"The Moon That Vanished" (1948)

The fourth story in The Best of Leigh Brackett is "The Moon That Vanished," which I read back in 2014. Looking back at my blog entry about the story, I see I detected in it the same theme of the superiority of real life and real sexual relationships to masturbatory fantasies that I recently noted in "The Jewel of Bas." I also thought it better than Brackett's "Terror Out of Space" and "Citadel of Lost Ships"--I guess Hamilton did, too, because those stories aren't in this collection.

"Enchantress of Venus" (1949)

This is, I believe, the second of Brackett's Eric John Stark stories. Stark is a Burroughs-style hero, an Earthman orphaned as a child on Mercury and raised by Mercurian savages. His time on Mercury gave him superhuman reflexes and senses, as well as very dark skin, thanks to the proximity to the Sun.

This story begins with Stark on Venus, passenger on a boat floating on a sea of red heavier-than-air phosphorescent gas, bound for Shuruun, a town of pirates and drug dealers. He narrowly escapes being kidnapped by the boat's treacherous crew, but before long ends up in the hands of the decadent aristocrats who rule Shuruun, the Lhari clan, anyway. The Lhari are a disgusting dysfunctional family, their matriarch a woman so obese she can barely move, her children and grandchildren and their spouses a pack of cripples and backstabbers always at each other's throats. (There's a lot of relationship violence and domestic violence in this story--the boat captain who initially tried to kidnap Stark beats his teen-aged daughter, for example, and when Stark and a woman kiss Brackett describes their embraces and caresses as "rough and cruel," Stark holding her "as though she were a doll.") The Lhari put Stark to work on their slave gang, excavating the ancient ruins of the austere ebon city that lies at the bottom of the red gas sea, but Stark is so sexy that one of the Lhari, a beautiful silver-haired young woman named Varra, whom Stark thinks of as a "bold as brass" "hellcat" with a "swagger" which "at once irritated and delighted" him, tries to seduce him. If Stark can kill off the rest of her family Varra will marry him, making him co-ruler of Shuruun and founder of a new, virile, dynasty.

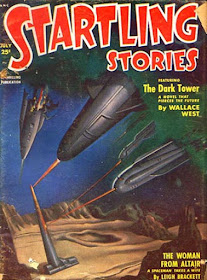

|

| That must be Varra, who sics her flying monster on her fiance and other people who inspire her anger |

Brackett's story is also characterized by brutality. I've mentioned the rough sex and violence between family members, and will add that Stark, who lived practically as an animal on Mercury, fights like an animal--more than once in hand-to-hand combat he bites an enemy bloody. Yuck! (In a story in which there are so many sexual overtones, you have to wonder if Stark biting other men has some kind of homoerotic charge.)

Anyway, Stark, with the help of a renegade member of the Lhari clan, a cripple who prophesized Stark's coming and has discovered via cleverness the ancient technology his family is searching for via slave labor, leads a slave rebellion and in the fighting the Lhari are wiped out.

A very good story--I have talked a lot about "Enchantress of Venus"'s atmosphere and mood, but Brackett also does a good job with the characters--the 70-page story features more than I have mentioned here--with even minor characters like the boat captain and his daughter having memorable personalities and following "arcs"--with the fight scenes, and with the pacing and style. Anybody who likes John Carter or Conan or Elric should like this one, and I'm sure the story is ripe for some kind of feminist analysis, an examination of whether and how a woman works with this sort of material in a different way from a man. "Enchantress of Venus," first appearing as a Planet Stories cover story, has apparently already been the subject of scholarly attention, being included in 1978's Approaches to Science Fiction and 2000's The Prentice Hall Anthology of Science Fiction and Fantasy, as well as a bunch of other Brackett collections and SF anthologies.

"The Woman from Altair" (1951)

The narrator of "The Woman from Altair" is Rafe McQuarrie, scion of the wealthy McQuarrie clan, a family made rich these last two centuries via interplanetary trade and exploration. Injured in an accident, Rafe has been unable to live the life of a space explorer (instead he's been working as chief financial officer of the family business), and so when interstellar travel was recently developed it was Rafe's little brother David who became a world famous hero by exploring other star systems and bringing back alien valuables. As the story opens, David returns from an interstellar trip to uncharted worlds, and the assembled McQuarrie family and a gaggle of officials and journalists are amazed to lay eyes on one of these valuables--a gorgeous purple-haired and purple-eyed alien woman named Ahrian! Perhaps most surprised when David announces that this alien is his wife is David's human fiance!

The first part of "The Woman from Altair" gave me a Heinlein vibe, reminding me in particular of 1957's "The Menace from Earth." There's the clever and smart-alecky characters with their witty comments and a plot about flirtations and courtships over a background of speculations about what life will be like in a spacefaring future. But Brackett's story, while doing that stuff, takes a very dark turn, with horror and mystery elements that took me by surprise when they first reared their ugly heads, and an ending that questions the very wisdom of exploring outer space!

Rafe's little sister Bet, and other women, are skeptical of, even hostile to, Ahrian, but that can be dismissed as envy over Ahrian's good looks and sympathy for David's jilted fiance, can't it? But when the family dog and Bet's favorite horse attack and kill (!) Bet, we readers begin to suspect something is not right with this sexy space lady! Then Rafe stops calling his girlfriend Marthe, an aggressive news reporter, and having disturbing dreams of Ahrian's planet and obsessive thoughts of suicide! Marthe storms over to the McQuarrie estate and tells Rafe that women sometimes get "nearer the truth than men because we aren't ashamed to rely on the instincts God gave us." And what is Marthe's women's intuition telling her about Ahrian? "She's evil. She's filled the house with death."

Marthe, using her journalist skills and energized by her love for Rafe, figures out what is going on and puts an end to Ahrian's telepathic reign of terror over the McQuarrie family.

This is a good story; the characters are well-drawn, the plot and pacing work smoothly and can surprise the reader. Beyond being entertaining, "The Woman from Altair" is interesting in all sorts of ways. Like "Enchantress of Venus," it is the story of an outsider disrupting a powerful and wealthy family, but in this one the family is, more or less, the "good guys" and the outsider the villain. I say "more or less" because Brackett isn't reluctant to show us the stresses of family life and doesn't absolve the McQuarries of responsibility for their tragedies. Rafe was expected to be another in a long line of McQuarrie space heroes, but he wasn't interested in leaving Earth and his beloved dogs and horses. When he did reluctantly go up on a trip to Mars he developed a debilitating fear of space, so he deliberately caused that accident which grounded him in order to get out of space duty! Even worse, Ahrian didn't seduce David on Altair in order to get to Earth to murder people--sleuthing Marthe learns that Ahrian's family needed some Earth drugs, and David pressured the girl with the amethyst locks into marrying him in return for the medicine, practically buying her! Ahrian is using her mind powers to murder McQuarries to get revenge! (Cleverly but unobtrusively, Brackett presents Ahrian and Rafe to us as parallels--each loved her or his planet and didn't want to leave it, but had to leave to satisfy filial duty!)

Perhaps I should note that the hero of the story, pushy reporter Marthe, is almost as much an outsider as the villain--in her efforts to get a scoop she injects herself into the McQuarrie milieu the same day Ahrain arrives, only later falling in love with Rafe.

Though Ahrian is killed, the stress of her campaign of vengeance, which killed Bet and drove David and Rafe to the edge of insanity, leaves terrible scars on the McQuarries: they abandon their 200-year-old estate and David's career as a space captain is over. The final lines of the story have Rafe asking why mankind goes to the stars at all: "Have men ever brought more happiness back from the stars? Will they ever?" Again we see Brackett repudiating the forward-looking sense of wonder we so often associate with SF (as well as flouting conventional economic theory by suggesting trade is a waste!)

The leading role of women in the story is of course noteworthy; our narrator may be a man, but the hero (Marthe), the killer (Ahrian) and the murder victim (Bet) are all women. Appropriately enough, Pamela Sargent included "The Woman from Altair" in her 1995 anthology Women of Wonder: The Classic Years. I wonder if in her intro or notes Sargent remarked upon the traditional notions about women Brackett fills her story with, like women's intuition, women as manipulators of men, and women jealously competing with each other over men. Brackett seems to have had essentially conservative politics; Alpha Centauri or Die!, which I read in 2014, has an anti-big government message and a traditional view of gender roles, and in his essay "Queen of the Martian Mysteries," Michael Moorcock says that Brackett's politics were closer to those of John Wayne, with whom she worked in Hollywood, than Moorcock's own. Of course, Brackett cleverly presents us with a male first-person narrator, casting some ambiguity over every comment he makes about women (and about the wisdom of space travel, for that matter): is Rafe always expressing Brackett's own beliefs, or is Rafe merely a product of Brackett's speculation of what a man's interior life might be like?

"The Woman from Altair" first appeared in Startling Stories. In 1965 it was reprinted in a magazine called Treasury of Great Science Fiction Stories along with pieces by other important SF authors.

**********

Two really good stories, fun and thought-provoking, embracing genre traditions but taking them in unusual directions and mixing them up a bit. Recommended to all genre fiction fans and students of pop culture created by women and depictions of women in pop culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment