Today, at the internet archive, in scans of 1935 and '36 issues of Astounding, we're going to read three more of John W. Campbell, Jr's Don A. Stuart stories. All three would reappear in the 1948 Campbell collection Who Goes There? as well as the 2003 collection A New Dawn: The Complete Don A. Stuart Stories.

"Night" (1935)

"Night" is the sequel to "Twilight," which we read back in 2020. "Night" is a sense-of-wonder mood piece--there really isn't much story here, just long descriptions of how, billions and billions of years from now, everything is really really cold, everything is really really old, and everything is really most sincerely dead, with added descriptions of the characters' disturbed and oppressed psychological states.The frame story, narrated by one guy, describes a twentieth century test flight of an aircraft with the world's first anti-grav motor. The plane crashes and Campbell describes the psychological states of the men who rush to the crash site and find the wrecked plane, but no pilot. The next day the pilot suddenly appears by the crash site. He tells the main story, taking over the narration, relating how, somehow, the anti-grav device unexpectedly sent him, but not the vehicle, bazillions of years into the future, when most of the stars in the universe are dim or dead and the Earth is so cold much of the air sits frozen on the surface as snow. He explored a dead city, full of self-repairing, self-replicating, machines which continued operating for millions of years after the last human died, and finally fell inert millions of years ago when the universe ran down so no more energy was available to power them. We hear how being in this unprecedented predicament affected the pilot's feelings.

The machines on Neptune were still operating, having been built to higher tolerances. The pilot contacted them and they showed him around a city on Neptune; these machines were dedicated to learning all they could about the universe, but having learned everything over the billion years since mankind expired, they were now basically waiting for their own power to run out.

Then, in some unexplained fashion, the pilot got back to 1900s.

Each individual paragraph of this story is good, the images and poetic sallies and metaphors work, but since there is no actual story it feels kind of long and tedious. And unlike some of the other stories we've read by Campbell that appeared under the Don A. Stuart pseudonym, there is no counterintuitive argument being made or depicted. Maybe I have Edgar Rice Burroughs on the brain, but a piece of fiction twice as long as this, with all the same text but with additional text in which the pilot meets a princess and has to fight the barbarians or revolutionaries ranged against said princess, and in which the princess's people are commies or slave owners or cannibals or have no incest taboo and the princess and the pilot argue about the counterintuitive utility of these disgusting practices, might have been more compelling.

(Remember when there was that craze in which people would interpolate paragraphs about fighting dragons or zombies into Jane Austen novels? Did anybody actually read those?)

On the low end of acceptable.

Besides Campbell collections, "Night" has reappeared in a multitude of anthologies edited by people like Sam Moskowitz, Brian Aldiss, Robert Silverberg, and Isaac Asimov, and has also been translated into several foreign languages. I guess the SF cognoscenti really like these sense-of-wonder mood pieces that dispense with the sex and violence that are the draw for so many of us genre fiction readers.

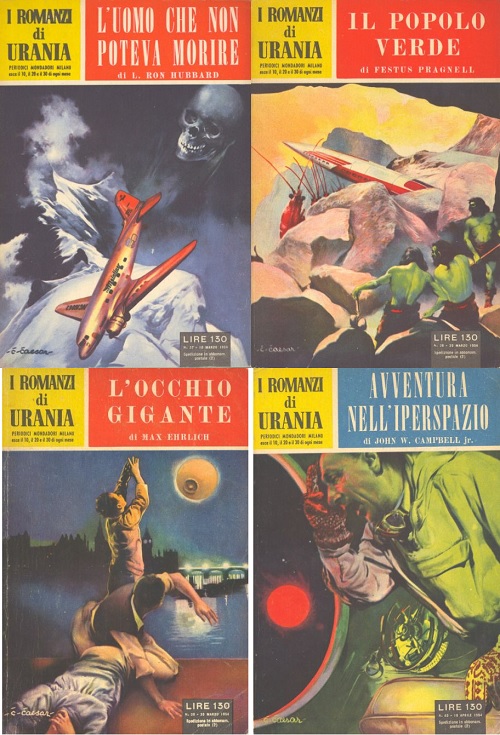

"Elimination" (1936)This one has mostly been confined to Campbell collections since its debut in Astounding, but in 1953 it was included in an Italian magazine and a British magazine. Mama mia, guvnah.

This story has the sot of counterintuitive argument we have come to expect from Campbell--in "Elimination" the point is argued that some revolutionary inventions that you might expect will radically improve human life should be suppressed because of the dire unforeseen consequences they will have. In the frame story, a young inventor goes to an older man, a family friend who is a patent attorney, with his scheme that will dramatically cut the cost of storing and transmitting energy. The attorney advises him to abandon this new invention as it will destroy the financial system, the bedrock of modern society. Then the patent attorney narrates the main story, which illustrates his point about revolutionary technologies having disastrous consequences unforeseen by their inventors.

The attorney knew two inventor dudes who came up with a chronoscope, a device that could see the future! But the future is not fixed, so this machine shows the many possible futures; the degree to which a future is likely is distinguishable by how clear the video of it is--the image of the patent attorney sitting in his office ten minutes from now is very sharp, but the image of the remote possibility of the patent attorney getting killed by an assassin is very faint. The likelihood of various futures coming to pass changes over time, as you would expect, and the two inventors try to make decisions that will improve their future lives, but things don't work out very well, and after various tragedies the survivors decide to destroy the chronoscope and the records that might help anybody else build one.

This story convinces the young inventor to abandon his energy efficiency enhancing invention.

I'm calling this one barely acceptable. The story of the chronoscope is very complicated--I couldn't wrap my head around how the two guys were sending themselves messages across time and trying to manipulate the future via their choices and all that. Either Campbell's story doesn't make sense, or I wasn't smart enough to get it, or I was too lazy to really wrack my brain trying to figure it out (shifting the blame from my own inadequacies, I will also add that Campbell didn't offer a plot or characters compelling enough to inspire me to do that wracking.) The frame story is also pretty questionable--sure, new inventions that change society can bring new problems along with their benefits (every day I'm hearing that the internet is driving teenage girls insane) but I don't think Campbell presents a good illustrative example here. Wouldn't more energy mean more financial activity as more businesses could get off the ground and more people would need loans and more people would be able to pay back loans, thus strengthening the financial system?

"Frictional Losses" (1936)

This story begins in post-apocalyptic New York City, as an old man, Hugh, and his young companion, Ban, search the ruins for old radio tubes and other electronic components. In expository dialogue we learn the history of the war between aliens and the Earth that occurred thirty years ago. One hundred alien space ships attacked Earth, wiping out Africa, Asia and South America, but being finally defeated by Japan, Europe and the United States. (Perhaps most interesting about the story is how Campbell depicts the Japanese pioneering the use of kamikaze--though he doesn't use that word--planes against the aliens.) All one hundred alien ships and their crews were destroyed, but in the process every city on Earth was reduced to ruins and today the Earth population weighs in at a mere two million souls, most forced to live a parlous existence as scavengers and subsistence farmers.Everybody knows that a second alien expedition is bound to arrive eventually and finish off the human race. People like Hugh, a scientist, are struggling to rebuild mankind's technological and industrial capacity in order to meet this attack, while others have given up hope and resent people like Hugh who appear to be doing no productive work and are being fed and clothed by the backbreaking labor of others.

In the end, of course, Hugh's scientific tinkerings pay off. He figures out how to project a ray that eliminates friction. When the ray plays upon an item held together by friction, like clothes or a house of nailed wooden planks, they fall apart into individual threads or a pile of planks and nails. Aiming the ray at a mountain causes an avalanche.

Because Hugh and Ban have been tirelessly maintaining one of the last working radio sets and are in communication with other bands of survivors across America, they are able to send the plans of the anti-friction ray projector around the world, so every band has one when the second alien expedition arrives. With the defeat of this alien invasion force by the new ray, the human race regains its confidence as well as usable alien technology and begins the climb back to a modern industrial civilization.

Of the three stories we're talking about today "Fictional Losses" is the most conventional, with its straightforward plot and pro-science message. Acceptable. It has been ignored by anthologists and magazine editors, with one exception--in 1954 it appeared as a serial in an Italian magazine, spread over four weekly issues.

**********

These stories aren't great; one is pedestrian, and the other two are ambitious but have flaws that diminish their ability to engage an audience (at least the audience here at MPorcius Fiction Log that knows quite little about science and is always looking for thrills and chills.) But I suppose they are good illustrations of the concerns and aspirations of the 1930s writers of the science fiction that is actually about the hard sciences--all three of Campbell's tales have main characters who are scientists or explorers using cutting edge technology; one tries to blow your mind with speculations about the almost impossible to imagine far future; one tries to blow your mind by arguing a totally counterintuitive point about science and technology; and one argues in a straightforward fashion that while investing resources in scientific research may look like a waste, you better do it, because those scientists just might pull your bacon out of the fire when a sudden crisis arises.

More John W. Campbell, Jr. lies somewhere in the future of MPorcius Fiction Log, but the chronoscope isn't providing a clear picture of the whats and the whens right now. Stay tuned.

No comments:

Post a Comment