Even though this book is called The Year's Best Horror Stories, the publication dates of the stories in it range from 1971 to 1973. This American book is, it appears, a selection of stories from two British anthologies edited by Davis, 1972's The Year's Best Horror Stories No. 2 and 1973's The Year's Best Horror Stories No. 3. This makes me wonder if Lee's foreword is literally about the eleven stories here in this book, or if it is just a reprint of his foreword to The Year's Best Horror Stories No. 2.

(A detailed bibliographic article by Todd Mason about the DAW Year's Best Horror anthologies at his blog was helpful to me in solving the mysteries of this volume.)

We'll start with four stories, two by Brian Lumley and two by Ramsey Campbell. I have had mixed feelings about these gentlemen's work, so there is a significant chance I will have to disagree with Lee about these tales.

"David's Worm" by Brian Lumley (1971)

"David's Worm" first appeared in a magazine called Pulp in 1971, a magazine I am not having any luck finding info about online. It has been reprinted in several places, including in the British collection The Second Wish and Other Exhalations.

I actually recognized this story almost at once; I must have read it in the US collection Beneath the Moors and Darker Places when I borrowed if from the New York Public Library over ten years ago. It is an acceptable horror story based on the now exploded belief that planarians who eat other planarians gain the knowledge of the worms they have devoured. The style is sort of oddly folksy, perhaps an effort to simulate the way a vocal storyteller might relate the story face to face in a bar or around a campfire or something.

A "radio-biologist" is showing his seven-year-old kid slides of small living things, amoebas and diatoms and so on, that have been irradiated to death. The kid thinks he sees a planarian on a slide move, so he steals the slide and puts it in a pond. The worm is revived, and begins eating everything in the pond and growing to tremendous size (for a planarian.) It takes on the personality and attributes of those it digests, including a dog and an aggressive pike, and eventually eats the seven-year-old. The monster invades the scientist's house and tries to eat the kid's parents--the quick thinking boffin destroys the creature, but not before it chillingly speaks in his child's voice.

This story always reminds me of the alzabo from Gene Wolfe's Book of the New Sun.

"Haggopian" by Brian Lumley (1973)

"Haggopian" first appeared in F&SF (read it for free at the internet archive, cheapos!), and would later be the title story of a Lumley collection. This is a Lovecraftian piece, with an elaborate frame in which the narrator is a journalist who secures an interview with the titular Richard Haggopian, famous but reclusive ichthyologist of mixed race (Armenian and Polynesian, among other ethnicities), on his tiny private island near Greece. Haggopian has a weird sheen to his skin, wears dark glasses indoors and out, and walks oddly.

The scientist tells the journo the story of his career, how he travelled around the world, finding evidence of Cthulhu and Dagon and other ancient aliens and gods on sea coasts from New England to Polynesia to Africa. To be honest, all these direct references to Lovecraft stories do not add to Lumley's story; they just make it longer. Haggopian's story could be told without any reference to Innsmouth or any of that stuff.

The significant portion of Haggopian's tale is that one day he caught an intelligent hagfish, a slimy eel-like four-foot long parasite, of a previously undiscovered species. This creature, like a vampire, has hypnotic abilities it uses to seduce its victims; said victims not only submit to its biting and drinking of their blood, but actually derive (sexual?) pleasure from giving their life force to the hideous fish! In the same way that a vampire can turn its victims into vampires, the hagfish has altered Haggopian's physical makeup, so that he can now breathe underwater and has an additional organ (not unlike a second penis, frankly) that can latch on to other living things and suck their juices. This interview with the narrator will be Haggopian's last--he is almost fully transformed into a fishman, and will soon abandon the human race and the surface world and join the hagfish monsters' subterranean community. It is strongly suggested that Haggopian has been sucking the blood of his current wife (a Greek fashion model--vampires always get the best chicks!) and that she will soon become a fishperson herself and join him in the briny deep, and that his first wife is already down there awaiting him.

This story isn't bad, if we ignore the superfluous direct references to Lovecraft stories and characters. Writers who would emulate Lovecraft should expend their energy achieving the Providence weirdo's tone and mood and so forth, not just throw catchphrases and words famously used by Lovecraft into any old story in a cheap attempt to get us Mythos fans on their side.

"Napier Court" by Ramsey Campbell (1971)

Alma is a young Englishwoman who works at a museum and plays the flute; she lives with her parents in a big Victorian house called Napier Court. She has a cold, and is looking forward to spending two weeks in bed resting while her nagging, smothering parents are away on holiday--she has plans to read Eugene Ionesco's Victims of Duty in the original French, which wikipedia is leading me to believe is an absurdist play drawing on Ionescu's difficult relationships with and mixed feelings about his parents and the theater.

Alma's ex-fiancee Peter, recently dropped at the insistence of her parents, and her friend Maureen, are god-damned commies, who tell her that her love of music and the finer things is just a way for her to hide from the suffering of the local poor and the people of Hiroshima and all the other victims of the bourgeoise.

"Why must you and Peter always look for the horrid things? What about this house? There are beautiful things here. That gramophone--you can look at it and imagine all the craftsmanship it took. Doesn't that seem to you fulfilling?"

"You know we leftists have a functional aesthetic."This chick Alma is surrounded by downers!

Anyway, from the local gossip mongers and from Maureen, Alma has gotten the idea that her house full of beautiful things is haunted; the previous owner is said to have committed suicide after losing his money in the stock market. Shortly before his death he complained of a mysterious inhabitant of Napier Court, and in his suicide note he wrote of "fading into the house."

Alone in the house, weighted down with regrets that Peter is gone but also obsessively recalling all the times he contemptuously derided her music and badgered her with his political convictions, Alma either goes insane (maybe in part because of some medicine she takes) or the house comes to life and absorbs her. It also seems possible that she masturbates with the flute. It's all a little vague and confusing.

The repeated references to Ionesco, Vietnam, and sexual relationships suggest that this story demands some kind of ideological analysis. What could the story's ideology be, and what critical theoretical lens should we employ to analyze it, fellow students?

Marxist/class analysis: Alma, like the rich dude who owned Napier Court before her parents, cares more about property than the suffering poor and the non-white victims of what I call the Pacific War and the struggle against communism and my college professors called America's imperialistic pursuit of markets. (Alma not only expresses affection for the house and her flute and her records, but doesn't give back Peter's ring when she reluctantly breaks off their engagement.) Social justice is served when she becomes one with the house, essentially choosing to marry and have sex with property instead of Peter. This analysis is buttressed by the way Alma's mother decries Alma's relationship with Peter, whom Mom says "is beneath her."

Freudian/pro-sex analysis: Alma has normal healthy sexual desires, but her stuffy bourgeois upbringing and her parents, who police her every move, keep her from fulfilling them with Peter. Alma's mother isn't sexually attracted to or fulfilled by her husband (they sleep in separate rooms), and Mom takes out her frustrations by obstructing Alma's relationship with Peter, of which she is envious (Mom at one point remarked that Peter was "a handsome bugger.") Alma resolves her desires by having sex with the flute and the ghost, whom she "marries" when she becomes one with the house.

Feminist/individualist analysis: Alma is a creative and sensitive soul with her own ideas of how to live her life, but our patriarchal society crushes her! Peter and the ghost of the previous house owner treat her as a sex object, always trying to get into her pants whether or not she affirmatively consents. Peter, ostensibly an ally because he is always blithering about the poor and non-whites, in fact is an oppressor, psychologically dominating Alma--he tells her what to think, mansplains why her hopes and dreams are stupid, and renders her psychologically dependent on him. (He does to her all the things those "game" theorists say you should do to get girls.) Mom, herself the victim of the patriarchal institution of marriage, sees that her daughter is in trouble, but, her psyche colonized by Victorian bourgeois nonsense about heterosexual love (Mom has a collection of 19th-century Valentines Day cards), is incapable of modeling a strong independent woman for Alma, and just nags her daughter, stifling poor Alma and sabotaging Alma's efforts to achieve independence. In the end Alma is wholly absorbed by the male/collective entity of the house, like a subservient, oppressed wife.

Good work, class! Next stop, grad school! (Destination: Starbucks!)

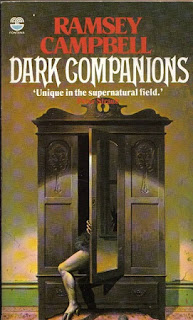

"Napier Court" isn't bad, but it feels kind of long and tedious; individual scenes are crowded with too much detail, and all the descriptions of figures and shapes behind Alma or in the corner or wherever get repetitive. "Napier Court" first appeared in August Derleth's Dark Things and would be included in the Campbell collection Dark Companions and an oft-reprinted anthology of stories about haunted houses.

"The Old Horns" by Ramsey Campbell (1973)

This is a muddled mess of a story, difficult to get a handle on, and unable to excite enough interest to make the challenge of figuring it out worthwhile.

A bunch of people go on a picnic to the beach. Near the beach is dangerous soft ground amid some fungus covered pine trees; the characters liken it to quicksand. This danger zone is called "The Old Horns." Our narrator is an introverted poet who tries to compose a poem but is distracted by his companions. One member of the group is a boorish guy, George, who is always trying to flirt or get his hands on the women. George talks about pagans, celebrating their open attitude towards sex, and the narrator tries to correct him, saying that paganism was degrading, dehumanizing. The poet uses the word "rot" to describe the effect on the human soul of paganism, and describes the Old Horns as being full of rotten wood on the next page, connecting the place and paganism.

The picnickers play hide and seek. Our narrator, while hiding, witnesses some kind of strange dancing parade of people in strange outfits and over-sized masks, a sort of pagan ritual--this vision turns out to be just a dream. He returns to the group, but George is missing. Everybody figures George made his way home to watch Julie Christie on TV (Campbell loves to mention literary and pop culture figures in these stories--in "Napier Court" he mentioned Michael Caine.) But the narrator suspects George is trapped in the quicksand or something, and when everybody goes to a restaurant, our hero heads back to the beach to look for George. He sees George in the darkness, in a reflection in a pool. George is moving jerkily (perhaps foreshadowed by the robotic gait of a child's clockwork doll in an earlier scene as well as the narrator's dream) and appears to be headless, the moon visible between his shoulders.

What am I supposed to get from this story? If you abandon yourself to sexual license you will lose your soul? Does the title refer to the Devil? Our culture has been so sympathetic to paganism and promiscuous sex for so long that a story taking a contrary view is a good idea, but this story just isn't all that good. "The Old Horns" is just too vague and too confusing, feeling flat and inspiring no emotion. Thumbs down!

"The Old Horns" first appeared in the collection Demons by Daylight.

**********

Today's Lumley stories, which are just trying to be icky and fun, are too simple and obvious, and the Campbell stories, which aspire to literary and philosophical significance, are too confusing and vague. Maybe the writers in the next installment of our look at DAW No. 109 will be better able to achieve a happy medium?

**********

The back cover of DAW No. 109 tries to piggyback on the success of the 1973 film The Exorcist, which I saw in a special rerelease ("Version You've Never Seen/Extended Director's Cut") in a crowded Manhattan cinema with my wife in 2000. I'm a queasy sort, and the elaborate medical scenes near the beginning of this version of the picture brought me close to fainting. The famous possession scenes didn't have any effect on me, partly because the audience laughed all through them. (Audiences similarly impeded my enjoyment of 2000's Uzumaki, which I saw in a little theatre in the Village during my brief Japanophile phase when I would hang around Jim Hanley's Universe in the shadow of the Empire State Building reading entire volumes of Maison Ikkoku and at a midtown Japanese bookstore marveling at the insane work of photographer Nobuyoshi Araki and draughtsman Toshio Saeki.)

Remember when we caught DAW trying to capitalize on the popularity of Star Wars?

The back cover also advertises A. E. van Vogt's The Man With A Thousand Names, which we read during our 2016 van Vogt Marathon.

Doing three analysis of a Ramsey Campbell is heroic blogger work!

ReplyDeleteI'm afraid I've mostly bounced off the little Campbell I've read usually finding him too oblique and too long.

Thanks! I'm there in the trenches, hacking away!

DeleteOne of the benefits of maintaining the blog is that it encourages me to read carefully and to consider what I have read, rather than just abandoning things that don't immediately click, to find interesting things in stories I don't particularly like, if only a deeper understanding of why I don't like them.

Cover by Hans Arnold (1925-2010). Born in Switzerland, lived and worked most of his life in Sweden. Many SF-books in Sweden has cover artworks by Arnold. His works can also be found in SF-magazines as Häpna! among others. /Mats Paulsson

ReplyDeleteCool! DAW No. 109 was a real international effort!

DeleteHäpna! was our first real SF-magazine in Sweden, and existed between 1954 and 1966. ("Häpna!" = "Get Stunned!")/Mats

DeleteI really enjoyed this DAW series. What do you think of today's "YEAR'S BEST" horror anthologies?

ReplyDeleteAlma: This one time at band camp..

ReplyDelete