|

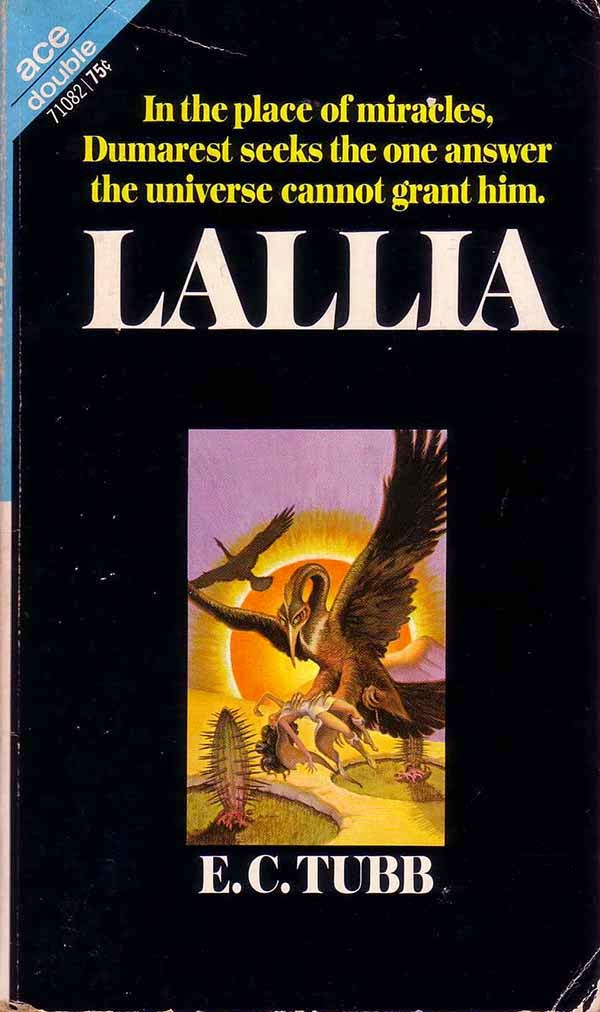

| My copy, front |

"Eutopia" by Poul Anderson

This is one of those stories with alternate universes with alternate histories. Iason Phillipou is a 20th century Greek from a version of Earth in which Alexander the Great lived longer and consolidated his conquests. (As all you history buffs know, in our world Alexander died young and his empire immediately broke up into many squabbling principalities.) Iason's job is to travel between various versions of Earth conducting research; during the course of this story he travels around a North America consisting of many small states, some populated by Europeans and others by native Americans. Having accidentally insulted a potentate of one state, Iason is chased by aircraft while driving a stolen car, then by dogs and horsemen while he runs through a forest. Eventually he finds sanctuary in another principality and gets transported back to his own universe.

Through Iason's homesick musings and conversations with other people, Anderson compares and contrasts three different Earths: our own universe, where the Romans and Christians molded European civilization and whites conquered the New World, leading to Indian civilization being almost entirely wiped out; Iason's Alexandrine world, known as "Eutopia," which is rational, scientific and tolerant (there is no war and in the 20th century the moon and Venus have been terraformed); and the world Iason is exploring, where Christianity collapsed under the weight of Muslim and Viking attacks and European and native societies both thrive in 20th century North America.

"Eutopia" feels "dangerous" early on because Iason blames the Romans and Christians for slowing down scientific progress and creating the culture of intolerance which lead to pollution, totalitarianism, and nuclear warfare in our own world. Iason is positive that his own rational, peaceful, superscientific world is far superior to ours, and to the world he is exploring. But Anderson cleverly pulls a swircheroo on us in the end of the story. One of Iason's colleagues suggests that their world, Eutopia, is spiritually dead because nobody believes anything and because there are no challenges; perhaps to reach his full potential, to really live, man needs the irrational romance of religion and nationalism, the challenges of politics and war. And then in the last line, when Iason has been teleported back to Eutopia, we learn that the "Niki" he has been pining for is "Nikias Demosthenou, most beautiful and enchanting of boys"-- Iason is a pederast! Should this change our view of his society, and his assessment of our own?

"Eutopia" is an entertaining and thought-provoking story. I think its ambiguity (it questions our own Roman/Christian civilization, but is also skeptical of a more rational alternative) is actually more challenging to the reader and "dangerous" than something like Chad Oliver's contribution to Again, Dangerous Visions which I talked about in my last blog post. Oliver's story is one-sided and histrionic, the kind of story hardcore environmentalists might embrace, while Anderson's story has the potential to challenge or even offend almost anybody.

In my post about Oliver I pointed out that I am not the audience for utopian stories or anti-pollution stories. Here I will admit that I absolutely am the audience for a story like "Eutopia" which not only challenges our society, but the very idea of utopia. I also thought "Eutopia" included some memorable images. Iason's homesick memory of a moon that glitters at night with the light of cities reminded me of one of my favorite images from Gene Wolfe's 1980s tetralogy, The Book of the New Sun, in which the moon in the far future has been terraformed and is green because it is covered in forests.

So, bravo to Anderson and to editor Ellison for this one.

|

| ...and back |

This is a pleasant little story. Why do the Roma people, the Gypsies, travel all over the Earth? Because in ancient times space aliens carried away the piece of the Earth that was their homeland, ten thousand square miles of less than a mile deep, to study, the way a doctor might take a slice from a patient or a geologist a chip off a rock to look at under a microscope. The aliens implanted in the minds of the Gypsies an inability to settle down until their land was returned.

In this story the aliens bring back the slice, and people with Roma blood all around the world abandon their businesses and homes and rush to return to their ancestral homeland in Northern India. Then the aliens take another Earth sample, this one including Los Angeles, giving rise to a new Gypsy culture, the Angelenos, also known as the "Automobile Gypsies."

I like this story, it is fun and clever, but I can't see how it is "dangerous." I guess it includes a gentle criticism of car culture and automobile pollution.

Well, dangerous or not, a good story.

This is a humorous tale, perhaps a satire, in which a man battles cars in the arena in exactly the way a matador fights a bull. Set in a future in which people are riding horses again, the cars are robots and perhaps sentient. The story is narrated by a spectator at a particularly dramatic fight.

I've read several Zelazny stories about robot cars; maybe automobiles were one of his interests?

I liked this story, and it succeeded in making me laugh, but it feels a little slight and not very "dangerous." Maybe we are supposed to see it as a criticism of blood sports, or a jocular reminder of the dangers of automobiles? An auto-da-fé was a religious ceremony, an act of penance associated with the punishment of heretics, and perhaps Zelazny is satirizing car culture as a debased religion, and/or suggesting that human beings should be punished for foisting upon the world the automobile, which causes so much pollution and kills however many thousands of people every year in accidents.

"Auto-da-fé" reminded me of Primo Levi's 1976 short story "Gladiators," which I read a few years ago and also is about a spectator at an arena in which a man fights cars, but that story, if memory serves, was very serious.

A good story, probably more "dangerous" than the Lafferty, but not particularly dangerous.

***********

Three good stories from three good writers; you probably know this already, but Dangerous Visions certainly seems like a worthwhile purchase, an anthology full of good stories. All three stories are entertaining, but, perhaps surprisingly, the most "dangerous" one was by that titan of old-school SF, the most conventional writer of the bunch, Poul Anderson.