Greetings, and welcome to another exciting installment of MPorcius Fiction Log. In our last episode I sifted through a pile of old paperback anthologies with awesome covers to read stories by Jack Williamson, and today we read Williamson stories from anthologies which are not quite so old and whose covers are maybe not quite so awesome.

"The Moon Era" (1932)

"The Moon Era" debuted in the same issue of Wonder Stories, edited by Hugo Gernsback, as did Edmond Hamilton's story "Conquest of Two Worlds," which we read a few years ago. I am reading "The Moon Era" in my 1974 hardcover edition of Isaac Asimov's Before the Golden Age, which is so huge (over 900 pages) it was also available as three paperbacks by one publisher and four paperbacks by another. "The Moon Era" is a long story, like 45 pages in Before the Golden Age. It is kind of like a slightly more realistic version of an Edgar Rice Burroughs story in which a guy unexpectedly finds himself in a strange jungle, fights a monster, meets a princess, and fights the princess's war for her. (Part of the realism of "The Moon Ear" is that the guy loses the war and the "princess" gets killed.)Stephen Conway, our narrator, is a school teacher who hates being a school teacher. (More realism!) He is also a pretty healthy bloke--he played football in college!--so his rich uncle recruits him for a special mission: to test fly, to the moon no less, the one-man space ship he just finished building! Just like in the real life 2020s, in this fictional 1930s, it is private enterprise taking the lead in space exploration! Stephen's reward for being the first man in space and the first man on the moon (as if that wasn't reward enough!) is to be made heir to unk's 3.5 million dollar fortune! And unk will start paying Stephen $50,000 a year to tide him over until he dies!

The elder Conway's space vessel isn't propelled by anything so crude as rocket, but instead a technique that renders objects opaque to gravity; you run an electric current of particular specifications through two copper disks, and things between the disks, and the disks themselves, are shielded partly or entirely from gravity. Unk's space ship is a pair of these disks, each like 20 feet across, with a living capsule/cockpit between them--the ship looks like a half empty spool. You steer this thing by varying how much you let sources of gravity affect you. (This is kind of like in H. G. Wells's Cavorite ship in First Men in the Moon.)

When Stephen takes off in this thing an unexpected side effect becomes apparent--the ship is not only shielded from the effects of gravity, but travels back in time. So when Stephen gets to Luna it is millions, maybe billions, of years in the past and the moon has an atmosphere and is covered in jungle!

Williamson describes this jungle in great detail, perhaps too much detail, all the descriptions of different plants not necessarily building up images and a mood so much as a wearisome pile of words. But then an animal attacks and injures Stephen, and it is a pretty cool monster and a good scene, so Williamson is back in our good graces.A native of Luna, a sort of furred telepathic snake-woman, comes along and heals up Stephen with her mental powers. She tells him she is the last of her people; like a queen of ants or bees on Earth, she was mother of an entire tribe, and in fact calls her self "Mother." She relates how long ago the people of the Moon had a technological society with cities and machines. Lunar civilization split into two factions, a back-to-nature faction that realized machines and city life made you weak and abandoned modern life, and a pro-technology faction that kept building more and better machines and atrophied until they were nearly bodiless brains; they installed their gray matter in robot bodies to become what we might call cyborgs. The machine-lovers of today have physically degenerated to the point that they can no longer reproduce, and so tried to kidnap the queens of the snake-people living at one with nature in the jungle, but the queens committed suicide rather than give birth to new members of the cyborg civilization. Mother is the only survivor of the ensuing war, and is on the run. If she can get across the ocean she can start a new in-touch-with-nature civilization with the hundreds of eggs in her eel-like body.

Stephen keeps telling us that Mother, the alien furry snake with doodads like a crest and wing-like membranes sticking out of her vermiform body, is beautiful and there are many instances of her touching him, to facilitate telepathic communication or to heal him or whatever--"The Moon Era," like some kind of proto-New Wave story, is a story of (unconsummated) interspecies love. In the same way in a conventional story the lovestruck narrator might keep talking about a woman's eyes or hair or breasts--their shape and color, the way they move--in "The Moon Era" Stephen talks again and again about this alien's blue crest and the shifting color of her membranes and the muscles moving under the skin of her serpentine body. It is really something.

The interspecies couple is chased for page after page, gets captured, escapes from the city, and in a final battle in which Stephen's Earth muscles give him the power to triumph over his robotic enemies, Mother is mortally wounded. Stephen buries her and gets into the space ship to return to Earth, leaving behind a Luna that will soon be bereft of intelligent life. I guess we are to assume that on the return trip the ship somehow goes forward in time back to the 20th century? Williamson, not wanting to distract from his tragic ending, I suppose, doesn't address this issue.

This story feels kind of long, and I am generally unimpressed by anti-technology stories that advocate pursuing some kind of stone-age lifestyle, but the monsters and the machine people are good and the whole relationship between Stephen and Mother is so remarkable that the story has to be counted a success.

In 1941 "The Moon Era" was reprinted in a British magazine, Tales of Wonder and Super-Science, and it was also selected by Sam Moskowitz for an anthology that appeared in numerous editions under various titles, including Three Stories, A Sense of Wonder, and The Moon Era.

"With Folded Hands..." (1947)

This is a pretty famous story; it was included in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume Two A, and in 2018 the Libertarian Futurist Society recognized it with the Prometheus Hall of Fame Award. It debuted in Astounding and I am reading it in Isaac Asimov Presents The Golden Years of Science Fiction: Fifth Series, which is a 1985 hardcover omnibus edition of the two volumes of Isaac Asimov Presents the Great SF Stories that covered 1947 and 1948.Mr. Underhill lives in a small town in the spacefaring future in which many planets have been colonized by Earth people. When he was young he wanted to be an engineer and build fission power plants, but then he met Aurora, with the beautiful red hair. He married her and then found that he had to take over the robot store ("mechanicals agency") Aurora's drunk and lazy father had been driving into the ground. Now the Underhills have two kids and money troubles because the robot market is saturated and the robots Underhill sells aren't materially superior to all the other firms' robots.

The day the story begins Underhiull gets one piece of distressing news after another. A new robot store, selling "Humanoids," has sprung up out of nowhere. (Much the way the store in A. E. van Vogt's "The Weapon Shop" just suddenly appeared.) The Humanoids, imported from another planet, are so much better than any robot manufactured on Earth Underhill knows his firm is doomed. And Aurora has found a new lodger for the room over the garage. In the past Aurora's lodgers have refused to pay the rent and turned out to have been criminals, and at first this new one, an old man named Sledge, doesn't seem like he's going to be much better.

As the story proceeds it becomes clear that the Humanoids constitute a benevolent dictatorship come to run the lives of everybody on the planet; humans need not work--the Humanoids will do all the work, and do it more safely and efficiently than humans can. The Humanoids do not take no for an answer, but use irresistible sales tactics in pursuit of their mission of securing human safety. Soon everybody is unemployed and every person has a Humanoid minder who drives for him, cooks for him, even opens doors for him and shaves him, because all those activities run a risk of injury when done by mere humans. Obviously people aren't permitted to cook or throw darts or play football or anything dangerous like that, and even reading novels soon falls under the category of the forbidden.The lodger Sledge turns out to be a refugee from the planet on which the Humanoids originated. In fact, this old codger invented the Humanoids and a bunch of other stuff, like the human race's first FTL drive and a wireless energy transmitter and so on, stuff that has made the Humanoids possible. He tells Underhill the long and sad story of his career, how his early inventions led to mass war on his home planet and how he then invented the Humanoids to serve as protectors, as a prophylactic against human violence ("I was determined to build better mechanicals, immune to human imperfections, able to save men from themselves") and how that didn't work out well, either. The Humanoids, massed produced on the inventor's home planet, have been spreading throughout the galaxy, taking over one planet after another--because they have the FTL drive they can outrun warnings about them. Only Sledge in his own FTL vessel can keep ahead of them.

Readers of Williamson's Legion of Space books will recall that the series featured a tiny superweapon that could blow up a whole planet. Well, Sledge, with the help of Underhill, builds a tiny superweapon that can blow up his home planet and thus deprive the Humanoids of their power source and central computer. But our heroes fail--the super-efficient Humanoids have predicted just such an attack and put up the appropriate shield against the super weapon. Sledge is taken by the Humanoids to the hospital and his brain is altered surgically so that he loves the Humanoids' rule; Underhill starts pretending to share that love so as to avoid a similar fate.

We've read quite a few stories here at MPorcius Fiction Log arguing that Utopia is a nightmare and to be happy people need challenge and goals and risks*, and here's another one. It is easy to see why the Libertarian Futurist Society would like "With Folded Hands...," with its theme that too much government intervention into your life is bad, even if it is ostensibly for your own good, and even if the government isn't run by a bloodthirsty monster or a senile goofball, but entities benign and flawless.

It feels kind of long (it's like 45 pages in Isaac Asimov Presents The Golden Years of Science Fiction: Fifth Series) but "With Folded Hands..." is not bad. Readers will perhaps be reminded of Isaac Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics by the Humanoids' "Prime Directive" of "To Serve and Obey, And Guard Men from Harm," and of course the ending is reminiscent of George Orwell's 1984.

"With Folded Hands..." was a big success, and has been printed in many collections and anthologies in many languages, and was followed by a novel-length sequel serialized over three issues of Astounding in 1948 under the title "...And Searching Mind."

*A sample from just 2021 and 2020: Leigh Brackett, "Child of the Sun (1942), Raymond F. Jones, "Rat Race" (1966), Henry Kuttner, "The Land of Time to Come" and "Remember Tomorrow" (both 1941), Ray Bradbury, "Pillar of Fire" (1948).

|

| On the cover of Der Pandora Effekt we can see Sledge and Underhill working on their superweapon |

Behold downer number three! Our protagonist is a little boy from the city; he and his birthing person and her life partner had to leave the city and his friends to move to a farm so remote there isn't even a public school for him to attend, all so Dad could grow marijuana. This kid finds a strange plant and feels a strong attachment to it. Dad thinks it's the kind of weed he doesn't want to cultivate and goes to pull it out of the ground, but the kid protects the plant and cares for it, watering it when it doesn't rain, for example.

The plant grows into a little tree with lovely flowers. The kid dreams that at night he goes to the tree and talks to little flying people he calls "fireflies," who tell him his beloved tree is from space and out there is a galactic federation of thousands of peaceful intelligent species who all get along; these happy people sent the tree to Earth to invite the human race to join their peaceful civilization.

When the kid tells his parents this stuff they fear he is mentally ill and Mom takes him to the doctor. When the kid and Mom get back from the doctor's office they find the police have put Dad in their squad car and are in the process of burning the marijuana...and in a case of mistaken identity as tragic as the one in The Rolling Stones' "Doo Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker)" the tree from space is also being burnt up! Mom and the kid go back to the city, but the kid is not interested in hooking up with his old friends, he just grieves for the fireflies, his father, and "all that might have been."

This is well written, but it is a sappy story, and feels like something written for children. Merely acceptable.

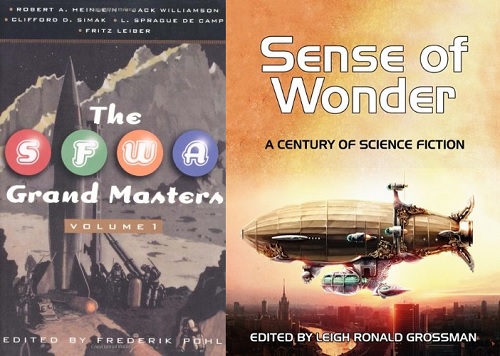

I am lukewarm about it, but the SF community seems to have embraced "The Firefly Tree." Fred Pohl included it in The SFWA Grand Masters Volume 1 and it also appeared in a 1000-page textbook on 20th-century SF edited by Leigh Ronald Grossman.

**********

I didn't expect all these stories to be tragedies in which intelligent life on a planet goes extinct, or mankind loses any semblance of freedom, or a kid is scarred for life by a glimpse at limitless possibilities which are snatched away. But I like to be surprised, and it is certainly nice to know a guy can write viable entertaining stories across a period of seven decades!

More from my collection of paperback anthologies in our next episode!

Hi. I enjoyed reading your account of, "The Moon Era". That story has meant a lot to me ever since I read it in a, "Before the Golden Age" anthology by Isaac Asimov. So it is good to read an account of it by someone else.

ReplyDeleteI must admit the end really upset me! I would like to have asked Jack Williamson why he killed off the Mother! I did find that really sad. Firstly the Mother (who seemed like a very nice being) getting killed and secondly that with her dying the moon would be then bereft of benevolent, intelligent life. Especially with the sacrifices that the rest of her people had made in helping her to escape. Basically they had died in vein. Extinction is a terrible thing, especially extinction of benevolent, intelligent life. I even found the idea of the Immortals dying out a bit sad. At the end of the day they were only trying to survive Why do you think Jack Williamson killed the Mother off? Was he trying to be realistic?

I think lots of literature is tragic--The Iliad, King Arthur, Beowulf, Proust, etc.,--they are all about loss, sacrifice, defeat, people doing the wrong thing and regretting it, people trying to do the right thing and failing, the world changing in ways the characters do not find comfortable, etc. John W. Campbell, Jr. thought science fiction should be a literature of optimism that celebrated man's ability to overcome obstacles and improve his life by learning about the universe and mastering it, but many SF writers still work in the tragic vein, for example warning of possible drawbacks of science and technology. There is also a tradition of adventure stories like Burroughs's Barsoom books being set amid the ruins of a lost civilization or in the last days of a dying civilization--the work in Weird Tales of Robert E. Howard, H. P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith is full of lost civilizations and civilizations in decline.

DeleteOn a more practical note, the moon in our day is a dead world, and when Williamson thought about depicting a moon of long ago full of life, maybe it was just logical to speculate on how that vibrant world became the inert rock of today.

Hi. Thank you for your reply. I have wanted to get off my chest what I thought about the Moon Era for a long time. In some ways your reply does make me feel a bit better!

ReplyDeleteIt is very true what you say. I like ancient Greek mythology and although it is a good story, I do find the finale of Troy distressing, how a rich, vibrant civilization is wiped out overnight in an orgy of atrocities, largely motivated by greed. Although some of the Trojan refugees do go on to found new civilizations and some of the captive Trojan women go on to have descendants. Whereas on the Moon Era, that is the end, full stop. I think that is what I find so upsetting! I do think though that no matter how far the Mother went, the Eternal Ones were not going to give up. I think that the only way that she might have got away is if the main character gave her a lift in his spacecraft (which he sort of offers). The only other way that her race might have lived on is if he had found a way of extracting her eggs from her dead body and somehow animating them. Although I could understand that he would be loathe to do this (it does smack of desecration) even if it had have been possible. It does make you wonder why the Mothers could not have given the Eternal Ones some eggs to help them survive, if that is all that they wanted to do, on the condition that the Eternal Ones left them alone. In that way both races could have lived on, at least until the moon became uninhabitable. I wonder what it is that the Mother tried to say to the main character after she got fatally clobbered? That was a bit annoying not knowing that!

I think though that it is the sign of a good story if it does elicit a strong reaction from you, whether it is happy or sad. This definitely falls into the sad category. I do often find that tragedies probably do have a stronger and longer lasting effect. A film which brough out a similar emotion was, "Waterloo Bridge", the 1940 version. It is a war drama, rather than sci-fi.

At the end of the day though, they are fiction. I think that the moral of the story is that if you see any tragedies in real life, then you try and help them stop happening, if possible.

I do like old science fiction (I can understand it better than a lot of modern science fiction!) so I will probably read your other entries. I do recognise some of them as stories which I read a long time ago.

Cheers.