(Besides the four stories, I took a look at Otto Penzler's Foreword, in which he draws a sharp distinction between two subgenres which I have basically been conflating in my mind, noir and the private eye story. Penzler argues that the noir, as its name suggests, is utterly dark, pessimistic and nihilistic, while the private detective tale on the other hand has a moral center and its protagonist pursues justice and often succeeds in righting or avenging wrongs. Interesting! I also glanced at James Ellroy's Introduction; I guess that is just a bootless joke.)

"The Lady Says Die!" by Mickey Spillane (1953)

This is the fifth Mickey Spillane story we have read in a week, and it is the best one, being about a human relationship and being pretty tightly written, not just a series of beatings and threatenings and episodes of clue collecting. It has a frame story in which a police inspector meets a wizard of Wall Street at a club and listens to him describe how, without laying a hand on him, he achieved revenge on his life-long frenemy. Most of the text is narrated by this finance guy.

So, these two richie riches grew up together, went to college together, had competing firms on Wall Street. Our narrator is a basically decent guy, but the other guy, the villain of the piece, was lazy and ruthless and was always screwing people over to smooth his way, or just to prove his superiority. He was also good-looking and charismatic, so much so that not only did every woman throw herself at him, but all the people he exploited laughed off his depredations--they enjoyed writing his school papers for him and didn't take it personal when he made their businesses collapse.

The villain stole the narrator's fiancé and then, after they were married, her treated her so callously that she died of a broken heart! This was going too far, and the narrator conceived a scheme of revenge!

The villain is always chasing a new woman, unable to settle down because he is unable to believe any woman wants him for himself and not his money. The narrator has a house on Long Island, and living in the house next door is an angelically beautiful woman; he sees her over the hedge at the same times every day because she follows a very set schedule. He invites the creep over and simply by making sure he lays eyes on this goddess, ensures he falls stupidly, obsessively in love with her. The beauty waves to them, and they wave back, but the narrator never introduces them, making excuses, and the jerk becomes more and more desperate--his whole happiness, his entire hopes for a satisfactory life rest on meeting and marrying this girl!

The woman returns to Manhattan and the villain uses all his resources to try to find her, but only succeeds when his desire is at a manic, feverish pitch, after the narrator, who knows her New York address, gives it to him. Finally, on the high floor of a fancy hotel where she is staying, the besotted swine meets her--and immediately jumps out a window to his death. You see, the woman is "a hopeless imbecile" with "the mentality of a two-year-old."

I like it; it is more like a Somerset Maugham story than a detective thing and has more believable human feeling than the Spillane stuff we have been reading recently.

"The Lady Says Die!" first appeared in Manhunt under the much more appropriate title "The Girl Behind the Hedge.""The Hunger" by Charles Beaumont (1955)

I believe I have read eight Charles Beaumont stories during this blog's life, "The Vanishing American," "Black Country," "Elegy," "Blood Brother," "The Crooked Man," "The Monster Show," "Keeper of the Dream," and "Mass for Mixed Voices." Here comes number nine. "The Hunger" first appeared in Playboy.This is a well-written story about human evil, about how people selfishly, mercilessly, feed off each other, and about human frailty and loneliness. It is also a story about female psychology which a man might be discouraged from writing today in our current feminist age...but maybe as we progress into a trans-affirming age we could protect this story from cancellation by saying it is evidence Beaumont was "born in the wrong body" or "gender non-conforming" and thus "The Hunger" is not a retrograde work, but a pioneering one! (Bolstering our defense is the fact that "The Crooked Man" is a story that expresses sympathy for homosexuals.)

Julia is a skinny virgin in her late thirties who lives with her older curvaceous sisters, widows, in a town of 3,000. Julia is quiet, bookish, unhealthy, her sisters robust and meticulous about their housework and great lovers of gossip and chat, and they have a lot to gossip about nowadays, because their little town is being haunted by a serial killer! The killer is, apparently, an escaped mental patient who raped and murdered a girl before he was involuntarily committed, and has raped and strangled three women in the town so far and is still on the loose.

Beaumont's story is pretty misanthropic, portraying the older sisters and the town in general as enjoying the drama that comes from being under siege by a rapist strangler. The women love to talk about the crimes, speculate on the killer's next victim, use the killer as evidence in their arguments that all men are sex mad. The men in the town enjoy going out every night with torches and firearms to hunt the murderous fugitive. The story includes passages in italics that depict the killer's furtive movements and feverish thoughts; his desire to rape and slay is described as a hunger, and I think that we are supposed to consider the similarity of his hunger, which he appeases by violating and destroying people, to the hunger of most of the townspeople for both excitement, which is also appeased by the killer's atrocities, and for a bloody revenge on the killer.

Julia, lonely and horny, begins to identify with the killer, to think his outrageous behavior is the result of his loneliness. Late one night she puts on her best dress and sneaks out the window, telling herself she needs a breath of fresh air but actually hoping, though she only half admits it to herself, that she will meet the rapist and he will have sex with her. Maybe she can reform him by giving him her body willingly?

Pretty good, whether or not you take Beaumont's theories about human psychology seriously. "The Hunger" is the title story of a Beaumont collection printed in 1958 and would go on to appear in several horror and mystery anthologies.

"For the Rest of Her Life," in style, feels like an old-fashioned novel; I guess that is the "romantic" and "Fitzgerald" stuff from the intro. There are long somewhat abstract descriptions of what people look like ("There was something of youth hovering over and about him, and yet refusing to land in any one particular place"), extravagant poetic dialogue ("I only know one thing...I want to see the stars again at night, and not just the blackness and the shadows"), obvious symbolism (a woman's wedding ring is removed, it falls on the floor and rolls away, and a guy accidentally steps on it, warping it, just like her marriage was warped) and elaborate theories about relationships (Woolrich expends lots of ink distinguishing an "attachment" from a true love affair.) I can't quite decide whether this style, which one could easily call "overwriting," weakens the story or not...it is not exactly bad--it is not irritating or boring--but it feels a little much, makes the story longer without perhaps adding any real content or atmosphere, though perhaps some readers consider this stuff "good writing" and enjoy it for its own sake. The car chase scene is legitimately good, and not at all overwritten, so I guess Woolrich knew when the time had come to tone that stuff down.

The plot of "For the Rest of Her Life" is not bad and I am giving this story a thumbs up. A young American woman meets a youngish American man in Italy and they develop a pleasant friendship ("attachment") and then lose track of each other when they return to the U.S. When they meet again they realize how much they have missed each other and decide to get married, which begins a life of pain and horror for the woman--her new husband is a sadist who pulls capers like murdering strangers' pets and tortures her to get his rocks off!

Wife stays in the house on Long Island all week while hubby stays in Manhattan, where he runs an art gallery, and comes home to torture her on weekends. (She is too embarrassed to tell the cops or anybody else about her nightmare of a life--this is the perfect story for feminists who want an illustration from fiction of how social mores and the indifference of the authorities enable violence against women and trap women in dreadful situations.) She becomes friends with a guy and this guy figures out she is married to a sadist. Oddly enough for a middle-class woman who travels to Europe, she has never even heard of sadism, so her new buddy lends her a book called The Marquis de Sade: The Complete Writings. They fall in love, and he tries to help her escape the sadist, leading to a good fear sequence and then a good car chase. The car chase ends with a crash; her new love is killed, and she is paralyzed from the waist down and after a long stay n the hospital is surrendered to the care of her husband, who will, we must assume, torture her to achieve sexual satisfaction for the next 40 or 50 years.A good horror story, and another of today's stories that reminded me of Somerset Maugham. "For the Rest of Her Life" first appeared in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine and was reprinted in a 1978 collection with an introduction by Harlan Ellison.

"Mefisto in Onyx" by Harlan Ellison (1993)

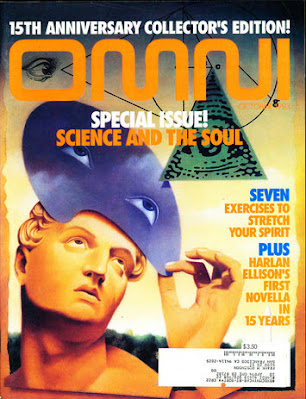

Speak of the Devil! Harlan Ellison's "Mefisto in Onyx" first appeared in Omni, heralded on the cover as his first novella in 15 years. (Ellison had good PR.) It won a Stoker and a Locus award, and a few years later a revised version was published as a chap book. We are told the version here in The Best American Noir of the Century is the revised one, not the Omni one.I thought today's audience might find Charles Beaumont's story "problematic" because he was a man and portrayed the psychology of the female in a light far from the most favorable, well, this Ellison story here threatens to be in deeper doo doo still--in "Mefisto in Onyx," Ellison writes in the voice of an African-American Rhodes scholar!

Rudy is no ordinary Rhodes scholar, but one who has psychic powers! Our narrator can read minds and even edit the contents of others' brains, an ability he uses to control them like puppets. Rudy is also a long-suffering martyr; he refuses to use his powers for financial gain, and has trouble keeping a job or making friends because people--white people, essentially--are all such jerks that knowing what is in their minds is so depressing he can hardly deal with people, and when he does build relationships and people find out he has psychic powers they try to exploit him, to use his powers to further their careers.

As we perhaps expect from Ellison, the entire story is written as if he is sneering, whining, or yelling. Upon the reader is unleashed a tsunami of breathless run-on sentences as well as staccato bursts of monotonous repetition, all of it characterized by self-importance and self-pity and peppered with mundane conventional jokes, brand names, and cultural references both vintage and up-to-date, both middle-brow and high-brow. Oh yeah, and many variations of the n-word, that word we of 2022 are afraid to say, that word we of 2022 are afraid to type! Ellison's text is like the "rants" of a stand-up comedian--long-winded, repetitive, exhausting.

Every character in "Mephisto in Onyx" is extreme, is the ne plus ultra of his type. Rudy is a martyr genius with psychic powers. The violet-eyed female lead, Ally, is the world's greatest lawyer as well as a divorcee and a rape victim who is estranged from her parents. And then we have our third character, the world's most horrifying serial killer, a charismatic blue-eyed blonde who claims that, at the orphanage where he grew up, he was bullied for being fat and saddled with the nickname Spanky.

The plot. The narrator's best friend, Ally the white woman super-lawyer, is a DA in Alabama and has just shocked the world with her legal maneuvering in prosecuting Spanky, the world's killingest and most perverted serial murderer. But Ally has fallen in love with this monster, and come to believe he is innocent. She wants Rudy the psyker to read the convict's mind to see if he really is innocent. The conversation in which she makes this request and Rudy agrees to it as they sit in a burger joint is page after page of tedious dialogue and description, with all kinds of tangents and asides. She spills ketchup...they move seats...some other customers come in...blah blah blah. Ellison spends an entire page describing Ally's attaché case because it exemplifies her character. Reading this thing was taking forever, and my heart sank when I finished the mind-numbing page on the Irish leather bag that was understated and thus proved that Ally had nothing to prove because it wasn't as fancy as the bag a person who had something to prove would carry and saw I had only hacked through like a dozen pages of this boring story and had like 30 more to go.

|

| Representative sample of prose in the winner of the 1993 Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in a Novella and the 1994 Locus Award for Best Novella |

We escape the burger joint halfway through "Mephisto in Onyx." In keeping with the story's extreme nature, the rainstorm that Rudy has to drive through to get to the prison is so ferocious he drives off the road into the ditch six times. But good things happen on the drive as well--during a lull in the rainfall he smells flowers and they smell so beautiful he cries.

Rudy gets into the prison to meet with the serial killer by claiming he is a lawyer and a friend of the President of the United States. As readers may have predicted, this guy is also a psyker! (How else could he have gotten the lawyer who was intimately familiar with his dozens of murders to fall in love with him?) Spanky the mass murderer uses his powers to convince Rudy that he is the real serial killer, and Spanky is freed and our hero is put on death row! During the year that passes before he is to be executed, however, Rudy figures out what is going on, expands and perfects his mental powers, and at the last moment, as he sits on the electric chair, shifts his consciousness from his black body to the white body occupied by the killer (who has been moving from body to body for centuries) and traps Spanky in his (Rudy's) cisbody--when the lethal voltage courses through Rudy's old residence, the new inhabitant, Spanky the killer, is destroyed. Now that Rudy inhabits the handsome white body that diabolical psychic powers have already hypnotized Ally into loving, he can live happily ever after.

The bare outline of the plot (there are two psykers in the world, a good one who sees his gift as a curse and an evil one who exploits people with his powers, and when they meet it is a fight to the death!) is not bad, but the style, pacing, atmosphere and tone of "Mephisto in Onyx" are all annoying and enervating--reading this thing was an exasperating chore. This is a ten-page story stretched out to over 40 pages by turning every last aspect of it up to 11, by hammering away at the same points again and again, and then adding in a lot of extraneous passages on top of that.

So, how did "Mefisto in Onyx" win those awards? Was it name recognition? Did its anti-racist and woe-is-me themes appeal to SF fans' sense of moral and intellectual superiority and feelings of grievance (consider the popularity of Slan in its day, more recently of the X-Men, and (I have to go by hearsay here because I haven't read it or seen its movie version) Harry Potter more recently still--SF fans think they are better than everybody else and that everybody is mean to them.) Or do people actually enjoy Ellison's feverish and sanctimonious stand-up comic style?

I have to diverge from the wisdom of the Locus crowd and give "Mefisto in Onyx" a thumbs down.

Another question we might perhaps ask is why is this story with its happy ending in this book of noir stories? Didn't Penzler tell us in the Foreword that noir stories end badly? Well, my theories about name recognition and devotion to anti-racism apply here as well, but a more sophisticated take may be that Penzler and Ellroy don't consider "Mefisto in Onyx"'s ending to be a happy one--Rudy's experiences have not only proven that America is irredeemably racist, but have corrupted him, and he and Ally are going to spend the rest of their lives together in a relationship based on coercion and deception.

**********

Serendipitously, today's stories share the theme of how women--to their peril!--are sexually attracted to charismatic bad boys. I'll leave to you the decision of whether this theme represents ancient wisdom or merely the story the patriarchy wants you to hear.

There have been some rough spots, of course, but I have enjoyed this recent series of blog posts about stories in which people get tortured, get beaten up, get murdered or just cut out the middle man and commit suicide, if only because it satisfied some of my curiosity about what was going on behind the striking covers of all those detective magazines and paperbacks. If I live long enough, I'll read all of these authors again, but first we'll be exploring a book of fantasy by one of our favorites which just might be even more twisted and perverse than all these detective stories!

Not surprised that Ellison's 'Onyx' turned out to be an overrated dud......too much of his stuff in the 90s suffered the same problem.....

ReplyDelete