"The Man of Stone" (1932)

This story takes place in the Adirondacks of upstate New York, in the environs of Lake Placid. Some of my ancestors on my mother's side lived in Lake Placid, and my mother has all kinds of sentimental and romantic feelings for the Adirondacks and the people who live there, and we took many vacations to Lake Placid in my youth. My favorite Lake Placid memory is how, driving up one year (I guess now you can take a superhighway straight up to Lake Placid, but when we went in the '80s you took twisty windy one-lane roads), my brother and I made pistols out of Legos and used them to defend our family station wagon from all the tractor trailers we saw, which we pretended were monsters we called "Cujos"--we had heard vague references to the Stephen King movie, but had no idea it was about a dog, and to our childish minds "Cujo" had a beautifully brutal and sinister ring to it.

Back to "The Man of Stone." The narrator and his best friend haven't seen their pal Arthur Wheeler, sculptor, in a while; he went up to the Adirondacks to do some sculpting. (Uh oh, remember when that dude in Henry Kuttner's "The Frog" left NYC for the country to paint?) A fourth member of their circle staying in the woods as a rest cure returns to civilization and says he saw some strange, uncannily realistic statues in the woods--could these be Wheeler's work? The narrator and his best bud high tail it upstate to investigate.

They find in a cave the petrified body of Wheeler, and in the shack he was renting a similarly petrified old man and a younger woman. And a diary which explains all. (These Lovecraftian stories often include old manuscripts and diaries and so forth.)

The diary, written by "Mad Dan" Morris, makes up over half the 14-page story. Dan was descended from a clan of people who worship alien gods like Shub-Niggurath and Tsathoggua and whose preferred reading material is classics like The Book of Eibon. He used hypnotism to marry pretty young Rose, and physical violence to keep her. A jealous guy, soon after renting out space in his cabin to Wheeler he suspected that Rose and Wheeler were having an affair, so he plotted to murder them. (Rose wasn't much of a wife anyway, due to religious differences--she refused to attend the rituals and sacrifices to his family's gods, for example. Mixed marriages can be tough.) He thought a poetically appropriate way to kill them would be to turn them to stone with a spell he found on a sheet of paper stuck in his copy of The Book of Eibon. (In keeping with Lovecraft's materialism, the spell isn't magic per se but rather super science.) Dan managed to get poor Wheeler, but Rose was a tougher nut to crack, and, in fact, she turned the tables on him, forcing him to drink the petrifying poison before drinking it herself to commit suicide. Right before she killed herself she wrote a postscript to Mad Dan's diary, detailing her escape and her and her wizardly husband's final stony fates.

This is a decent story. It is kind of fun to read a Cthulhu mythos story from the point of view of the self-confident worshiper of the ancient alien monster gods instead of just from the point of view of a horrified researcher or somebody like that. And maybe my mother would appreciate that Lovecraft and/or Heald considered the scenery of the Adirondacks to be "breathlessly exquisite."

"Man of Stone" first appeared in Wonder Stories, and, a reflection of the fact that a woman plays a prominent role in the narrative and that a woman had a hand in writing it, was also included in the 1994 anthology New Eves: Science Fiction About the Extraordinary Women of Today and Tomorrow.

"The Horror in the Museum" (1932)

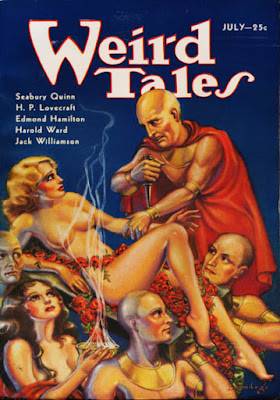

The title story of this collection appeared first in Weird Tales, in the same issue with Lovecraft's "Dreams in the Witch House."

This time we get a third-person narrative set in a decrepit section of London full of decaying homes and warehouses. Jones becomes a regular visitor of Rogers' Museum, an establishment in a dark basement full of wax figures of vicious criminals and their mangled victims--Rogers once worked at Madame Tussaud's. But Rogers' Museum includes uniquely bizarre alien creatures, and when Jones becomes friendly with Rogers, the worker in wax claims that his strangest exhibits are preserved specimens of once-living things, not artificial figures at all!

Jones scoffs, and Rogers tells him increasingly incredible tales of his trips to strange corners of the world with his odd foreign-looking and foreign-sounding assistant, Orabona, trips upon which they collected the Museum's weirdest and most horrifying exhibits.

As he tells it, Rogers' strangest and most important journey was to the three-million-year-old ruins of an alien city in Alaska, where he and Orabona retrieved from its ancient throne a monstrous god, Rhan-Tegoth, a being not dead, but dormant. Rhan-Tegoth, which lies behind a locked door, is a bone of contention between Rogers and Orabona--Rogers wants to revive the monster (via bloody sacrifices, of course) while Orabona wants to destroy it; a revived Rhan-Tegoth could very well take over the world or trigger the cataclysmic return of "the Old Ones."

|

| If I had the jacket to my copy, it would look like this. |

I love the plot, and that the characters are all participants in the drama, not just placeholders in a frame story who find a manuscript which tells us the actual story. I actually wasn't sure what was going to happen in the end, and I actually cared what was going to happen. Lovecraft and/or Heald do a terrific job of describing the characters, the settings and the monsters, and the narrative moves at just the right pace.

Very good: five-and-a-half out of six long sinuous limbs terminating in black crab-like claws!

"Winged Death" (1934)

A horror story about academic jealousy with an unreliable narrator? Genius!

Thomas Slauenwite, M. D. was born in my home state of New Jersey to South African parents, and studied medicine at Columbia U and then researched fevers in Africa. He convinced his buddy, Henry Moore, Ph.D., an entomologist, to come to Africa to research the local insects, thus (Slauenwite claims in his journal, recovered by police) making Moore's career. And how does Moore repay his generosity? Well, when Slauenwite becomes famous in the medical field for figuring out how some fever is transmitted, Moore points out to the world that Slauenwite was just lifting his career-making theory from the unpublished papers of recently deceased Sir Norman Sloane, papers Slauenwite found in a house he was renting. Slauenwite, in his journal, pledges to achieve revenge on Moore!

Eighteen of this story's 22 pages are occupied by Slauenwite's journal, which means we don't have to deal with extraneous characters and their peregrinations as we sometimes do in Lovecraftian stories. Slauenwite, besides having a name that is hard for me to spell, is a fun narrator because he is such a self-important jerk, and because he is single-minded in his pursuit of vengeance:

Poisonous snakes and insects everywhere, and niggers with diseases nobody ever heard of outside medical college. But my work is not hard, and I have always had plenty of time to plan things to do to Henry Moore.(Yes, like "Medusa's Coil," this is a story featuring a character who uses the "n-word" with abandon.)

The journal describes in detail Slauenwite's quest for vengeance over the course of the period 1929-32. He treats a crocodile hunter of the Galla people who has been bitten by a "devil-fly"; the local people connect these flies to some ancient ruins they scrupulously avoid because they are associated with the "evil gods Tsadogwa and Clulu." Uh oh! With the croc hunter's help, Slauenwite captures some of the devil-flies, planning to mail them to Moore back in New York in hopes they will bite him and kill him! To prevent Moore, an authority on African insects, from recognizing the flies, Slauenwite crossbreeds them with other species so they look different, and then tests them on his black employees to make sure they are still deadly!

The plan works! Moore suffers a long lingering illness and eventual death, but then come the weird complications. As the Africans told a dismissive Slauenwite, when a devil-fly kills you your consciousness enters the fly's body! The fly that killed Moore, now inhabited by Moore's soul, begins terrorizing Slauenwite, doing such things as landing in his ink pot and then writing cryptic messages on his ceiling! Can Slauenwite swat the fly before it bites him--and if it does bite him, will his soul migrate into the fly?

A great horror story that will remind readers of the fine film The Fly with Vincent Price, and of such acts of biological warfare as the British efforts to infect Native Americans with small pox at Fort Pitt in 1763 and unethical medical experiments like the Tuskegee syphilis experiments conducted by the US government on African-Americans from 1932 to 1972. "Winged Death" first appeared in the same issue of Weird Tales as Edmond Hamilton's fun "Thundering Worlds," and in 1944 was included in the collection Marginalia.

"Out of the Aeons" (1935)

We all know how terrible religious strife can be. It is terrible in the 21st century Middle East, it was terrible in 17th century Europe, and it was terrible on the now-sunken continent of Mu in the 1732nd century B.C. (that's B. C. E. to all you kids). As we read in the expurgated 1909 edition of von Junzt's Nameless Cults, the people of the kingdom of K'naa lived in fear of the god Ghatanothoa, who resided in a fortress at the top of a mountain that looked down on the kingdom. Any human who lay eyes on Ghatanothoa would be turned to stone, but his brain preserved to suffer eternal torment, so when the priests of Ghatanothoa tell the people of K'naa they have to sacrifice 24 young people to Ghatanothoa every year or he'll "ooze" out of his fort and petrify everybody and his grandmother, they hop to it!

But there is one man willing to be the Martin Luther of the year 173,148 B.C. (better known to the people of Mu as the Year of the Red Moon.) That man is T'yog, High-Priest of Shub-Niggurath! He devises a magic scroll that will protect the bearer from Ghatanothoa's petrifying power, and figures he'll climb the mountain, invade the fortress, find Ghatanothoa, and then use his mad Art of the Deal skills on Ghatanothoa, and maybe get that 24 young healthy young people negotiated down to a more comfortable level. Like maybe a dozen armadillos or something. T'yog expects that liberating his people from the oozing menace will win lots of converts to the temple of Shub-Niggurath and maybe even lead to T'yog being declared the new king!

The people of K'naa are totally into this K'naa First policy, well, except for the priests of Ghatanothoa. The priests of Ghatanothoa get one of their best Russian hackers, I mean sneak thieves, to creep into T'yog's quarters the night before the big climb, open the scroll case and replace the powerful spell scroll with a useless fake. The next day T'yog climbs up the mountain, never to return, and the power of the priests of Ghatanothoa is preserved.

The above adventure story appears in the middle of "Out of the Aeons," which was first published as "Out of the Eons" in Weird Tales. The beginning of "Out of the Aeons" covers how in the 19th century a Boston museum acquired a strange mummy that was discovered on a tiny uncharted Pacific island. The mummy has a look of terror on its shriveled face and is carrying a scroll case with a scroll in some incomprehensible language. In the 1930s the curator of the museum reads from Nameless Cults and begins to figure out who this mummy is. At about the same time a journalist writes a story about the mummy, and all the weirdos on the Pacific Rim who pine for the days of Mu get wind of the mummy's discovery and make a beeline to Beantown to study, worship, or steal the mummy who, they believe, looked upon the god Ghatanothoa and has a memory of this sight stored inside its 174,000-year-old brain. The final third of the story deals with the final fate of the Asian cultists, the museum staff who have to deal with them, and the mummy--let's just say none of these people dies peacefully in his sleep with an easy conscience.

The 20th-century parts of "Out of the Aeons" are just OK; the real magic lies in the paraphrase of the history of K'naa and the story of T'yog, which is like a great sword and sorcery tale set in the perfect setup for an awesome AD&D campaign.

"Out of the Aeons" was later included in the Lovecraft collection Beyond the Wall of Sleep (dig the Clark Ashton Smith sculptures on the cover), August Derleth's anthology The Sleeping and the Dead, and Avon Fantasy Reader #18, edited by famed SF editor Donald Wollheim.

"The Horror in the Burying-Ground" (1933)

"The Horror in the Burying-Ground" (1933)This is the weakest of the five Heald stories, a sort of lampoon of small town hicks. (It always makes me a little uneasy when city sophisticates make fun of the lower classes and small town people. I guess because of the clothes I wore and the way I would carry a volume of Proust or Nabokov around like a talisman, some of the leftist social science grad students I worked with in my Manhattan days didn't know I came from a working class background, and they would frankly express their disgust with "white working-class people" around me. These daughters of college professors, who were following in their parents' footsteps in pursuing a career of leeching off the taxpayers, always made sure to include "white" in their description of the people who aroused their contempt.) "The Horror in the Burying-Ground" has a tedious frame story with lots of characters, and the main drama, a sort of love triangle and premature burial tale, also has too many characters.

If you stop at the general store in the crummy rural town of Stillwater maybe the local goofballs who hang out there will tell you the story of Sophie Sprague, Tom Sprague, Henry Thorndike, and crazy Johnny Dow. Tom was Sophie's brother, and the two lived together on their farm. Tom was a violent drunk who kept men away from his sister, but when he was off on a spree Thorndike would court her. Thorndike was the local undertaker, a med school drop out. Johnny Dow, variously described as "an idiot" and "a half-wit" acted as a sort of assistant or flunky of Thorndike's--Thorndike compensated him by shooting him up with heroin or morphine or something. The garrulous and mentally deficient Dow with his unguarded talk revealed to everybody that Thorndike was always experimenting with new drugs and embalming fluids on cats and dogs and even the local livestock.

|

| Abridged 1965 UK edition of 1944's Sleep No More; it only has 11 stories instead of 20, but they throw in a sexy Dracula lady |

Thorndike didn't do a good job with the dosage, and Tom had some kind of spasm and knocked the syringe needle into Thorndike's own arm, so that the undertaker got a dose of his own medicine. During the comic funeral scene Thorndike collapses and the local doctor pronounces him dead as well, the upshot being, despite the protests of the "half-wit" Dow, that both men are buried alive, and for decades to come, Dow will visit their graves and talk to them.

Gotta give this thing, which is too long, tries and fails to be funny, and lacks the "cosmic" horror we look for in a Lovecraft story as well as any of the suspense or shock we look for in any horror tale, a thumbs down. Despite my denunciation, after its initial publication in Weird Tales along with Kuttner's "The Salem Horror," "The Horror in the Burying-Ground" was included in August Derleth's Sleep No More: Twenty Masterpieces of Horror for the Connoisseur.

**********

Well, we've got one clunker in "The Horror in the Burying-Ground," but "The Horror in the Museum" and "Winged Death" are very good, "Out of the Aeons" has a cool middle section, and "The Stone Man" isn't bad.

In our next episode I temporarily suspend my boycott of the 21st century to read Lovecraftian stories from 2014!

No comments:

Post a Comment