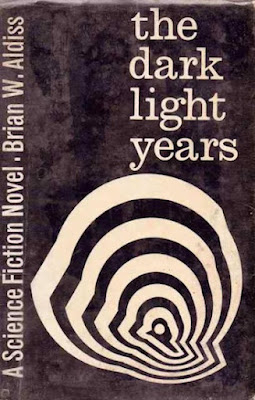

You went because life on Earth was such hell, because, to be quite precise, living with other human beings was such a messy job....Perhaps that was the secret of the exploring spirit. Yes, perhaps that had always been the knowledge in the hearts of the other great explorers! Taxing though the unknown realms were they held no dangers like those that lurked in the breasts of friends and family.Exercising our Reality Privilege back in August of 2021, the wife and I were enjoying the cultural experience of driving across the country when we stopped at an antique mall in Ohio, home state of Edmond Hamilton and Harlan Ellison. At this treasure trove for cheapos I purchased for one dollar Signet D2497, a paperback edition of Englishman Brian Aldiss's novel The Dark Light-Years. A very short version of The Dark Light-Years appeared in the magazine Worlds of Tomorrow in the same year this American paperback of mine and the first edition British hardcover from Faber and Faber were published, 1964. That Faber and Faber hardcover is a good piece of modern design, but my Signet paperback has a pretty damn awesome cover of its own that features a powerful shade of red and a striking image of a human (?) face in some manner of distress.

For a while now I have been exploring with great interest Aldiss's varied body of work, which ranges from stories full of classic SF tropes like a guy who has to fight a dinosaur or who finds himself on a generation ship, to experimental New Wave SF like a "story" that consists of a phrase book of alien words, a body of work that encompasses autobiographical novels about masturbating or serving in Asia in the Second World War, a satire of modern technology set in Africa and a perplexing literary novel about almost nothing. So I am curious to see what The Dark Light-Years is all about.

Despite the horror movie cover on my copy, The Dark Light-Years is written in a tone of understated ironic humor and is a satire of stuff we've already seen satirized many times before. The covers of some later editions showcase a blurb that lauds the book as "sardonic;" if I had seen one of those editions that makes it clear this is a joke story I probably would not have bought it and would not have read it and right now I'd by writing a blog post about "tales of sex and horror" or some Conan or Tarzan pastiche. (Don't worry, those blog posts will be coming up soon.)

In the first chapter of The Dark Light-Years we meet Aylmer Ainson, a Terran living among the fat natives on planet Dapdrof, where the gravity is triple that of Earth's. These three-hundred pound (on Earth, 900 on Dapdrof) natives, the utod, have two heads, six limbs with hands that are retractable like a turtle's head, and eight orifices--one mouth, one anus, six breathing holes; they speak their complex language by using all six orifices. While they have little technology, the utod are a culturally sophisticated space-faring race with a religion whose theology and practice is centered on shit--for example, they consider their own excrement sacred and not only wallow in it but use it in religious rituals, and think of their star's life-giving rays as excrement.

After introducing us to Aylmer we flashback for most of the novel, which takes place forty years earlier. We start with the first meeting of human and utod, an adventure in which Aylmer's father, Bruce Ainson, played a central role. Aldiss also fills us in on the background of the milieu of his novel. In 1999, the Earth was overcrowded, Mars and Mercury had been colonized, Africa was unified under one government, Great Britain was at war with Brazil, and an Australian invented a warp drive that would allow easy travel throughout the galaxy.Around 2035, an utod ship, a thing handcrafted out of wood, has to make an emergency landing on a planet that the crew of a private Earth exploration ship is already investigating. (Aldiss and his characters make a big deal of the distinction between a private commercial space ship and a government space navy ship, the latter very disciplined, the former subject to all kinds of management vs labor strife.) Not realizing the naked mud-wallowing utod are the first intelligent species mankind has encountered after exploring 300 Earth-like planets, the trigger-happy humans blast most of the aliens. They take the corpses and the two surviving ETs back to Earth, to a zoo of alien creatures in London. The peace-like utod don't consider all this a big deal, as war is unknown among them, their biology is such that they feel no pain, and they regard death a blessing, just another of the many changes an utod goes through over the course of its many centuries of life. The utod do, however, ignore all human efforts to communicate.

On Earth, scientists and philosophers argue about the nature of intelligence (could it be there is no such thing as intelligence, that impressive things humans do are just the product of instincts like the instincts that precisely guide migratory birds and marine mammals on trips of thousands of mikes?) and the definition of civilization and try to figure out how to communicate with the aliens. There is plenty of family and relationship drama, like unhappy marriages and parents who don't get on with their kids, and political machinations, one famous scientist or politico or artist doing a favor or refusing to do a favor or publicly humiliating another. Aldiss inflicts upon us readers many scenes of people just talking, blah blah blah, and I am afraid I must say that these relationship struggles are all kinda boring, despite Aldiss's efforts to liven them up by having people dramatically say they need a drink or dramatically smoke cigarettes or dramatically tap their fingers on a table.

Slightly more interesting are the paragraphs of exposition about the dystopian London of 2035, the pollution, the blackouts, the synthetic food (rich people can buy natural foods, but the government discourages the eating of it as unhealthy and lefties worry it is immoral to kill animals and feel it is distasteful to put people--farmers and shippers and the like--to work producing and delivering natural food.) It is not all dystopian, though, at least not on the surface. Characters talk about how there is little crime because "we have recognized crimes as a symptom of sickness or unhappiness...in practice as well as theory...and we don't have prisons, but rehabilitation centers." As for the war between Britain and Brazil, it is wrecking the British economy but the actual fighting is ritualized and highly regulated and confined to Charon, so civilians and infrastructure on Terra are physically safe.Having told us all about Earth, halfway through the shortish novel (which has like 120 pages of text total in my copy) we learn all about the history of the utod. Producing a parody or satire of Earth history, Aldiss describes, in the voice of the utods in the London Zoo, a revolution among the utods over 300,000 years ago. The utods love to wallow in mud and their own excrement, believe in the soul, and have little interest in technology, but a group of innovators developed automobiles, aircraft, electric lights, etc. These revolutionaries also preached cleanliness and denied the validity of traditional utod beliefs, coming up with new moral codes. This revolution lasted only 500 years, collapsing when corruption was alleged among its leaders and fighting, something almost entirely unknown in the utods' millions-year-long history, erupted, and its ideas have never been revived because technology and the new moral codes didn't make the utod people any happier. The exception is that the utod continued to make space ships that are not capable of FTL travel, but allowed then to colonize some nearby systems.

In the final third of the novel the boffins at the zoo in London have made zero progress in communicating with the aloof utod and another vessel is sent out to the region of space in which the utod were discovered in hopes of finding their home world. Aboard this ship, under the assumed name of Samuel Melmoth, is Aylmer Ainson, whose father wanted to be on this expedition but was not recruited because his performance during First Contact with the utod has been deemed inadequate. On this expedition a sensitive woman comes to see the "humanity" of the utod, how they live in harmony with nature ("this was a race without pain...without fear") and she weeps over the fact that Earth people have not been blessed as have these aliens. (Later evidence suggests that, in fact, the utod evolved into pacifists not because they cannot feel pain but because they never had to face any natural predators, and they can quickly become fierce fighters when confronted by enemies.) Meanwhile, the men of the expedition shoot the utod for sport. When the expedition departs, Aylmer Ainson is left behind, the idea being that he will be retrieved in a year or so, during which time he is expected to have learned how to communicate with the utod.The twist ending is that the romantic actions of Aylmer's disgraced father inadvertently and in a circuitous manner trigger a world war on Earth that not only destroys England but spreads throughout space and prevents Aylmer from being rescued from Dapdrof for forty years. It is also suggested somewhat obliquely that contact with humans is going to corrupt the utod and they will become violent like we are.

The Dark Light-Years is merely acceptable. The aliens are sort of interesting (they have little symbiotic companion lizards who clean them of parasites, for example) but the human characters and their relationships are boring. Many of Aldiss's themes and arguments and devices--humans are violent and technological progress doesn't make people happier and look here are some hippy peacenik aliens who live in harmony with nature and dramatize these points--are banal and are not presented in a particularly compelling or fun way.

More interesting is the theme referred to by the title: beyond Earth, in the "dark light-years," where there are fewer rules and fewer people, people can indulge in their base desires, like the killing of animals, and misanthropes can find the solitude they crave. One of Aldiss's characters explicitly equates extrasolar space to "east of Suez" as described in Kipling's "Mandalay," a place where the Ten Commandments do not apply and "the best is like the worst." Aldiss also illustrates the theme of how people are perhaps happier beyond the law and beyond conventional morality when we learn in some brief passages that many of Britain's criminals, almost all men, of course, upon release from custody, take up residence in a walled off section of London known variously as "the Gay Ghetto," "Queer Street" and "Bum's Berg." As the people at Reason magazine and the Cato Institute would have predicted, in this lawless enclave where spontaneous order reigns and there are no taboos about homosexual sex, people are pretty satisfied with their lives.

Hello from Sydney once more. Another insightful post, thankyou. I have a pile of Aldiss novels (all UK editions with great covers) that I bought in the 1970s and have yet to read; one of the added benefits of your blog is that it suggests to me what is worth reading and what is not (my reading time being limited and my library ever-expanding) and this one will move into the charity shop donation pile. Looking forward to more!

ReplyDelete