"A Gift for Uncle Herman" by August Derleth

Derleth mass-produced short stories to finance Arkham House, the ambitious but not exactly profitable publishing venture of which he was a founder and which he managed for decades, and some of them are pretty shoddy, so I go into the two stories by Derleth in this issue of Strange Stories with a healthy dose of skepticism. However, "A Gift for Uncle Herman" was reprinted in two Derleth collections, 1941's Someone in the Dark and 2009's That is Not Dead, so how bad can it be?

I can say with relief that "A Gift for Uncle Herman" is well-written stylistically, and that the personality of the main character and the depictions of the lesser characters are all quite good. Unfortunately, one of the central gimmicks is a little weak. I like this one, but can only recommend it moderately.

The protagonist is a failed artist, a lazy selfish jerk. He has a job managing the rental properties of his creepy uncle, a scary dude whom he hasn't seen in ages because he and his huge house, which is stuffed full of bizarre artifacts, are so repellant--the nephew conducts his business with his uncle through the mail.

Now in his forties, the jerk feels like he has never enjoyed life. He decides to start embezzling from his uncle, easy enough as the jerk handles all the bookkeeping and never sees Unc the weirdo. But after some months of "riotous living" the nephew gets a letter from his uncle, setting a date for the nephew to come to the queer house to discuss what Unc calls an "error" in the documents he has received from his nephew. Presumably he has realized his nephew has stolen from him and wants to see him to upbraid him or fire him or whatever. The jerk's hopes for the future rest entirely on his inheriting his uncle's estate, so if he gets written out of the will or whatever it will be a catastrophe. So he murders his uncle from a distance via means that are wacky but sort of entertaining--the method of the murder is not the gimmick I am unhappy about.

The nephew buries his uncle and inherits the estate very quickly. Going through Unc's big cluttered house, he finds many books about black magic. One passage, he finds, is heavily underlined, and talks about how wizards always want to prolong their lives or shift their souls to other people's bodies, but the Devil isn't crazy about such behavior and will not support such legerdemain. But there is one circumstance in which you can move your soul to another's body! If you make an appointment with someone, and get killed in the interim, at the time of the appointed meeting you can move into the body of the other person. Sure enough, Unc rises from the grave and takes over the murderous nephew's body the very moment they were scheduled to meet to discuss that "error!"

I like this story and wish Wellman had come up with a less ridiculous way that an evil devil-worshipping sorcerer could take over another guy's body, because everything else in "A Gift for Uncle Herman" is pretty good.

The second Derleth story in the issue appears under a pseudonym, and has been reprinted in three different Derleth collections, so, maybe another winner? Cross your fingers or tentacles, weird fans!

"The Passing of Eric Holm" is an acceptable twist ending story, a little on the silly jokey side, but having as its subject Lovecraftian topics, though overlayed with Derleth's Christian beliefs.

A guy, Eric Holm, has been savagely and mysteriously killed, and Derleth's story describes the investigation--the meat of the story consists of the testimony of a friend of the victim, Jeremy Lansing. Holm was a man with no wife or kids whose hobby, like so many people we read about here at MPorcius Fiction Log, was studying the occult. Holm liked to buy black magic books and try to work their spells; his pal Lansing was often involved in these experiments, which always failed. Holm's final book purchase was a volume about a Christian monk who had learned how to summon and dispel the spawn of Cthulhu. Holm had the wacky idea of testing out some of the spells in the book ("formula," Wellman calls them) by summoning a monster to murder Lansing--Lansing had no reason to fear, because Holm wrote out for him the formula to dispel the monster, should it appear and try to slay him. Or so he believed! In fact, Holm gave Lansing the spell that would send the monster back upon its summoner! So the piscine or perhaps batrachian monster tore Holm into bite-sized pieces and ate its fill.

Acceptable filler; Derleth keeps the humor elements under control and the horror elements are not bad.

"For Love of a Witch" by Manly Wade Wellman

This is a good title, and the illustration accompanying it suggests Wellman's story is about a white sorceress who aids Europeans in the project of seizing the land of Native Americans in the good old 17th century. If this chick had been to college she'd know she should make common cause with people of color in resisting the white patriarchy, but I guess white men, like 5% of the world population, have always been marvelously adept at using their tricknology to bamboozle the 95% into fighting each other instead of forming an intersectional coalition against their melanin-deficient Y-chromosome-infected oppressors. But don't despair--when the Chinese Communist Party's AI has conquered the world I am sure the white man will get what is coming to him and life will be a paradise for that 95% who are today groaning through lives of oppression!

It is 1664 and an English community lives in a fort in North America. This community does not embody our vision of America as the and of limited government and market economics--the leader of the settlement, Nele Foraker, whom Wellman directly compares to John Smith of Jamestown, controls every aspect of everybody's life! Maybe this is justified because the colony is perennially on the brink of destruction from poor harvests or Indian attacks? Maybe it doesn't sting too badly because Foraker isn't one of those aloof leaders who never gets his hands dirty, but is always out in front, working the corn fields more vigorously or fighting the natives more ferociously than anybody? Whatever the case, if I was there I'd be spending every minute wondering why the hell I ever left the green and pleasant land.

As the story begins, the colony is enjoying a period of peace and prosperity, a decent harvest having come in and a treaty having been signed with the local natives. Foraker takes a walk in the woods and comes upon a shocking scene--Indians about to chop off the head of a white woman he doesn't know! He rescues her and drives off the Indians, who claim she is a witch. Back at the fort she tells her crazy story of being the cursed granddaughter of a famous sorceress and of how she was recently accused of "having a familiar spirit," which is punishable by death in England. So she fled Blighty for Dutch America, where they don't prosecute witches, only to find on arrival that the English had taken over the colony of New Amsterdam and witchcraft was back on the no-no list. She fled New York for Foraker's fort.

Indians, intent on destroying the sorceress, attack the fort and we learn all the accusations against the woman are legit as she uses her special powers of detection and prediction and illusion projection to save the English settlement when a sneak attack and then a frontal assault both breach the English defenses. There can be no doubt this woman is a witch! But she claims she is unwillingly possessed by a spirit or something, and this is the first time she has ever intentionally used her powers--she used them because she is in love with Foraker!

Realizing they can't outfight a sorceress, the Indians make peace, but then a new threat arises--it turns out that an English family living in the fort are worshippers of Satan and they have a plan to turn the New World into an entire empire devoted to Satan! Foraker's girlfriend joins them in their weird ceremonies--is she doing so willingly, or is the familiar that possesses her to blame yet again? Captain Foraker attacks the ceremony, and in the fight the witch helps him, saving his life yet again. The family of Satanists exterminated, Foraker and the witch are married.

The Forakers don't get to enjoy married life very long before a witch-finder with a squad of cavalry arrives from England to try Mrs. Foraker for witchcraft! The fact that Mrs. Foraker has foresworn all use of her powers because she loves her husband doesn't cut any ice with this one-man judge, jury and executioner! When the captain defends his wife, he stands himself accused of sorcery, and is laid down under a door piled with one hundred pounds of stones! Luckily the Indians come and kill the witch- finder by surprise and liberate Foraker and the witch. The loving couple abandon the fort to live alone together in the wilderness.

I suggest "For Love of a Witch" is barely acceptable filler. The action scenes are perfunctory and the characters have no personality. The story has no real central spine and doesn't build up to a climax, but is just a series of episodes, Wellman bouncing from one theme to another. All the race and gender stuff may be interesting to 21st-century readers, but Wellman's messages or themes are muddled. Are we expected to admire Foraker for being such a dedicated leader of his people, and then also admire him for abandoning his people for a woman? To denounce witch hunting, even though Satan and witches are real? To sympathize with the Indians, who spend the whole story trying to kill people who are not prepared to defend themselves? Feminists may be thrilled to see the female lead killing a bunch of people, but I'm afraid this story doesn't pass the Borsht test, as our girl is killing people to protect her man.

"For Love of a Witch" was reprinted in the 2001 Wellman collection Fearful Rock, where it appears alongside that story we just read about killer bunnies.

"The Soul of the Cello" by Maria Moravsky

Another story about supernatural phenomena linked to a string instrument? (You'll recall we just read a story by Robert Bloch about a creep using a violin to work black magic on people.) I guess this theme reflects the power music has over people.

"The Soul of the Cello" is a somewhat sappy happy-ending story with a plot like that of a feel-good children's book. The way the plot resolves itself is a little hard to take--the protagonist succeeds without effort or sacrifice on his own part and his trespasses are not punished--but the story is pretty well-written, so I will call it marginally good. (My criticisms of the plot of this story are similar to my gripes about the other Moravsky story we have read, you'll notice.)

I should also note that I thought a cello was a huge thing as big as an adult person but in this story the protagonist tells us "I went to sleep without undressing, with the cello clasped in my arms," and "I laid the voiceless cello on the window ledge" and "one day Mother found it [the cello] hidden among my clothes" and stuff like that so I guess this thing is like the size of a violin. Why not just make a story about a violin, then? I must be missing something.

Our narrator is a Russian Jew, an immigrant to New York, the son of the owner of a used book store. He tells us a story from his Manhattan youth. A musical prodigy, as a kid he made money playing a crummy cheap cello. One day a rich collector gave a free exhibition of his centuries-old cellos. The narrator attended the event and fell in love with one of the cellos, made in Venice ages ago. That night the kid steals the cello, and finds that it is alive, able to play itself! At first the instrument resents being stolen, and its playing is like a cry for help. But its cries are ignored, and eventually it accepts the narrator, who plays it when his parents are out--the thing sounds so great they would know he wasn't playing the lame cello they were able to provide him with the meagre proceeds from the bookstore.

Moravsky does a good job describing how the narrator obsessively loves the cello like an ordinary guy would love a woman, his guilt and fear over being a thief, and the reaction of his parents when they eventually learn that the theft they have been reading about in the newspapers was committed by their own son. This sort of stuff, the stuff of our real lives, lust and guilt and fear and your parents being a pain in the ass, I can get behind. It is the fairy tale goop that follows that dampens my enthusiasm for the story. The ghost of the man who made the cello appears to the narrator and tells him to return the cello, and the cello plays itself and conjures up a magical vision of Venice as it was some hundreds of years ago. The narrator returns to the rich guy's house with the cello--there is a big party there tonight. The narrator plays the cello (actually, the cello sort of plays itself, or is played by the ghost of its maker or something) and the rich guy is so impressed he gives the cello to the thief and vows to promote his career as a world-famous musician. The ghost knew this would happen and that is why it told the kid to return the instrument.

It doesn't look like this fantasy of being born gifted and then winning the support of ghosts and rich people by committing grand larceny has ever been reprinted.

**********

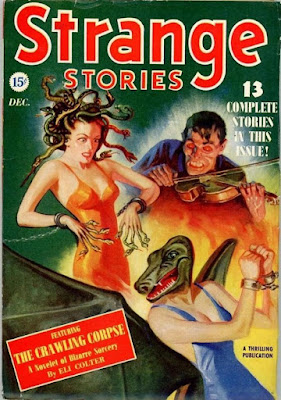

I have a load of criticisms of these stories, but none of these tales is bad, and two of them are well-written enough that I am willing to call them good, so I guess I am recommending this issue of Strange Stories to you, and not just for the wild and crazy cover art.

No doubt we'll be seeing Derleth, Wellman and Moravsky again in the future, likely soon as we continue exploring the weird and the strange of the early 1940s.

No comments:

Post a Comment