father for comfort, and the king executes her for failing to keep her legs closed. (Don't worry--the experience of being dumped by Apollo and having her kid turned to Alpo had her longing for death.)

On face and forehead, thick as arrows fall

Or Arctic hail, and knees are flexed to bruise

Soft sides and loins....

Deadbeat dad Apollo returns to the scene of the crime, intent on revenge. He has created a monster in "Acheron's dark depths...

...a girland he unleashes it on the Theban people!

In face and breasts but, hissing ceaselessly,

A serpent rises from her head and cleaves

Her swarthy forehead....

...that frightful fiend

Glided its nightly way from room to room,

And seized from suckling breasts souls newly born,

And gorging bloody fangs, grew fat upon

The grief of parents....

When a hero organizes a posse and this monster is destroyed, Apollo resorts to even more extreme measures until the same hero (an orator as well as a fighting man) convinces him to relent.

Book I alone has enough material for a genius monster movie, and we've got eleven books to go! In Book II, the gods' machinations in pursuit of bringing Oedipus's curse to fruition move forward. Mercury shepherds Laius, murdered father of Oedipus, out of the underworld and like the kids in Peter Pan or Scrooge in one of the hundred film adaptations of A Christmas Carol, Laius is given the power to fly through the night sky! He alights in his old stomping grounds of Thebes, where he stirs up Eteocles's paranoia. One of this former king of Thebes's techniques--to bleed on the current king of Thebes!

Book I alone has enough material for a genius monster movie, and we've got eleven books to go! In Book II, the gods' machinations in pursuit of bringing Oedipus's curse to fruition move forward. Mercury shepherds Laius, murdered father of Oedipus, out of the underworld and like the kids in Peter Pan or Scrooge in one of the hundred film adaptations of A Christmas Carol, Laius is given the power to fly through the night sky! He alights in his old stomping grounds of Thebes, where he stirs up Eteocles's paranoia. One of this former king of Thebes's techniques--to bleed on the current king of Thebes!

The grandfather stood plain. And then he leant

Over that tragic grandson's bed and bared

His throat slit wide with slaughter, and the wound

Welled up and drenched his sleep....

Meanwhile, in Argos, Polynices and Tydeus marry princesses (ancient Greece is like Barsoom--everywhere you go you bump into princesses); at the wedding Polynices's bride wears a cursed necklace made by Vulcan ("Of emeralds that flowered with hidden fire,/And adamant engraved with shapes of doom") and worn by many unfortunate women over the years (Jocasta, mother and husband of Oedipus, for example.)

Eteocles and Polynices had agreed to share the throne, taking turns at one year terms of office, but that first year has elapsed and Eteocles has not sent for his brother, so Polynices sends Tydeus as ambassador to Thebes to demand Eteocles fulfill his promise. Eteocles not only refuses to give up the his crown, but, breaking all the rules of diplomatic etiquette, sends a company of fifty men to ambush Tydeus as he passes the site of the now-vacant lair of the Sphinx on his way back to Argos. In a fight scene which takes up multiple pages and gives Statius an opportunity to describe all manner of injuries horrible (four guys crushed into a single mass under a boulder) and ironically appropriate (a guy who talks too much is speared through the mouth), Tydeus kills 49 of these goofs and sends the last one back to Thebes to bear the news of the massacre.

Book III covers the report to Eteocles of that sole survivor, who then immediately denounces the king and commits suicide before him (Statius portrays Eteocles as an unpopular tyrant), and the histrionic mourning of the families of the 50 dead soldiers.

Eteocles and Polynices had agreed to share the throne, taking turns at one year terms of office, but that first year has elapsed and Eteocles has not sent for his brother, so Polynices sends Tydeus as ambassador to Thebes to demand Eteocles fulfill his promise. Eteocles not only refuses to give up the his crown, but, breaking all the rules of diplomatic etiquette, sends a company of fifty men to ambush Tydeus as he passes the site of the now-vacant lair of the Sphinx on his way back to Argos. In a fight scene which takes up multiple pages and gives Statius an opportunity to describe all manner of injuries horrible (four guys crushed into a single mass under a boulder) and ironically appropriate (a guy who talks too much is speared through the mouth), Tydeus kills 49 of these goofs and sends the last one back to Thebes to bear the news of the massacre.

Book III covers the report to Eteocles of that sole survivor, who then immediately denounces the king and commits suicide before him (Statius portrays Eteocles as an unpopular tyrant), and the histrionic mourning of the families of the 50 dead soldiers.

"Thanks to a wicked monarch's crime, we've lostVenus above and Adrastus below hope to prevent further bloodshed, but the Fates will not be denied and Tydeus and Mars himself stir up war fever in Argos. There is a long scene about augurs, their chief Amphiaraus, who climb a mountain to watch birds and try to predict the future from their movements, followed by an amusing passage in which the most amusing of the Seven champions, the blasphemous Capaneus, says it is a waste of time to try to consult the gods or to prophesy:

Those blameless citizens...."

"...Valour and the swordIn Book IV we get a list of the Argive heroes and battalions as they prepare for the march on Thebes. A little drama is introduced by Atalanta, the famous huntress and foot racer, who begs her kid Parthenopaeus to declare himself a conscientious objector and pass on joining the expedition to Thebes, and by Polynices's wife, Argia; she gives that cursed necklace to the greedy wife of war skeptic Amphiaraus's, a sort of bribe meant to get the seer to sign on to the war effort. (Quite a few characters realize this war is a mistake, but are powerless to turn the course of fate in the face of divine manipulation.) Meanwhile, in Thebes, Eteocles has his own seers, including the famous Tiresias (who, by the way, has a prominent role in Eliot's The Waste Land), try to predict the future by talking to the spirits of the dead. Book IV ends with the Argive army on the march to Thebes; they are delayed by a drought triggered by Bacchus, one of the gods sympathetic to Thebes, but find water before they all keel over.

Here in my hand are gods to me."

It was a local woman, Hipsipyle, an emigre princess from the island kingdom of Lemnos, who guided the Argive army to water, and in Book V she tells her tale of woe. Lemnos didn't have any temples to Venus, so some twenty or twenty-five years ago the love goddess saw fit to punish the islanders. First, she made the Lemnean men lose interest in sex. Then, one dark night, Venus lead the unsatisfied and vengeful women of Lemnos in a paroxysm of misandry which culminates in them murdering their husbands, fathers and sons in their sleep!

Where all seems silent, deadly Venus stands(Whoa, this is not the Venus we all know and love!)

And, dagger drawn, assists the frenzied bands

Bacchus aids Hipsipyle in helping her father, the king, escape the island. When the women come to their senses they think Hipsipyle's father is dead like all the other male Lemneans, so the princess is proclaimed Queen. The Argonauts stop by for an extended visit, and their leader Jason, that cad, impregnates Hipsipyle. In what I am sure is just a coincidence, the crew of the Argo all leave Lemnos right after the Lemnean women give birth. Word then reaches Lemnos that Hipsipyle's father is still alive and kicking, revealing that she is not the legitimate monarch and that she lied to her subjects when she claimed she was right there with them when killing menfolk was all the rage. The princess flees Lemnos, only to be captured by pirates and eventually end up in her current location.

Economists and business people sometimes talk about underserved markets, and if Statius is to be believed, Ancient Greece was an underserved market for responsible babysitters. While telling her story to the anti-Theban coalition forces, Hipsipyle has left the baby boy she is looking after, the son of Lycurgus, king of Nemea, unattended, and, wouldn't you know it, a giant snake, one we are told is as big as Python and is beloved of Jove, slithers by and accidentally crushes the royal brat. (Statius describes how the snake's scales scraped off the baby's flesh--including the face!--and exposed the bones--gotta love those Romans!) Blasphemer Capaneus kills the Godzilla-sized serpent by throwing a spear into its mouth, and then all the local nymphs and fauns mourn the passing of the ophidian monster. While those little weirdos (and Jupiter himself!) are lamenting the demise of their favorite snake, Hipsipyle, King Lycurgus, and Queen Eurydice are crying over the dead baby. A war between Argos and Nemea almost breaks out when Lycurgus moves to pass a sentence of death on Hipsipyle for her crime of depraved indifference, but Adrastus and Amphiarus calm everybody down and then Hipsipyle's long lost sons by Jason appear to comfort her.

As the classicists who make up a sizable portion of the audience of this blog can tell you, in the Odyssey and the Aeneid there are long scenes describing funereal games. Our man Statius follows the example of his models Homer and Virgil in Book VI, describing games held to honor the memory of Lycurgus's dead son. After burning two huge funeral pyres, one for the baby and one for the giant snake (!), a scene enlivened by Queen Eurydice's suggestion that they throw Hipsipyle up on to one of them (good one, Queenie!), the Argives and Nemeans get to the thrill of victory and agony of defeat. The chariot race comes first. Apollo wants Amphiarus to win the chariot race because he is old and could use some happiness in his last years, so, when Polynices is in the lead, the sun god conjures up "a phantom, tressed with snakes, /A horrifying monster, called from Hell" that spooks the son of Oedipus's horses so they crash the chariot and almost kill Polynices. (The whole story of Eteocles and Polynices is about how, whatever you do, the gods or fates are going to determine your destiny.)

For first place Amphiarus is awarded a huge carved bowl once owned by Hercules. King Adrastus presents Polynices (his own daughter's husband, I remind you) with a consolation prize that you just might call "the booby prize"--a young slave girl! Then we have other events, most of which feature cheating or rule bending or poor sportsmanship; a runner pulling his competitor's hair, say, or a guy who brings his own, super-sized, discus to the discus throw.

Book VII has a lot of business about the gods. Impatient Jupiter sends Mercury to get Mars to spur the Argives on to Thebes, and we get to see Mars's iron fortress up at the North Pole and his creepy subordinate minor deities like Panic, Treachery and Strife. Bacchus complains to Jupiter that he is picking on Thebes, and Jove tells him that the buck does not stop here--it is fate, not he, who is driving events. (He may be king of the gods, but he just works here!) Driven by illusions and other devices by Mars and Panic, Polynices and the Argives approach Thebes, set up camp. We get a catalouge of the troops under Eteocles's command, as Antigone, sister of the warring brothers, watches from the city wall. Jocasta, Oedipus's mother and wife, as well as mother and grandmother of Eteocles and Polynices, goes to the Argive camp to beg her exiled son and all these interloping foreigners to abandon the war, without success.

Fighting breaks out in the fields before the city after some tigers of Bacchus's kill Amphiarus's charioteer. Given power by Mars and Apollo, Amphiarus, an elderly man of the cloth, kills lots of Thebans before the predestined time of his death arrives, and, rather than letting him suffer the indignity of being killed by a Theban javelin or spear, the gods open up the earth beneath him and the seer rides his chariot down into Hell.

In Book VIII we get a glimpse of Hell as Amphiarus drives his chariot down there, to the amazement of Pluto and everybody else in the underworld. The Argives retreat and mourn while the Thebans celebrate. Then the next day we get lots and lots of fighting. Statius uses tons of metaphors based on the natural world. There are countless metaphors concerning animals, especially lions (for example, a soldier who kills a bunch of people is like a lion killing sheep), as well as weather and ocean metaphors (the battle lines meeting is like the north wind and south wind colliding amidst a hurricane.) Most memorable is when a guy and his horse are both felled by the same spear cast; as the horse falls on top of its rider Statius compares this to when an elm falls over and the grape vine wrapped around it is also destroyed--the tree is doubly sad because it is falling upon and crushing the grapes it has for so long been supporting.

Tydeus is killed by a spear thrown by Melanippus, but before he expires he kills Mel with a hurled javelin of his own, and then has Capaneus bring him Mel's severed head. The dying prince seizes Mel's head and gloats over it as he dies--his last act upon this earth is to actually eat raw flesh off of his enemy's face! Statius, what is wrong with you?

Book IX starts with mortals and gods sickened by Tydeus's atrocity, and Polynices broken hearted over Tydeus's death. The two armies fight ferociously over Tydeus's body; eventually the Thebans get it and mutilate it. Hippomedon, one of the Seven, mounts Tydeus's vengeful horse and leads a counterattack that carries the battle into the river Ismenus, which is flooding its banks. We got lots of descriptions of discarded bows and spears floating downstream, Thebans hiding underwater from Hippomedon like fish hiding from a ravenous dolphin, and corpses and dismembered limbs being carried out to sea to become the "prey of cruel monsters of the deep." (These Greek and Roman epics always make a big deal out of what happens to dead soldiers' bodies, the Iliad of course features this again and again and we also see Lucan in his epic about the Civil War between Julius Caesar and the Senate make a big deal out of the disposition of Pompey's body after his murder. I guess the ancients think that if you don't get properly cremated, you can't go to the Underworld and will instead wander around the Earth, a miserable ghost.)

Of all the horrible things that happen in Book IX of this 2000-year-old grand guignol, I think this is the most striking:

As the flood snatched, a young lad, Argipus,The ancients thought rivers had associated minor gods, of course, and, when Hippomedon kills a Theban soldier who is Ismenus's grandson, the river itself attacks Hippomedon, leading to his final defeat.

Had clutched an elm; his two fine arms the sword

Of fierce Menoeceus severed; as he fell,

An armless trunk still straining, he could see

Them dangling from the branch high up above.

Hippomedon is not the only of the Seven to die in Book IX; we also witness the last moments of young Parthenopaeus, son of Atalanta. As with Amphiarus, Parthenopaeus is not exactly a great fighting man, but the gods briefly make him invincible so he can massacre lots of hapless Theban extras before his "full thread has spun" and the appointed hour of his death arrives. Diana the huntress is his patron, and she fills the kid's quiver with envenomed "celestial shafts" which never miss. He shoots one guy in the eyes. He shoots another in the crotch. He shoots behind his back Jimi Hendrix-style. Finally this beardless wonder's reign of terror is brought to an end and with his last breath he tells his friend to take a lock of his hair to his mother.

With four of their seven leaders dead, as Book X begins the Argives retreat to their palisaded camp, and the Thebans lay siege to them. Juno sends a message to the god of Sleep, who dutifully puts the Thebans to sleep. As those of you who studied Greek and Latin in school remember, in both the Iliad and the Aeneid there are scenes in which "the good guys" sneak into the enemy camp and murder lots of soldiers in their sleep, and Statius here gives us a similar scene. "Sate your delight/In carnage beyond counting!" the leader of the Argive commando death squad exhorts his fellows.

Having exterminated the Theban force investing their camp, the Argives burst out on their chariots, and ride over a carpet of dead and dying Thebans:

Over the prostrate bodies, weapons, groundto besiege the Thebans in their city. We get descriptions of Argives trying to bust into the city, and the defenders of the town raining missiles of all types down on the invaders, while behind them the civilians panic.

Befouled with piles of dead, and blood and troops

Still breathing, men and horses rushed. Hard hooves

Pounded soft limbs, a soaking stream of gore

Clogged axles. Such a road was sheer delight....

Tiresias, blind seer of Thebes, consults the gods and comes to the conclusion that to save the city the Thebans must resort to human sacrifice! One of Thebes's bravest and most handsome young warriors, Menoeceus, son of Creon, the guy who chopped that kid's arms off, is persuaded to stand on the city wall where all the soldiers of both sides can see him and then kill himself with his sword. I didn't notice that this ploy had any effect on the war, because immediately afterward Capaneus the blasphemer, now the leading figure in the Argive force, climbs up the city walls and begins dismantling the fortifications with his bare hands, throwing the masonry down on the city's defenders as they try without success to shoot him down with catapults! Capaneus begins to boast that even the gods cannot stop him, which irritates Jupiter enough that he kills the upstart with a lightning bolt.

The Argives retreat before the fury of the king of the gods, but as Book XI begins the Furies Tisiphone and Megaera use their hellish magic to keep the war going, and, as they say in movie trailers, this time it's personal. With the Argive and Theban armies severely depleted, who is left to fight but Polynices and Eteocles themselves? Creon, bitter about the fate of his son Menoeceus and coveting the throne of Thebes, gives an impassioned speech urging Eteocles to go out there and get himself killed, while Jocasta gives a great speech of her own, begging Eteocles to refrain from fighting her other son. She contrasts herself with Oedipus--not only has Oedipus cursed his progeny and encouraged this fratricidal war, while she has been fruitlessly trying to stop the bloodshed, but he is spared the sight of the catastrophe that she must witness:

...O my grimShe tries to physically block Eteocles's march to battle:

Husband, how blessed his blindness! My bold eyes,

My eyes, are punished! I must see this day!

...first your arms must bewhile Antigone from the battlements begs Polynices to relent. But the Furies hold the reins of the brothers' passions, and the rival brothers cast aside their mother and sister and finally come to grips, mano a mano, after like 300 damn pages. Polynices narrowly outfights Eteocles, but then stands before his dying brother, requesting that he be handed the crown and sceptre so Eteocles's last sight will be of him as king, giving Eteocles a chance to use his last ounce of strength to fatally stab Polynices through the chest.

Put to proof at home. Right at the gate,

Omen of tragedy, I'll take my stand,

Crime's ghastly spectre. These white locks of mine,

These breasts, you needs must trample, drive your steed

Across your mother's womb, you criminal!

Oedipus emerges from the town, has Antigone guide him to the bodies of his sons so he can lie on them; he looks for their swords so he can kill himself, but his daughter has removed them. Meanwhile, Jocasta kills herself and Creon becomes king of Thebes. (King of Thebes is one of those jobs that everybody seems to want but never seems to work out well for anybody.)

In the epic's final book, Book XII, the Thebans mourn and cremate their dead, but Creon declares that the Argives will be left to rot in the field, prey to birds and beasts, and even puts a guard around the battlefield to keep anybody from giving Thebes's foes a decent burial. The women of Argos, lead by Polynices's wife, princess Argia, arrive to retrieve their sons' and husbands' bodies. Argia, with the help of Juno and Sleep, sneaks by the guards to mourn over Polynices's body--she is soon joined by Antigone, and they manage to drag Polynices's corpse to Eteocles's pyre and, using the still-hot embers there, kindle a fire that burns up the exile's remains.

Meanwhile, the Argive women march to Athens, where they convince King Theseus, just back from outfighting the Amazons and impregnating their queen, Hippolyte, to lead an army on Thebes to demand Creon permit burial rites for the fallen of the Argive army. Theseus easily kills Creon, and the Theban army welcomes Theseus as a liberator. Statius finishes his epic by telling us it took him twelve years to write it, and bragging that students already are memorizing it and reciting it!

If I compare the Thebaid to the other Greek and Roman epics I have read, I'm afraid it has to be accounted the least of them because of its lack of human character and feeling. Achilles and Hector in the Iliad, Odysseus in the Odyssey, and Aeneas in the Aeneid all have interesting personalities and motivations, and they all have relationships with friends, family and women that can affect the reader. Those epics also have memorable supporting characters, like Patroclus, Penelope, and Dido. Lucan's Civil War (AKA Pharsalia) has as characters major historical personages with big personalities and powerful motivations--Julius Caesar and Cato of Utica--and it is interesting to see what spin the poet puts on these controversial figures.

The Thebaid, unfortunately, has a cast of thousands of characters who are each kind of simple and who each have little "screen time"--I was surprised by how few pages even mentioned Polynices and Eteocles. Statius's characters don't have compelling motives that excite the reader's interest or sympathy, and none of them really develops psychologically. When Aeneas abandons Dido to pursue his and his people's destiny, or when Achilles abandons his comrades to death at the hands of the Trojans, the reader is moved by these human stories of men facing moral dilemmas and causing terrible suffering to those they forsake. There is really not much like that in the Thebaid; the characters are puppets of higher powers and lack believable, realistic personalities; horrible things happen to tons of people in Statius's epic, but these people feel like the disposable victims of a slasher movie more than flesh and blood people we might identify with.

On the other hand, the Thebaid is full to bursting with spectacle, presenting an endless parade of hellish monsters and sickening gore, which does have some entertainment value. Again and again I was surprised at the shocking atrocities to which Statius exposed me, the dreadful images he conjured up. I also liked some of the various histrionic speeches, those in Book XI in particular.

Both of these cultural artifacts of an earlier age were a worthwhile read on their own merits, and in our next episode we'll see if having read them helps me better appreciate Mason's 1960s SF novel.

Boswell and Johnson weren't the only ones feasting on ancient texts. Shakespeare "borrowed" from them as did many Renaissance writers and playwrights.

ReplyDelete