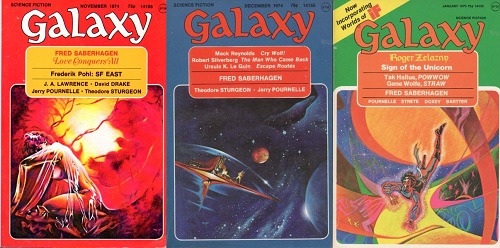

"Killing? How can you call it...if I dig up an acorn am I killing an oak tree?" But it was no use. He didn't want to argue with Ann, and anyway it would really be impossible. She lived in a reality so far from the generally accepted one that Art could see no place to start. At least he couldn't now, not after a day of strain and wife-chasing and rioting and Black Russians.Advertising works! At the end of my Ace paperback of Poul Anderson's Flandry of Terra we saw an ad for Fred Saberhagen's Love Conquers All, a novel first serialized in Galaxy at the end of 1974 and the start of 1975, then published by Ace in 1979. The book was reprinted in 1985 by Baen with an absurdly generic and lackluster cover. That Baen edition of Love Conquers All, which, according to the publication page, is "Newly revised," is available at the internet archive, and, thanks to the ability of advertising to reach across four decades, I just read it on this very computer screen.

It is the future of underground maglev trains that carry you from California to Illinois at supersonic speeds, of self-driving cars, of mass unemployment and universal guaranteed basic income and scads of other government handouts. For close to a century mainstream society has embraced, and the government and other establishment institutions strongly encourage, sexual promiscuity. The most popular religious institution is the Church of Eros, and reproductions of Caravaggio's Amor Vinicit Omnia are hanging all over the place. Open marriages are the norm. People walk around practically nude. Government regulations make sure performers on TV shows don't show too little skin. Women who conceal their breasts and make themselves sexually unavailable are considered to be selfish antisocial jerks. Average people consider pregnancy an ailment to be got over, and it is illegal to have more than two children; third children are called "superfluous" and "unwanted" because, even if their parents want them, they are "unwanted by the world."

Behind all these pro-casual sex and anti-baby laws and social mores lies fear: fear of the neuroses believed to be the consequence of sexual repression and frustration, but more importantly the fear of the starvation and cannibalism that may result from overpopulation. But, in the time period of the novel, culture is evolving, with a counterculture developing that is curious about chastity and monogamy, a growing network of Christian churches, and an underground that helps women who have become pregnant a third time escape mandatory abortion.

We might call Love Conquers All a sort of switcheroo story, seeing as it depicts social developments the reverse of those that took place over the course of Saberhagen's life. At the start of the 20th century the people who set the tone for culture and society, the establishment or the elite or the mainstream or whatever you want to call them, were, at least rhetorically, against sexual promiscuity and abortion and supportive of monogamous marriage, and people who were sexually promiscuous, had or provided abortions, and were felt to have betrayed their families or had unconventional attitudes about sexual relationships, ran a real risk of social or legal sanction. As the century ground on, through technological and political changes and horrendous wars and revolutions, attitudes about sexual promiscuity and abortion and the family changed, with more and more people and institutions tolerating or even celebrating sexual promiscuity, abortion and the loosening of traditional family ties and new forms of family structures. In Saberhagen's novel here, for as long as anyone living can remember, the establishment has been enforcing sexual promiscuity and abortion as legal and social norms, but the attitude of ordinary people is changing, reflected in growing interest in sexual restraint and the popularity of TV shows about life in the Victorian era, while radical movements that consider a fetus a person grow in size and influence.

Love Conquers All has some wacky satire elements. Men in this casual-sex-approving society grope and pinch women as a greeting or farewell, and people snap "chastity" or "triplets!" when in distress like a 20th-century person might utter "fuck," or "damn!" Exposed to nudity and casual sex almost constantly and discouraged from restraining their sexual impulses, many people find concealing cloaks to be sexually arousing (mainstream mores condemn such opaque attire as obscene--clothes worn for warmth or protection are transparent) and fantasize about monogamous sexual relationships in which desire is held in check; hard core middle-class counter-culture types indulge in steady relationships with lovers they refuse to touch, finding restraint more thrilling than the casual sex with strangers that is the norm. One minor character is a psychologist, and In a parody of Freudianism he is certain that human actions are driven by subconscious urges to be celibate, that everyone is tempted to not have sex, and that it would be healthy if people gave in to their socially unacceptable desires to avoid sex. One scene is I guess a joke from Chicago-born Saberhagen for all you sports fans out there--unemployed people are paid per inning to go see the Cubs lose baseball games.

While these broad satirical elements are present, Love Conquers All is written and structured like a mainstream novel, not like an exercise in humor or a genre adventure tale, and I think we are expected to take everybody's emotional tribulations seriously.

The plot--TLDR version:

A guy who more or less is OK with the current pro-sex anti-baby regime discovers his wife has gone on the lam because she is preggers with baby #3 and wants to keep it. He chases after her, hoping to find her and convince her to do the right thing and have their child sucked out of her body piece by piece by a robot. He meets lots of people and has lots of discussions and in the final scene ends up fighting the police to save their third child--it is not certain they will succeed, but we are given indications that escape from mandatory abortion is likely.

The plot--long spoilertastic version:

Art Rodney is an electronics expert living in Cali, now working in industry after a period teaching at a college; he is also a chess master (SF people love chess.) He is married to Rita, and they have two kids. Rita has some radical ideas--she is reluctant to have sex with other men, for example. Her brother George lives in Chicago, and George's wife Ann is really out there, wearing clothes that cover her breasts, for example. One day Art comes home to find a note--Rita is on the lam because she is pregnant with a third child and knows if the government finds out about her delicate condition she will be forced to have an abortion. Art may be an ordinary guy who thinks of an abortion as a procedure no more remarkable than having a hangnail removed and considers it more kind to destroy his unborn child than to condemn it to a life of social stigma as a "superfluous" person, Rita is determined to keep the child.

Hoping to track down Rita and talk some sense into her, Art takes the subterranean super train to Chicago to see George and Ann. The train's journey is interrupted by a riot on the surface at a Christian monastery; a pro-abortion mob has attacked the monastery in response to rumors about what the Christians are doing in there. The train is evacuated and the passengers join a group of people fleeing the violence, including a young woman named Rosamond; Art has sex with Rosamond to comfort her.In Chicago, when a government agent, searching for Rita, whom the Feds know is carrying an illegal child, catches up with Art, our hero gets an inkling of what was going on in that monastery. Pro-baby activists have come up with a means of removing quite young fetuses from pregnant women and preserving them for later birth in natural or artificial wombs. Because the mandatory abortion law only allows the government to abort fetuses that are less than nine months old, if a fetus is frozen and hidden from the Feds long enough, it is accorded the rights of a citizen and cannot be casually destroyed, even if it is only a few months old biologically.

Rita has left the kids with George and Ann, who support Rita's bold and risky decision to keep her baby, and escaped into the pro-baby underground. George, a karate instructor with a black belt, has contacts among the working and lower classes, and Saberhagen gives us detective fiction scenes in which George and Art travel to the seedier parts of town, and we get an idea of how much crime and social strife (the unemployed who live on the dole resent the employed, for example) the world faces. We also get acquainted with Fred Lohmann, Ann's brother, a kid just out of high school. Fred wants to work for George at George's dojo, but he's not a good enough a fighter yet, and probably won't become one, as he is sort of lazy and dishonest. Through Fred's eyes we see what life and relationships are like for young people in Saberhagen's pro-easy sex, anti-procreation world; a flashback to the dawn of George and Ann's relationship serves a similar purpose, but while George has become a responsible small businessman and devoted family man, Fred becomes a dangerously violent criminal.

Art gets mixed up in a riot when counter-protestors from the Gay League, homosexuals and transsexuals who support the establishment, clash with a pro-chastity demonstration by a group called The Young Virgins. Knocked unconscious, Art wakes up in a secret facility where the anti-abortion activists preserve fetuses; a doctor who is also a Christian priest patches up Art, and they have an argument about abortion after Art by chance stumbles onto a three-month old fetus floating in a life-sustaining chamber, which gives Saberhagen an opportunity to describe how the tiny little girl has very human hands but a head and "gills" that remind Art of a fish.

After he leaves the secret medical facility, Art is arrested because he's been seen with members of the anti-abortion/pro-monogamy underground. He gets released when he mentions Rosamond to the cops--it turns out Rosamond's father is a bishop of the Church of Eros. Art and this guy have a philosophical discussion, and then Rosamond, who sympathizes with the underground, takes Art to see the man she is having a chaste romantic relationship with, a psychologist, thinking he may be able to help Art find Rita. This headshrinker Art to his father, a rich man whose tendrils extend into all sorts of underground and illegal enterprises. When this rich guy learns about Art's hope that Rita will have an abortion to escape legal jeopardy, he pulls strings to help Art out, or so he thinks. Due to tragic coincidences and and misunderstandings, Fred is hired to steal Rita's frozen baby from the cooler in which it is living in suspended animation. George slays Fred's partner in crime in hand to hand combat, and Art, signifying an epiphany and act of redemption brought on by love for his wife, runs off with the cooler, knocking over the detective he met when he first hit Chicago, endeavoring to get to a facility that will protect his unborn son from the government. While we don't see Art make it to the facility, and can't be positive that Rita, George and Art will escape conviction by a jury of their peers on the charges of illegal baby-making and thug-killing, Saberhagen offers clues that lead us to expect this welcome outcome is likely.

***

While a few of the most critically acclaimed (I'm thinking of Gene Wolfe and R. A. Lafferty here) and most influential (like J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis) SF writers are committed Christians, most SF writers are religion-hating leftists or libertarians, so a SF book that takes seriously arguments against abortion is a rara avis. Taking a different tack like this is a good idea, but unfortunately Saberhagen, whom wikipedia tells me was a practicing Catholic, is not as talented or innovative a writer as fellow Catholics Wolfe or Lafferty, and Love Conquers All is pretty mediocre when it comes to style and plotting.

The novel is too long. Individual scenes are too long, and some long sections are pretty superfluous; for example, the flashback to George's first meeting with Ann, Fred's job interview with George, and a meeting between the head of the Chicago Family Planning department and the head of the Gay League. Scenes with George featuring karate are, I guess, supposed to add violence and excitement to the story, and the scene of the homosexual activist's meeting with the government bureaucrat has an expository purpose (they talk about overpopulation) but since the early karate scenes don't involve Art or Rita, and we know George is not going to get killed or maimed, they don't really add any tension or thrills, and the exposition in the scene with the leader of the Gay League is redundant--we have already been subjected to exposition about overpopulation. (The fight scene at the very end is admirably brief, the stakes are high, and Rita and Art are there, so that scene is a success.) If Saberhagen was able to write these unnecessary scenes in such a way that they were funny or moving or included beautiful images or striking metaphors, we might not mind that they do not serve the plot and slow the pace of narrative, but Saberhagen's style is merely competent, not inherently enjoyable. Saberhagen's ideas may have been better served in a shorter form--maybe the Galaxy version is substantially shorter?

Another of my gripes with Love Conquers All is that Art is not a strong character--he is buffeted hither and thither by others and by luck. We are told he is an electronics expert and a chess master but does this stuff ever matter to the story, does it ever add interest to the novel's 270 pages? No, it does not. It is Rita who should have been the main character, because it is Rita who experiences the big emotions and makes the big decisions and takes the big risks: she loves her unborn baby and so is determined to save it, but her efforts to do so put her at odds with her husband, whom she also loves, and put herself, her husband, and her kids at risk because she could wind up imprisoned by the government or even harmed by rioters or criminals.

(I recognize that the fact that Art sort of lamely goes along with his corrupt society and other people he knows until the very end when he makes a big decision and explodes into activity, risking it all to do the right thing, suits the story's Christian themes, but it doesn't make for an exciting extended narrative.)

Merely acceptable. Obviously you should read this if you are interested in portrayals of abortion in SF, SF by Christians, or specifically in Fred Saberhagen's career and thought, but I doubt it is the type of thing that conventional SF readers will be thrilled by.

**********

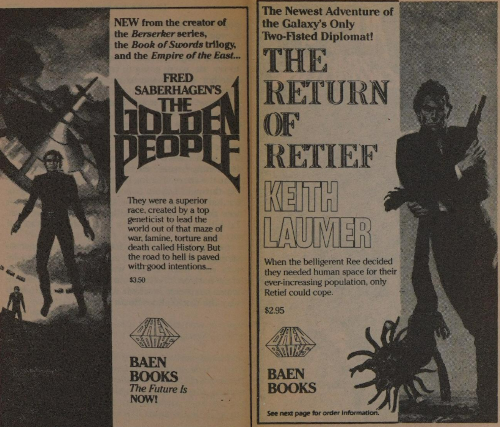

The last eight pages of the 1985 edition of Love Conquers All available at the internet archive consist of a three-page excerpt from Poul Anderson's Game of Empire and four pages of ads. One is for another Saberhagen novel, one about a genetically engineered superior race; it seems this, like Love Conquers All, is a revised Baen edition of an earlier work of Saberhagen's. The illustration suggests the superior race is of people who can fly, which I have to admit is a pretty clear sign of superiority.

One ad is for one of Keith Laumer's Retief novels. Remember back in 2019 when I read the collection Nine by Laumer and its introduction by Harlan Ellison? I should read more Laumer soon.

The next ad is for John Willett's Aubade for Gamelon, which I guess is another superior race novel. There is a rose on the cover, which, frankly, doesn't strike me as so superior--I mean, I have a rose bush in my own yard, and I am not exactly a superior specimen. This novel is hilariously blurbed by Robert Bussard, whose bio on the ad is longer than the totally generic and uninformative blurb he provided. Sad.

The last ad is for Killer by David Drake and Karl Edward Wagner, a book I can actually recommend, as I read it years ago and enjoyed it. A good violent adventure/horror story set in ancient Rome.

**********

Thank you for scrolling to the bottom of a post on my blog, which has been identified by Twitter (or its partners!) as unsafe.

In the late 1960s, Keith Laumer was my favorite SF writer. I was a big fan of his Retief stories. And I enjoyed his Imperium novels. Laumer suffered a stroke and his writing was never the same.

ReplyDelete